Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnet 6 “Go from me. Yet I feel that I shall stand”

Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s sonnet 6 is a clever seduction sonnet; as the speaker seems to be giving the suitor every reason to leave her, she is also giving him very good reasons to remain.

Introduction and Text of Sonnet 6 “Go from me. Yet I feel that I shall stand”

Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s sonnet 6 from Sonnets from the Portuguese may be thought of as the seeming reversal of a seduction theme. At first the speaker seems to be dismissing her lover. But as she continues, she shows just how close they already are.

The speaker’s revelation that he will always be with her, even though she has sent him away from the relationship, is bolstered by many instances of intensity that is surely meant to keep the love attracted instead of repelling him.

Sonnet 6 “Go from me. Yet I feel that I shall stand”

Go from me. Yet I feel that I shall stand

Hence forward in thy shadow. Nevermore

Alone upon the threshold of my door

Of individual life, I shall command

The uses of my soul, nor lift my hand

Serenely in the sunshine as before,

Without the sense of that which I forbore—

Thy touch upon the palm. The widest land

Doom takes to part us, leaves thy heart in mine

With pulses that beat double. What I do

And what I dream include thee, as the wine

Must taste of its own grapes. And when I sue

God for myself, He hears that name of thine,

And sees within my eyes the tears of two.

Reading:

Commentary on Sonnet 6 “Go from me. Yet I feel that I shall stand”

This sonnet is a clever seduction sonnet; as the speaker seems to be giving the suitor every reason to leave her, she is also giving him very good reasons that they should remain together.

She is always trying to convince herself more than her suitor, for she already intuits that he believes their union is meant to be. He knows the depth of his love for her. But she must convince herself that that depth is genuine.

First Quatrain: No Equal Partnership

Go from me. Yet I feel that I shall stand

Hence forward in thy shadow. Nevermore

Alone upon the threshold of my door

Of individual life, I shall command

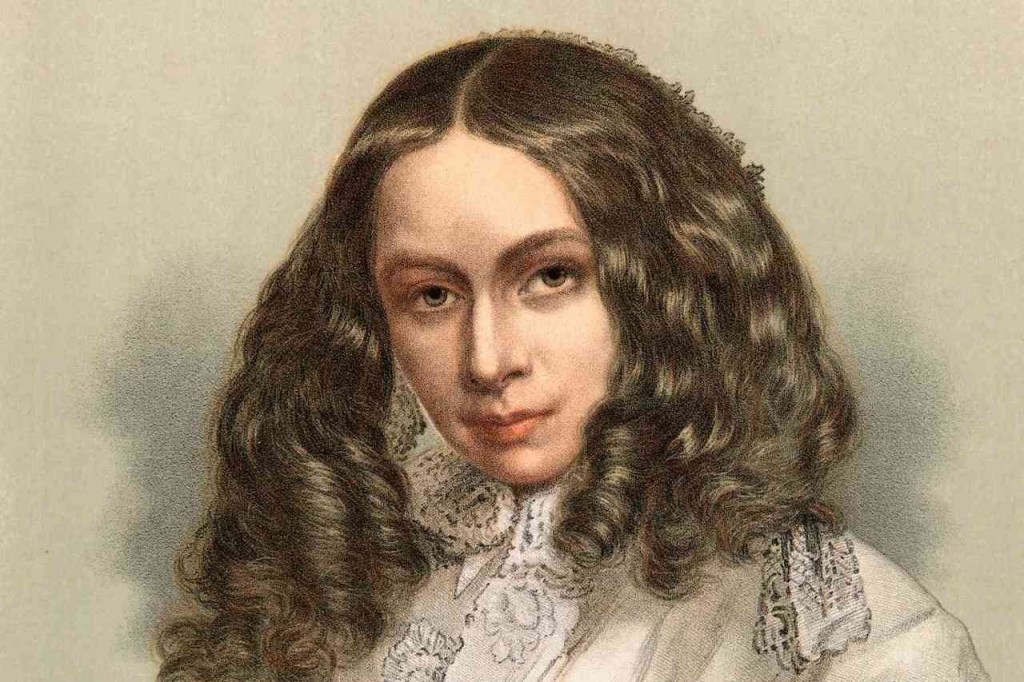

In Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s sonnet 6 from Sonnets from the Portuguese, the speaker is commanding her beloved to leave her. As she has protested in earlier sonnets, she does not believe she is equal to his stature, and such a match could not withstand the scrutiny of their class society.

But the clever speaker also hastens to add that his spirit will always remain with her, and she will henceforth be “[n]evermore / Alone upon the threshold of my door / Of individual life.”

That the speaker once met and touched one so esteemed will continue to play as a presence in her mind and heart. She is grateful for the opportunity just to have briefly known him, but she cannot presume that they could have a permanent relationship.

Second Quatrain: Never to Forget

The uses of my soul, nor lift my hand

Serenely in the sunshine as before,

Without the sense of that which I forbore—

Thy touch upon the palm. The widest land

The speaker continues the thought that her beloved’s presence will remain with her as she commands her own soul’s activities. Even as she may “lift [her] hand” and view it in the sunlight, she will be reminded that a wonderful man once held it and touched “the palm.”

The speaker has married herself so securely to her beloved’s essence that she avows that she cannot henceforth be without him. As she attempts to convince herself that such a life will suffice, she also attempts to convince her beloved that they are already inseparable.

First Tercet: Metaphysically Together Always

Doom takes to part us, leaves thy heart in mine

With pulses that beat double. What I do

And what I dream include thee, as the wine

No matter how far apart the two may travel, no matter how many miles the landscape “doom[s]” them to separation, their two hearts will forever beat together, as “pulses that beat double.”

Everything she does in future will include him, and in her every dream, he will appear. She is binding them together on the metaphysical level, where such bonds can never be broken, as they can on the physical level of being.

Second Tercet: Prayers That Include Her Beloved

Must taste of its own grapes. And when I sue

God for myself, He hears that name of thine,

And sees within my eyes the tears of two.

They will be a union as close as grapes and wine: “as the wine / / Must taste of its own grapes.” Her juxtaposition of wine and tears becomes symbolic of their liquid love, running together as any stream to the sea.

And when she supplicates to God, she will always include the name of her beloved. She will never be able to pray only for herself but will always pray for him as well. And when the speaker sheds tears before God, she will be shedding “the tears of two.” In her spiritual life, the two are already bound together.

Her life will be so bound together with her beloved that there is no need for him to remain with her physically, and she has given reasons that he should depart and not feel any pangs of sorrow for her.

In fact, he will not be leaving her if they are so closely united already. They can never be parted despite any measure of physical distance. While the speaker seems to be giving the suitor every opportunity to leave her by exaggerating their union, her pleadings also reveal that she is giving him every reason to remain with her.

If they are already as close and wine and grapes, and she adores him so greatly as to continue to remember that he touched her palm, such strong love and adoration would be difficult to turn down.

Despite the class differences that superficially separate them, the speaker must somehow come to understand that their parting is not an option. The metaphysical level of being must be explored for the sake of reality.