Note on Term Usage: Before the late 1980s in the United States, the terms “Negro,” “colored,” and “black” were accepted widely in American English parlance. While the term “Negro” had started to lose it popularity in the 1960s, it wasn’t until 1988 that the Reverend Jesse Jackson began insisting that Americans adopt the phrase “African American.” The earlier more accurate terms were the custom at the time that Langston Hughes was writing.

Langston Hughes’ “Goodbye, Christ”

Langston Hughes wrote “Goodbye, Christ” in 1931. It was published in a statist publication called “The Negro Worker” in 1932, but Hughes later withdrew it from publication.

Introduction with Text of “Goodbye, Christ”

Nine years after the publication of Langston Hughes’ “Goodbye, Christ,” on January 1, 1941, the poet was scheduled to deliver a talk about Negro folk songs at the Pasadena Hotel. Members of Aimee Semple McPherson’s Temple of the Four Square Gospel picketed the hotel with a sound truck playing “God Bless America.”

Likely those members of the McPherson temple became aware of the poem because McPherson is mentioned in it. The protestors passed out copies of Hughes’ poem, “Goodbye, Christ,” even though they had not secured permission to copy and distribute it.

A few weeks later, The Saturday Evening Post, heretofore no friend to black writers, also mentioned in the poem, also printed the poem without permission. The poem had received little attention until these two events.

But Hughes had been criticized for his “revolutionary” writings and apparent sympathy for the Soviet form of government. On March 24, 1953, Hughes was called to testify before the Joseph McCarthy’s Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations.

Goodbye, Christ

Listen, Christ,

You did alright in your day, I reckon-

But that day’s gone now.

They ghosted you up a swell story, too,

Called it Bible-

But it’s dead now,

The popes and the preachers’ve

Made too much money from it.

They’ve sold you to too many

Kings, generals, robbers, and killers-

Even to the Tzar and the Cossacks,

Even to Rockefeller’s Church,

Even to THE SATURDAY EVENING POST.

You ain’t no good no more.

They’ve pawned you

Till you’ve done wore out.

Goodbye,

Christ Jesus Lord God Jehova,

Beat it on away from here now.

Make way for a new guy with no religion at all-

A real guy named

Marx Communist Lenin Peasant Stalin Worker ME-

I said, ME!

Go ahead on now,

You’re getting in the way of things, Lord.

And please take Saint Gandhi with you when you go,

And Saint Pope Pius,

And Saint Aimee McPherson,

And big black Saint Becton

Of the Consecrated Dime.

And step on the gas, Christ!

Move!

Don’t be so slow about movin?

The world is mine from now on-

And nobody’s gonna sell ME

To a king, or a general,

Or a millionaire.

Commentary on “Goodbye, Christ”

Langston Hughes’ poem “Goodbye, Christ” is a dramatic monologue. The speaker is addressing Christ, telling him to leave because He is no longer wanted. The speaker is employing irony and sarcasm to express his distrust and disapproval of the many people, including the clergy, who have used religion only for financial gain.

Serving God or Mammon

In the first verse paragraph (versagraph), the speaker explains to Christ that things are different now from the way they were back in Christ’s day; the speaker figures that back then Christ’s presence might have been appreciated, but now “[t]he popes and the preachers’ve / Made too much money from [your story].”

And that complaint is addressed in the poem that certain individuals and organizations have used the name of Christ to make money: “They’ve pawned you / Till you’ve done wore out.”

The speaker makes it clear that it is not only Christianity that has been desecrated, for he also includes Hinduism when he tells Christ “please take Saint Gandhi with you when you go.” It is not only white people like McPherson, but also “big black Saint Becton,” a charlatan preacher Hughes mentions in his autobiography, The Big Sea.

Hughes is, in no way, repudiating Jesus Christ and true religion. He is, however, excoriating those whom he considers charlatans, who have profited only financially without highlighting the true meaning of Christ’s (or other religions’) teachings.

Langston Hughes on “Goodbye, Christ”

In editor Faith Berry’s Good Morning Revolution: Uncollected Writing of Langston Hughes, Berry brings together a large collection of writings for which Hughes did not seek wide publication. Some of his early politically statist-leaning poems, which had appeared in obscure publications, managed to circulate, and Hughes was labeled a Communist, which he always denied in his speeches.

About “Goodbye, Christ,” Hughes has explained that he had withdrawn the poem from publication, but it had appeared without his permission and knowledge. Hughes also insisted that he had never been a member of the Communist Party. He went so far as to say he wished Christ would return to save humanity, which was in dire need of saving, as it could not save itself.

Earlier in his immaturity, Hughes had believed that the communist form of government would be more favorable to black people, but he became aware that his VIP treatment in Russia was a ruse, calculated to make people of color think that communism was friendlier to them than capitalism while ultimately hoodwinking them just as the Democratic Party did later on in the century. (Also see Carol Swain’s “The Inconvenient Truth about the Democratic Party”)

In his senate committee testimony on March 24, 1953, Hughes makes his political inclinations clear that he had never read any book on the theory of socialism and communism. Also, he had not delved into the stances of the Republican and Democrat parties in the United States.

Hughes claimed that his interest in politics was prompted solely by his emotion. Only through his own emotions had he glanced at what politics might have to offer him in figuring out personal issues with society. So in “Goodbye, Christ,” the following versagraph likely defines the poet’s attitude at its emotional depths:

Goodbye,

Christ Jesus Lord God Jehova,

Beat it on away from here now.

Make way for a new guy with no religion at all—

-A real guy named

Marx Communist Lenin Peasant Stalin Worker ME—

I said, ME!

Hughes spent a year in Russia and came back to America writing glowing reports of the wonderful equalities enjoyed by all Russians, which many critics wrongly interpreted to indicate that Hughes became a communist. On January 1, 1941, Hughes wrote the following clear-eyed explanation that should once and for all put to rest the notion that his poem was meant to serve blasphemous purposes:

“Goodbye, Christ” does not represent my personal viewpoint. It was long ago withdrawn from circulation and has been reprinted recently without my knowledge or consent. I would not now use such a technique of approach since I feel that a mere poem is quite unable to compete in the power to shock with the current horrors of war and oppression abroad in the greater part of the world.

I have never been a member of the Communist party. Furthermore, I have come to believe that no system of ethics, religion, morals, or government is of permanent value which does not first start with and change the human heart. Mortal frailty, greed, and error know no boundary lines.

The explosives of war do not care whose hand fashions them. Certainly, both Marxists and Christians can be cruel. Would that Christ came back to save us all. We do not know how to save ourselves. (my emphasis added) —from Good Morning Revolution: Uncollected Writing of Langston Hughes, page 149.

The Importance of Understanding the Irony in “Goodbye, Christ”

While it may be difficult for devout Christians, who love Christ and his teachings, to read such seemingly blasphemous writing, it is important to distinguish between the literal and the figurative: Hughes’ “Goodbye, Christ” must be read through the lens of irony and sarcasm, and realized as a statement against the financial usurpation of religion, and not a repudiation of Christ and the great spiritual masters of all religions.

It should be remembered that Hughes’ seemingly blasphemous poem simply creates a character who was speaking ironically, even sarcastically, in order to call out the actual despicable blasphemers who desecrate true religion with duplicity and chicanery.

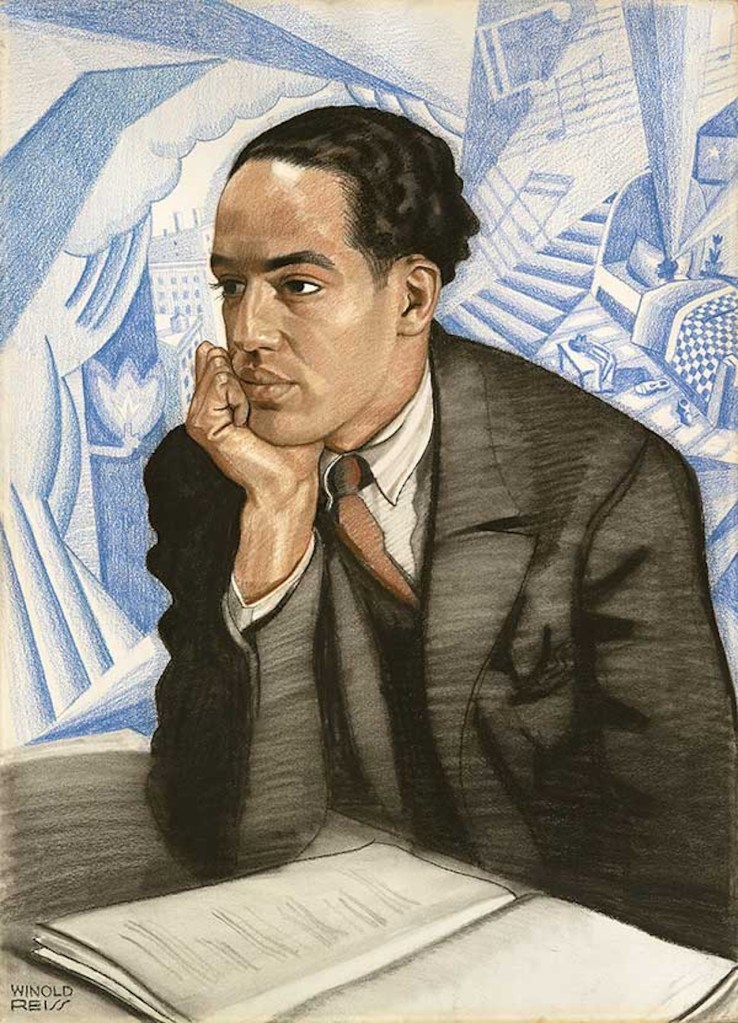

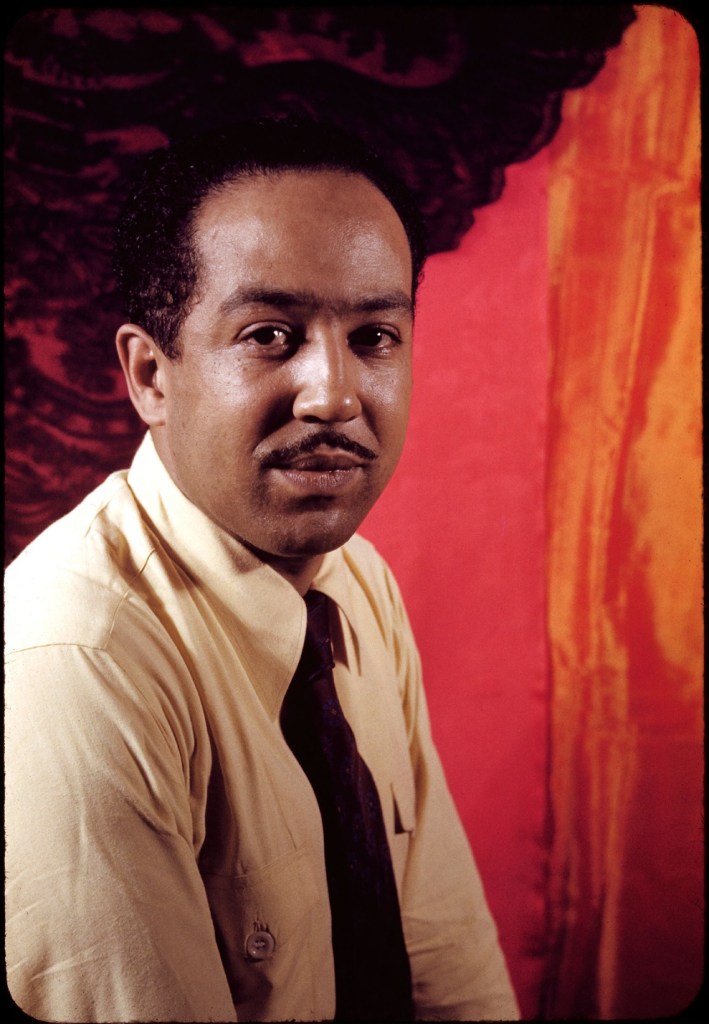

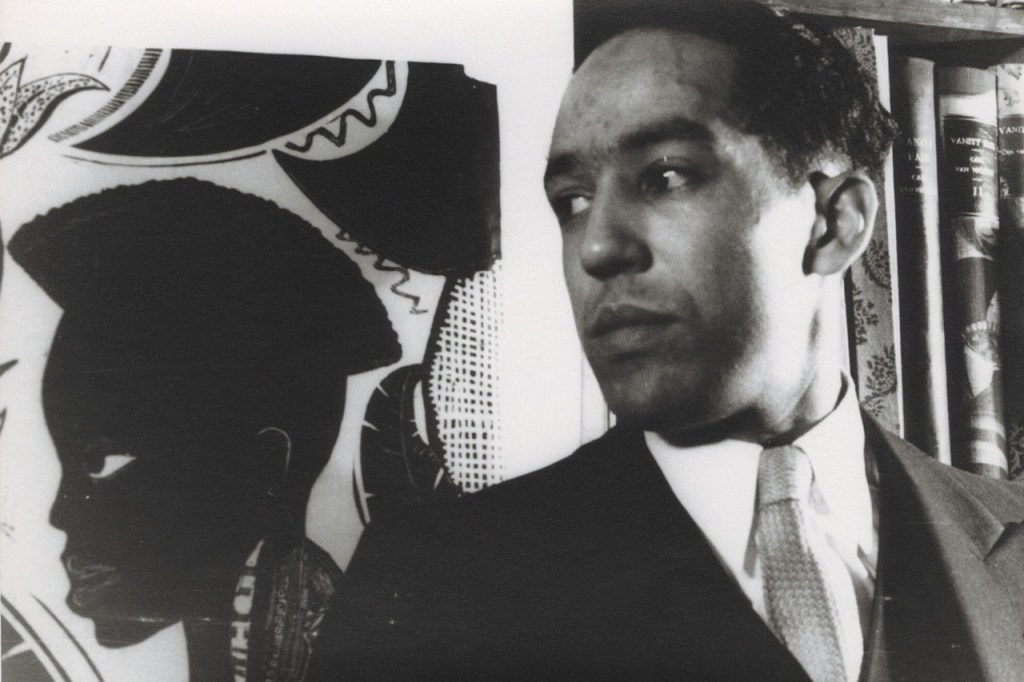

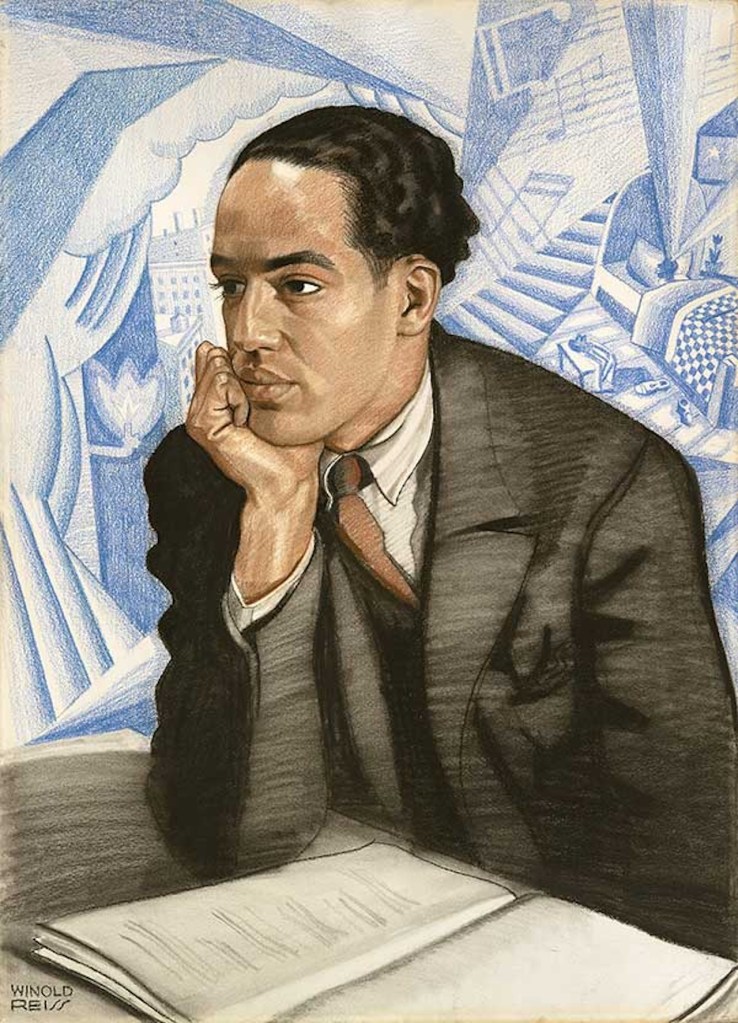

Image: Ink Drawing of Langston Hughes– Ink Portrait – Fabrizio Cassett