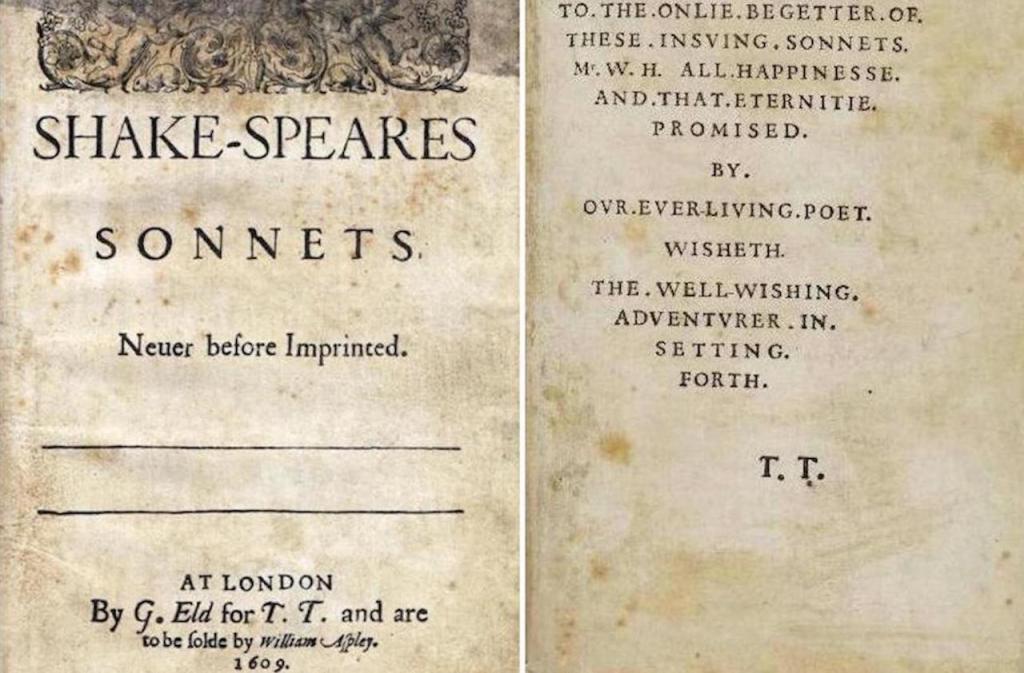

Image: Shake-speares Sonnets Hank Whittemore’s Shakespeare Blog

Introduction to the Shakespeare 154-Sonnet Sequence

The Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence offers a study of the mind of the poet. The first 17 have a speaker persuading a young man to marry and produce lovely offspring. Sonnets 18–126 address issues relating to talent and art creation. The final 28 explore and lament an unhealthy romance.

Commentaries on the Shakespeare 154-Sonnet Sequence

My Shakespeare sonnet commentaries are being offered to assist beginning poetry readers and students in understanding and appreciating the Shakespeare sonnet sequence. Because I argue alongside the Oxfordians regarding the identity of “William Shakespeare,” some of my commentaries on the sonnets include information related to the Shakespeare writer as Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford.

However, consideration of the poet’s biography remains only one small factor in understanding and appreciating his art, especially the sonnets. The sonnets’ messages are what they are regardless of the biography of who wrote them. The “Shakespeare” identity is not the only issue with which I take exception to traditional Shakespeare studies.

I do not agree with the traditional view that sonnets 18–126 focus on a “fair youth.” I will show that in most of that group of sonnets there is no person at all, much less a “fair youth” or young man.

I assert instead that those sonnets put on display the theme of the poet’s relationships with his muse, with his own heart and mind, with his art—including his doubts and fears regarding his ability to maintain and perfect his writing abilities.

The Sonnet Sequence

Some online Shakespeare sonnet enthusiasts have divided the 154 sequence into two thematic categories: “The Fair Youth Sonnets” (1–126) and “The Dark Lady Sonnets” (127–154). Such a categorization remains problematic because there is a distinct change of subject matter from the first section 1-17 to the second 18–126.

In the first section of sonnets 1–17, the speaker is clearly imploring a young man to marry and procreate; in the second section 18–126, the speaker remains highly contemplative as he muses upon his considerable talent.

The only feature that the first two categories have in common would be a “fair youth”; however, it is a misinterpretation that assigns a “fair youth” to sonnets 18–126. As I mentioned above, in most of that group of sonnets there is no person at all.

In opposition to the two category theory, a number of scholars and critics of Elizabethan literary studies have categorized the Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence into three thematic groups:

1. Marriage Sonnets: 1–17 (17 total)

2. Fair Youth Sonnets: 18–126 (109 total)

3. Dark Lady Sonnets: 127–154 (28 total)

Sonnets 1–17: The Marriage Sonnets

The group labeled the “Marriage Sonnets” stars a speaker, attempting to persuade a young man to marry and produce beautiful children. Oxfordians, who hold that the actual Shakespeare writer was Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, suggest that the young man is probably Henry Wriothesley, the third Earl of Southhampton and that the speaker of sonnets 1–17 is striving to convince the young earl to marry Elizabeth de Vere, the eldest daughter of Edward de Vere.

Sonnets 18–126: The Fair Youth Sonnets

By tradition, the “Faith Youth Sonnets” are interpreted as further entreaties to a young man. However, there is no young man in these sonnets; there are no persons at all in that group of sonnets. Even though sonnets 108 and 126 do address a “sweet boy” or “lovely boy,” they remain problematic and are likely miscategorized.

The Category “Muse Sonnets” Replaces the “Fair Youth Sonnets”

Instead of speaking directly to a young man, as the “Marriage Sonnets” quite obviously do, the speaker in sonnets 17–126 is musing on, examining, and exploring issues of writing, thinking, and making poetry. In some of the sonnets, the speaker addresses his muse, and in others, his talent, and in still others, he is speaking directly to the sonnet itself.

The speaker in sonnet after sonnet is exploring the entire territory of his talent, his dedication to writing and the power of his heart and soul. He even goes into battle with the bane of a writer’s existence—periods of low inspiration for creating. He also struggles with the ennui and dryness that the writing experience undergoes.

The result of my understanding and interpretation of this “Fair Youth” category offers a very different line of thinking from the traditionally received position of this issue. I have, therefore, relabeled the category the “Muse Sonnets”—replacing the traditional “Fair Youth Sonnets.”

The motive for the continued labeling the bulk of the Shakespeare sonnets “Fair Youth” likely rests with the social justice movement in rehabilitation of the same-sex orientation. Finding evidence of homosexuality in long respected writers and artists has become a cottage industry, especially for the statist-leaning, higher education system.

While a number of academics have bloviated in the direction of finding of Shakespeare was “gay,” others have convincingly debunked the notion. Interestingly, those who favor the gay Shakespeare use the “Fair Youth” sonnets as their main supporting evidence.

Also interestingly, the debunking of the notion of same-sex orientation in “Shakespeare” would be much easier if those critics assumed the real “Shakespeare” to be Edward de Vere, whose biography is known and well documented, while that of the traditional “Shakespeare,” Gulielmus Shakspere of Stratford, remains rather thin and sketchy.

Sonnets 127–154: The Dark Lady Sonnets

The “Dark Lady” sonnets offer an exploration of an adulterous relationship with a woman who possesses an unsavory character. The term “dark” is describing the woman’s shady character flaws, rather than the shade or hue of her complexion.

Six Problematic Sonnets: 108, 126, 99, 130, 153, 154

Sonnets 108 and 126 offer a different kind of categorization issue. Most of the “Muse Sonnets” are speaking to writing issues, wherein the speaker examines his talent, dedication, and other issues relating to his artist skills. There are no other human beings in most of these muse sonnets.

However, sonnets 108 and 126 do address a young man, calling him “sweet boy” and “lovely boy.” And then poem 126 is not technically a “sonnet.” It plays out in six rimed couplets, not the traditional sonnet form with three quatrains and one couplet.

The possibility remains that sonnets 108 and 126 have helped cause the misnaming of this group of sonnets as the “Fair Youth Sonnets.” Those poems should logically reside with the “Marriage Sonnets,” which do address a young man.

Sonnets 108 and 126 could also be responsible for some scholars categorizing the sonnets into two groups, instead of three—combining the “Marriage Sonnets” with the “Fair Youth Sonnets” and naming them the “Young Man Sonnets.”

However, the two category alternative remains flawed because the bulk of the “Fair Youth Sonnets” do not address a young man, nor do they address any person, except on occasion as the speaker addresses himself.

Sonnet 99 contains 15 lines, instead of the traditional sonnet form with 14 lines. The first quatrain expands to a cinquain, converting its rime scheme from ABAB to ABABA. The rest of the sonnet continues traditionally, following the rime, rhythm, and function of the traditional sonnet.

Although sonnet 130 “My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun” is grouped with the “Dark Lady” subsequence, it seems to prove an anomaly because in many of the others in this group the lady does not merit such positive effusions as offered in the speaker’s claim that his “love” for her is rare.

The “Dark Lady” sonnets explore the negative results of unchecked lust, while the execution of sonnet 130 takes for its purpose the criticism of hyperbolic displays that idealize cosmetic beauty. This speaker remains consistent in his striving for truth as well as his striving for beauty.

The Two Final Sonnets

Sonnets 153 and 154 are problematic also, at least to some extent. Although they are categorized thematically with the “Dark Lady Sonnets,” they function a bit differently from most of the poems in that thematic group. Sonnet 154 simply features a paraphrase of sonnet 153, dramatizing identical messaging—the complaint of unrequited love.

Those two final sonnets then decorate that complaint with the tinsel of mythological allusion. The speaker alludes to the force of Cupid, the Roman god of love and the power of the goddess Diana.

The speaker thereby maintains a secure distance from his feelings. He possibly hopes such distancing may liberate him from the oppression of his lust and then re-establish for him the harmonious balance of mind and heart.

In the majority of the “Dark Lady Sonnets,” the speaker has continued to offer a monologue to the woman, making it clear that he intends for her to hear about that which he is complaining.

Finally, in the two concluding sonnets, the speaker is no longer addressing the dark lady. He does mention her, but instead of speaking directly to her, he is declaiming about her. He is employing this strategy to engage and demonstrate that he is withdrawing from the woman and her unsavory mannerisms.

The conclusion of this sequence seems to be dramatizing the fact that the speaker has become disillusioned by and weary from his battle for this disagreeable woman’s love, affection, and respect.

The speaker concludes that he is determined to fashion a high-principled, classic, dramatic statement to put an end to this ill-omened relationship, with an unmistakeable pronouncement that he is finished, it is over, he is through.

Image: Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford-The Writer of the Shakespeare Canon

🕉

You are welcome to join me on the following social media:

TruthSocial, Locals, Gettr, X, Bluesky, Facebook, Pinterest

🕉

Share