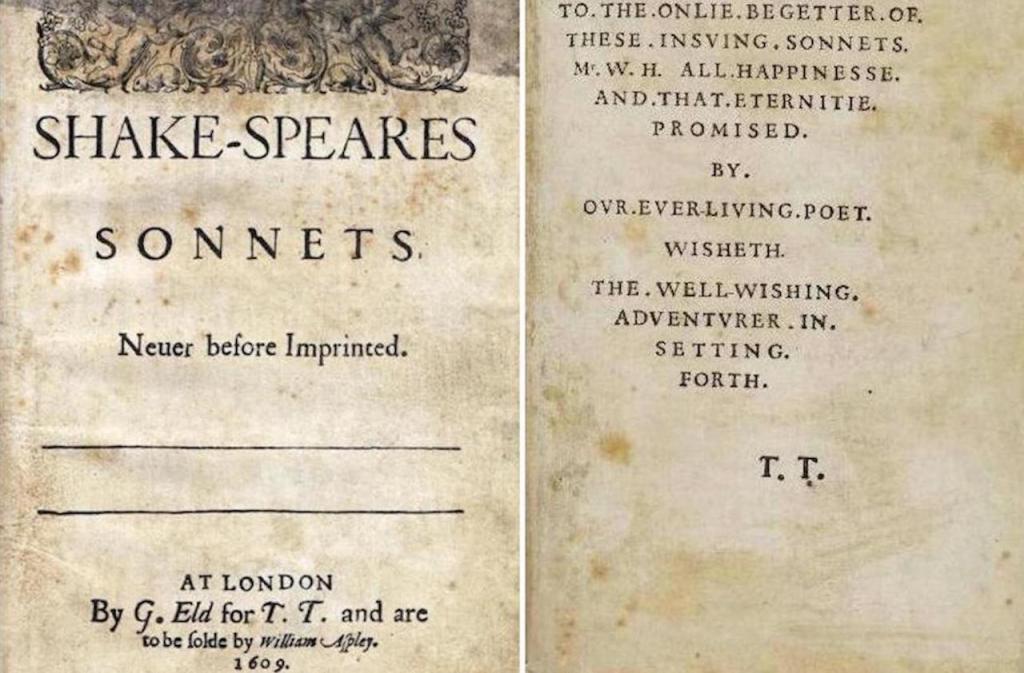

Image: Shake-speares Sonnets Hank Whittemore’s Shakespeare Blog

The Marriage Sonnets

From the classic 154 Shakespeare sonnet sequence, the “Marriage Sonnets” 1—17 features a speaker, attempting to persuade a young man to marry and produces beautiful children. Oxfordians, who hold that the actual Shakespeare writer was Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, suggest that the young man is probably Henry Wriothesley, the third Earl of Southhampton and that the speaker of sonnets 1–17 is striving to convince the young earl to marry Elizabeth de Vere, the eldest daughter of Edward de Vere.

Shakespeare Sonnet 1 “From fairest creatures we desire increase”

The first sonnet “From fairest creatures we desire increase” focuses on persuading a young man to marry and procreate beautiful offspring; the speaker continues that engagement in sonnets 1–17.

Introduction and Text of Sonnet 1 “From fairest creatures we desire increase”

While the Shakespeare canon is most noted for its plays, including Hamlet, Macbeth, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Taming of the Shew, Romeo and Juliet, and many others, the Shakespeare writer’s literary masterpieces also feature a sequence of 154 masterfully crafted sonnets.

Despite the wide-spread tendency to categorize the sonnets thematically into two groups, the first 126 focusing on a young man and the remainder focusing on an illicit affair with “dark lady,” the actual thematic structure supports three distinct groups:

- The Marriage Sonnets (often miscategorized in “Fair Youth”): 1–17

- The Muse Sonnets (often mistaken as “Fair Youth Sonnets”): 18–126

- The Dark Lady Sonnets: 127–154

The first group—The Marriage Sonnets 1–17—clearly addresses a young man, as the speaker pleads with him to marry and produce beautiful children, who will look like the young man and continue his legacy of well-pleasing features. This group is often merged with the second and labeled “The Fair Youth Sonnets.”

The second group—The Muse Sonnets—mistakenly thought to be addressing the same young man but for a different purpose focuses on the theme of creativity and the place of the muse in the creative process. Because no “fair youth” or any other person appears in the bulk of that thematic group, 18–126, I have relabeled that group to more accurately reflect its theme.

Instead of addressing a young man or any other person, the speaker in “The Muse Sonnets” is speaking variously to his muse, to his talent, to his soul, and even at times to the sonnets themselves.

Sonnet 1 “From fairest creatures we desire increase” resides within the thematic category known as “The Marriage Sonnets,” containing sonnets 1–17. The speaker in “The Marriage Sonnets” is pursuing his purpose with dramatic flair and creativity. He is striving to convince a young man that the latter should marry and produce lovely offspring.

The speaker engages many different strategies in his attempt to persuade the young man to marry, appealing sometimes to his vanity and sometimes to his sense of duty. The creativity of the speaker secures each sonnet’s drama as the sequence offers entertainment as well as enlightenment in poetry creation.

Sonnet 1 “From fairest creatures we desire increase”

From fairest creatures we desire increase

That thereby beauty’s rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease,

His tender heir might bear his memory:

But thou contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed’st thy light’s flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel.

Thou that art now the world’s fresh ornament

And only herald to the gaudy spring,

Within thine own bud buriest thy content,

And, tender churl, mak’st waste in niggarding.

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 1 “From fairest creatures we desire increase”

The speaker begins to ply his persuasive wiles on the young man to marry, conceive, and produce lovely offspring. In this opening sonnet, the speaker is informing the young man that nature itself as well as humanity possess the innate wish to have beautiful people propagate their kind.

First Quatrain: The Desire for Continued Beauty

From fairest creatures we desire increase

That thereby beauty’s rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease,

His tender heir might bear his memory:

The speaker makes the bold claim that nature plus humanity—an entity that the speaker conflates into “we”—possess hopes and wishes that beautiful people of pleasing demeanor fill the world with pleasing specimens after their own kind.

The speaker, likening the young man’s loveliness to a “rose,” is opining that this young man, whom he is addressing, shines forth all those proper physical qualities that need to be replicated.

The speaker thus is taking up a campaign to nudge this beautiful young specimen to marry and produce children that will be as beautiful as the young man is. As the speaker compares the young man’s loveliness to a rose, he strives to persuade the young man that also just like the beauty of the rose, his beauty will wither and die.

However, if the young man will simply accept and follow this more experienced, older man’s advice, he will allow his beauty to be passed on to a new generation, and in place of “by time decrease,” the young man will cause the beauty of the “fairest” kind to increase in the world. If the young man will cause lovely children, who resemble him to be born and inhabit the planet, he will be giving nature and humanity what it most desires.

Second Quatrain: A Selfish Young Man

But thou contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed’st thy light’s flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel.

As the clever speaker continues his persuasion, he then chides the young man, accusing him of being selfish. His stingy ways bespeak an ill-formed character, who wishes to bask in his own self adulation. He berates the young man for desiring to look only at his own beautiful features, such as his “bright eyes.”

The speaker finds it inappropriate that the young man simply continues to delight in his own self-esteem, increasing his own beauty while he continues to remain stingy in passing it on to others.

The speaker then engages in some exaggeration, implying that the young man’s conceited ways are starving the world. They are bringing on “a famine” even in the midst of the youngster’s “abundance”—a plenteous supply that he should be willing to share.

If, instead of remaining selfish, the young man will marry, he can yield forth children, who will present that same loveliness to the world that he already has done. The speaker tries to convince the young man that he is in fact only impeding his own interests by his selfish desire to retain his beautiful qualities only for himself.

The speaker has affected a façade of sorrow to implore the young man to believe that he has become his own worst enemy; ultimately, according to the speaker, the young man is just being unkind to his own “sweet self.” The speaker has no compunction about employing flattery and cunning to fulfill his ultimate purpose.

Third Quatrain: Appeal to Vanity

Thou that art now the world’s fresh ornament

And only herald to the gaudy spring,

Within thine own bud buriest thy content,

And, tender churl, mak’st waste in niggarding.

The speaker seems convinced that accusations of selfishness may be a winning strategy in appealing to the young man’s sense of duty; thus he pulls at the strings of his leanings toward vanity.

Because the young man is only one individual, he will remain only one—and then within himself “bur[y] his content”—if he remains unmarried and fails to spring off lovely, pleasing children. The speaker addresses the young man as “tender churl.” Now, he is nearly begging the young man to cease wasting his time and energy by focusing so selfishly only on himself.

Because the young man’s qualities are so valuable, worth so much more than simple temporary beauty, he must correct the possible loss of those qualities to the world by reproducing more like himself. The young man’s following the older man’s advice would keep a rather bad situation from occurring.

The Couplet: Usurping a World Starving for Beauty

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee.

Finally, speaker concludes his entreaty, by summing up his complaint in a rather blunt manner. Again, he wishes to make the young man believe that his failure to marry and reproduce makes him a usurper of the world’s resources.

According to the speaker’s claims, possessing beauty, loveliness, charm, and all forms of pleasing qualities places on the possessor the duty to replenish the world with those same qualities. The young man should marry and produce children, not only for his own sense of immortality but for sake of society—nature and humanity—that desires such increase.

If, however, this young man continues to reject the counsel of the speaker, he will not only swindle the world, but he will also shortchange himself and discover himself alone facing nothing but “the grave.”

Shakespeare Sonnet 2 “When forty winters shall besiege thy brow”

Shakespeare sonnet 2 from the “Marriage Sonnets” finds the speaker again begging the young man to marry and spring off lovely children, before he becomes too old and decrepit to achieve that goal, one that the speaker insists is of utmost importance for the young man and society.

Introduction with Text of Sonnet 2 “When forty winters shall besiege thy brow”

In the second installment of the “Marriage Sonnets” from the Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence, the speaker continues his attempt to convince the young man to take a wife and add to the next generation his own beautiful children. The speaker admonishes the young man to act before he begins his descent into old age, wherein he will lose his youthful vitality and his physical beauty.

This clever, creative speaker will continue to concoct many dramatic arguments as he strives to persuade this young man that his life will be much happier if he will only accept the older man’s counsel regarding marriage and family creation.

This speaker will often be appealing to the young man’s vanity as well as his sense of duty. His choice of persuasive tactics offers a clue about the speaker’s own relationship with those qualities.

Sonnet 2 “When forty winters shall besiege thy brow”

When forty winters shall besiege thy brow

And dig deep trenches in thy beauty’s field,

Thy youth’s proud livery, so gaz’d on now,

Will be a tatter’d weed, of small worth held:

Then being ask’d, where all thy beauty lies,

Where all the treasure of thy lusty days,

To say, within thine own deep-sunken eyes,

Were an all-eating shame and thriftless praise.

How much more praise deserv’d thy beauty’s use,

If thou couldst answer ‘This fair child of mine

Shall sum my count, and make my old excuse,’

Proving his beauty by succession thine!

This were to be new made when thou art old,

And see thy blood warm when thou feel’st it cold.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary Shakespeare Sonnet 2 “When forty winters shall besiege thy brow”

The speaker in Shakespeare sonnet 2 continues to urge the young man to marry and procreate before he grows too old and decrepit. The speaker is adamant that the young man pass on his pleasing qualities to a new generation.

First Quatrain: Old Age

When forty winters shall besiege thy brow

And dig deep trenches in thy beauty’s field,

Thy youth’s proud livery, so gaz’d on now,

Will be a tatter’d weed, of small worth held:

A man’s life expectancy in Britain during the late 16th and early 17th centuries was about fifty-five years; thus, at the age of forty, an individual was considered old. By employing a metaphor that turns the young man’s “brow” into a plowed cornfield, the speaker is offering a disturbing image of a wrinkled old face that resembles a plowed cornfield with “deep trenches.”

The speaker hopes to use this unsightly spectacle to convince the young man that time is flying. He is aware that the young man, as a target of his pleading, has shown considerable pride in his youthful, handsome appearance.

Thus in reminding the young man that one day in future his handsome, blemish-free, unlined face will be relegated to a “tatter’d weed,” the speaker hopes to enhance the points of his argument. Such a weed face will be worthless in trying to attract a bride.

The sly nature of this speaker continues to emerge as he attempts to engage the young man with his clever rhetorical flourishes. The speaker is continuing to appeal to the young man, focusing on qualities that he feels are most vulnerable to the speaker’s argument and persuasion.

The speaker’s audience may likely be guessing just what the speaker wants to achieve for himself by having the young man give in to his persuasion. At first glance, it seems that the speaker has nothing special to gain from having the young man follow his advice, except perhaps the pleasure of knowing he had the ability to persuade.

Second Quatrain: Treasures Stashed in a Withering Face

Then being ask’d, where all thy beauty lies,

Where all the treasure of thy lusty days,

To say, within thine own deep-sunken eyes,

Were an all-eating shame and thriftless praise.

The speaker now warns the young fellow that if he continues to remain without an heir to all of his admirable qualities, the young man will have to reap the displeasure of having his beautiful, natural treasures socked away in a withering, old, ugly face.

The young fellow’s reason for pride in his handsome countenance will stop dead in its tracks without an heir to keep on display that beautiful face. The speaker simulates frustration that the young man remains so selfish as he steals from the world the benefits of the beauty that the young man has to offer.

Because he is refusing to pass on those favorable qualities for the benefit of society and even the culture, the insolent youth is portrayed as callous and self-absorbed—qualities that the speaker plans to establish in the mind of the young man as dreadfully despicable.

The speaker is demonstrating how deeply he pities the young man for allowing himself to experience a future possessing a deep-trenched face without an heir who could so easily replace his youthful beauty.

Third Quatrain: Continuing the Upbraiding

How much more praise deserv’d thy beauty’s use,

If thou couldst answer ‘This fair child of mine

Shall sum my count, and make my old excuse,’

Proving his beauty by succession thine!

The speaker continues to chide the young man. He dramatizes the contrast that exists between producing a child now to not producing one. If the young man follows the speaker’s counsel and produces lovely children now in his youthful, vital time of life, the young man will be able to take comfort in the fact that he has bestowed on the world a gift that reflects well upon the father.

By offering the world and society the marvelous qualities which will enhance the next generation, the young man is doing his sacred duty, as well as guaranteeing comfort in his golden years. The young man’s beautiful heirs will remain a testament to the future that this father was a handsome, vital man.

If, however, the young fellow continues his obstinate ways of remaining single and childless, he will have to meet the future with a wrinkled old face that resembles a plowed cornfield, and he will possess nothing substantial as he descends into death.

The Couplet: Producing Offspring to Retain Youth

This were to be new made when thou art old,

And see thy blood warm when thou feel’st it cold.

In the couplet, the speaker wraps up his persuasion by stressing that the young man will keep some part of his own youthful beauty by wisely producing lovely offspring who will possess the ability to not only mimic his handsome features but who will also carry on his name.

After the young man unavoidably moves into old age, he will be able to take comfort in the fact that he can experience the joy that splendid children with warm blood coursing through their veins bring to their sire.

The speaker insists that the young man will feel that he has been reinvigorated; the speaker asserts that the young man will be “new made,” simply by seeing his living children. Having those children will mean that he will remain fortified against the inescapable horrible coldness of old age.

Not only does the speaker desire to use the young man’s vanity to convince him, but he also believes that he must create a scenario in which the young man himself will need to be comforted in his old age.

The speaker likely hopes that coldness of old age scenario will strengthen his argumentation. The claim that old age is a period of cold horror is nothing but fabrication.

But the speaker remains desperate to convince the young man that he must marry and procreate. Thus the speaker continues to concoct any likely event in order to gain the upper hand and ultimately win the argument.

Shakespeare Sonnet 3 “Look in thy glass and tell the face thou viewest”

Shakespeare sonnet 3 “Look in thy glass and tell the face thou viewest” from the “Marriage Sonnets” focuses on the young man’s image in the mirror. The speaker is appealing to the young man’s vanity as he continues his persuasive efforts to convince the fellow to marry and have children.

Introduction with Text of Sonnet 3 “Look in thy glass and tell the face thou viewest”

As in sonnets 1 and 2, the speaker in Shakespeare sonnet 3 from the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence is pleading with the young man to marry and produce children in order to pass on his handsome features. The speaker employs many tactics of persuasion as he tries to convince the young man to marry and spring off fine looking progeny.

The speaker’s clever repartee is often amusing as well as entertaining and, as it seems the sly speaker possesses an unlimited number of rhetorical tricks that he so freely employs. The speaker’s ability to argue and persuade is outdone only by his poetic ability to create colorful scenarios of drama.

As this speaker argues, he often attempt to direct his arguments for humanitarian purposes. Fortunately, this speaker never condescends to foolish comparisons but instead keeps his images appropriate as well as fresh.

Sonnet 3 Look in thy glass and tell the face thou viewest

Look in thy glass and tell the face thou viewest

Now is the time that face should form another;

Whose fresh repair if now thou not renewest,

Thou dost beguile the world, unbless some mother.

For where is she so fair whose unear’d womb

Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?

Or who is he so fond will be the tomb,

Of his self-love to stop posterity?

Thou art thy mother’s glass and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime;

So thou through windows of thine age shalt see,

Despite of wrinkles this thy golden time.

But if thou live, remember’d not to be,

Die single and thine image dies with thee.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 3 “Look in thy glass and tell the face thou viewest”

Shakespeare sonnet 3 from the “Marriage Sonnets” concentrates on the young man’s image in the looking-glass, as the speaker exploits the young man vanity for persuasive purposes.

First Quatrain: Checking out the Face in the Mirror

Look in thy glass and tell the face thou viewest

Now is the time that face should form another;

Whose fresh repair if now thou not renewest,

Thou dost beguile the world, unbless some mother.

In the first quatrain, the speaker begins by demanding that the young man carefully peruse his own face in the looking-glass and tell himself, as he does, that the time is now here for him to produce offspring whose faces will be similar to his own.

The speaker wants the young man to believe that if the young fellow does not produce more faces like his own, he will be cheating others, and that includes the mother of those new infants who will inherit his prepossessing qualities. The speaker is playing on the young man’s sympathy by insisting that the young man’s failure to reproduce children will “unbless some mother.”

The young fellow will prevent some mother from experiencing the blessings of giving birth and receiving the glory of offering to the world a new generation. The speaker again puts on display his clever ability to unveil arguments and persuasion that would not only be useful to the young man but would uplift others as well.

Second Quatrain: Questions to Persuade

For where is she so fair whose unear’d womb

Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?

Or who is he so fond will be the tomb,

Of his self-love to stop posterity?

As he so often does, the speaker is again employing questions as he tries to persuade the young man to accept his wise counsel that the young fellow marry and procreate. The speaker insists that his advice is not only quite reasonable, but it is also the only moral and ethical thing to do.

The speaker believes that he must make his argument so well-constructed and accurate that the young fellow cannot possibly disagree with him. The speaker is totally convinced that his own stance on the issue is the only accurate one.

In this second quatrain, the speaker asks the young man whether the latter thinks it could be possible that some young lady exists who would not be open to the chance of serving as the mother of the young man’s beautiful offspring.

The speaker then brings up the issue again of the young man’s hesitance, querying him if there could be any right thinking young fellow so selfish and self-centered that he would keep the next generation from entering life.

Third Quatrain: Same Beauty as His Mother

Thou art thy mother’s glass and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime;

So thou through windows of thine age shalt see,

Despite of wrinkles this thy golden time.

The speaker then begs the young man to think about his relationship to his own mother, reminding him that he has inherited his beauty from his mother. It is because his own mother had the good fortune to have given birth to him—this handsome young man—that she can be put in mind of her own youth, just by looking at her fine looking son.

It should seem quite logical then that after the young man has lived to old age, he will possess the ability to experience his own “April” or “prime,” simply by gazing upon the beautiful, well-formed faces of his own lovely, pleasing offspring.

The speaker’s idea of remaining youthful and full of life are dependent upon the next generation, or in order to remain persuasive, so he would insist the young man also believe. Sometimes individuals will employ an argument simply because the claim may sound feasible, even if the truth of the claim has been yet to be determined.

The Couplet: The Young Man’s Image

But if thou live, remember’d not to be,

Die single and thine image dies with thee.

For the entirety of sonnet 3, the speaker has squarely focused on the young man’s physical appearance, as he appears while peering into a look-glass. The speaker reminds the young fellow of his own youthful appearance and the young man’s mother’s comely looks when she was young. He also points out that the young man now reflects those good looks.

As he focuses directly on image, the speaker hopes to motivate the young man through the strength of the young fellow’s ego. By shining a bright light on the young man’s physical image, the speaker hopes to create a moral sense of duty in the young man. If the young fellow refuses to procreate pleasing children, his beautiful image will die as he dies.

The speaker is appealing to the universal human urge for immortality, as he attempts to persuade the young man that his own immortality depends upon creating images made after his own.

Shakespeare Sonnet 4 “Unthrifty loveliness, why dost thou spend”

Shakespeare sonnet 4 “Unthrifty loveliness, why dost thou spend” from “The Marriage Sonnets” in the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence, finds the speaker engaging a finance metaphor to enhance the drama of his argument.

Introduction with Text of Sonnet 4 “Unthrifty loveliness, why dost thou spend”

The speaker of Shakespeare’s thematic group the “Marriage Sonnets” in the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence is using a different metaphor for each poem as he goes on with his one theme of trying to convince this handsome young man to take a wife and reproduce lovely offspring. The speaker wants the young man to bestow upon his progeny his own pleasing, comely qualities.

Sonnet 4 engages a finance/inheritance metaphor, including issues involving lending and spending as it uses terms such as “spend,” “unthrifty,” “sum,” “bounteous largess,” “executor,” and “audit.”

In the “Marriage Sonnets,” the sly speaker is displaying his desire to have the young man marry and produce pleasant, comely children, as he continues to present his persuasive technique in little sonnet dramas.

Each drama not only attempts to entice the young man, but it also entertains readers and listeners with its brilliant set of metaphors and images. The speaker is as resourceful as he is creative in fashioning his arguments. He often takes advantage of the young man’s sense of responsibility as well as his character flaw of vanity.

Sonnet 4 “Unthrifty loveliness, why dost thou spend”

Unthrifty loveliness, why dost thou spend

Upon thy self thy beauty’s legacy?

Nature’s bequest gives nothing, but doth lend,

And being frank she lends to those are free:

Then, beauteous niggard, why dost thou abuse

The bounteous largess given thee to give?

Profitless usurer, why dost thou use

So great a sum of sums, yet canst not live?

For having traffic with thy self alone,

Thou of thy self thy sweet self dost deceive:

Then how when nature calls thee to be gone,

What acceptable audit canst thou leave?

Thy unused beauty must be tombed with thee,

Which, used, lives th’ executor to be.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 4 “Unthrifty loveliness, why dost thou spend”

This sly speaker presents his little drama employing a useful finance metaphor in this entertaining sonnet drama. He continues to invent colorful scenarios that entertain as well as persuade and convince.

First Quatrain: Why Remain so Selfish?

Unthrifty loveliness, why dost thou spend

Upon thy self thy beauty’s legacy?

Nature’s bequest gives nothing, but doth lend,

And being frank she lends to those are free:

The speaker begins by asking the young man why he continues to spend his pleasing qualities for only his own self-centered pleasures. He then tells the young fellow that nature has not merely placed in him his good qualities for himself alone, but instead, Mother Nature has simply put on loan those qualities to the young man.

Mother Nature has freely allowed the young man to borrow those pleasing features. The speaker asserts that the young man did not have to earn his handsome characteristics from nature. However, the young man does have the duty to pass those fine qualities on to the next generation. Nature has only begun those qualities in him.

Attempting to appeal to the young man’s sense of duty and to his vanity, the speaker creates his money or financial metaphor to engage the young man’s interest and help him better understand the nature of his argument. As a counselor, this speaker feels that he must gather all of his strongest arguments to convince the young man just how serious the situation is.

Second Quatrain: Misusing His Beauty

Then, beauteous niggard, why dost thou abuse

The bounteous largess given thee to give?

Profitless usurer, why dost thou use

So great a sum of sums, yet canst not live?

The speaker chides the young fellow by calling him “beauteous niggard”—selfish lovely one. The speaker insists on knowing why the young man continues to misuse his “bounteous largess.” Attempting to shame the young fellow by claiming that he is misusing his fine qualities, the speaker thinks he can motivate the young man to do as the speaker feels his should.

The speaker has clearly delineated his motives and intentions in the three opening sonnets: that he is in the progress of convincing the young man to take a wife and produces offspring. Thus the speaker can now permit his metaphor to engage without even naming the exact terms involved, such as marrying and reproducing.

The speaker then again is accusing the young fellow of misbehaving as would a “Profitless usurer,” relying on the finance metaphor. The speaker continues to upbraid the young fellow for storing up his wealth of pleasing features, while instead he should be employing them for the greater good of himself and for the world.

The young man’s failure to employ his God-given gifts properly is rendered even worse because he cannot hold on to those gifts forever. The speaker continues to push the notion of the brevity of the span of life as he attempts to impress upon the young man that the situation is quite urgent.

Third Quatrain: Selfishness

For having traffic with thy self alone,

Thou of thy self thy sweet self dost deceive:

Then how when nature calls thee to be gone,

What acceptable audit canst thou leave?

In the third quatrain, the speaker again rebukes the young fellow for his selfish behavior for which the speaker is so often accusing him. The speaker uses his oft-repeated inquiry: how will you defend your behavior after you have squandered the precious time granted to you, if you do not take my sage advice and live up to your responsibilities?

The speaker is always attempting to persuade the young man that he has the best interests of the young fellow at heart as he continues his acts of persuasion. The speaker touts his befuddlement at just how the young man will be able to explain his selfish attitudes and behavior after the time has arrived for him leave this life.

If the young man leaves behind no comely heirs who can replace him and continue to present those pleasing qualities, the speaker feels that the young fellow will have no believable defense for his selfishness. The speaker often pretends to be confused or to lack understanding after he has charged the young fellow with of some odious quality such as officious vanity.

The Couplet: Sorrowful Final Years of Life

Thy unused beauty must be tombed with thee,

Which, used, lives th’ executor to be.

The speaker finally declaims that if the young man does not take a wife and spring off lovely children, the young fellow’s beauty can only die with him. The speaker has made it abundantly clear that such failure to act as the speaker wishes remains an example of sheer cruelty and failure to do his duty.

But if the young fellow would simply take the speaker’s guidance and employ his pleasing qualities appropriately, he will then be able to leave behind a living heir, who, after the death of the progenitor, will then be able to serve as the sire’s executor.

The speaker tries to urge the young man to follow his sage advice, by concocting a lonely scene of the young man after old age has crept upon him. The speaker continues creating scenarios that negatively portray the young man’s situation if the young fellow fails to follow the advice of the speaker. If the young man continues to remain unmarried and without offspring, the speaker predicts a sorrowful future for the young fellow.

The desire for pleasing, handsome children to replace the pleasing qualities of the young man after he has become too old to present those qualities continues to weigh on the speaker’s mind. Thus the speaker continues to employ his considerable talents in persuading and even enlightening the young man to follow his advice and do as the speaker wishes.

Shakespeare Sonnet 5 “Those hours, that with gentle work did frame”

The speaker in Shakespeare sonnet 5 “Those hours, that with gentle work did frame” continues fashioning his little dramas, attempting to persuade the young man to marry and procreate lovely offspring to preserve his youth and thus attain a certain degree of immortality.

Introduction with Text of Sonnet 5 “Those hours, that with gentle work did frame”

The speaker of sonnet 5 “Those hours, that with gentle work did frame” from the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence continues his dedication to creating his little dramas in order to convince the young man that he must marry and produce children to pass on his handsome features and and pleasing qualities.

This speaker is a crafty fellow, who now is setting forth a captivating comparison of the summer and winter seasons along with strategies to maintain pleasant physical features. In his persuasive discourse, the speaker attempts to appeal to the young man’s vanity, even as he attempts to encourage the young fellow’s sense of duty and responsibility.

Sonnet 5 “Those hours, that with gentle work did frame”

Those hours, that with gentle work did frame

The lovely gaze where every eye doth dwell,

Will play the tyrants to the very same

And that unfair which fairly doth excel;

For never-resting time leads summer on

To hideous winter, and confounds him there;

Sap check’d with frost, and lusty leaves quite gone,

Beauty o’ersnow’d and bareness every where:

Then, were not summer’s distillation left,

A liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass,

Beauty’s effect with beauty were bereft,

Nor it, nor no remembrance what it was:

But flowers distill’d, though they with winter meet,

Leese but their show; their substance still lives sweet.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 5 “Those hours, that with gentle work did frame”

This speaker continues to appeal to the young man’s vanity—one of his favorite strategies in his toolkit of persuasion. His goal remains ever the same, to convince the young man to marry and procreate lovely offspring.

First Quatrain: As the Passage of Time Continues to Ravage

Those hours, that with gentle work did frame

The lovely gaze where every eye doth dwell,

Will play the tyrants to the very same

And that unfair which fairly doth excel;

In the first quatrain of sonnet 5, the speaker reminds the young man that an unpleasant aspect of the passing of time is ever on his heals: on the one hand, it has worked well its magic in creating the young fellow to be a fine looking specimen.

But on the other hand, the passing of time will ultimately morph itself into a tyrant and transform all of his handsome, fine characteristics into the shriveled ugliness that comes with the ravages of old age. The young man, whose qualities remain presently quite attractive, causing “every eye [to] dwell” upon those pleasing features, therefore, is obligated to pass those qualities on to the next generation.

The speaker believes that time has crafted a marvelously, nearly perfect countenance for the young man; yet, time will also be unrelenting in changing those lovely youthful qualities into a pitiful, unflattering, old man.

The speaker is thus employing the images resulting from the damage wreaked by the passing of time to convince the young man that he should marry and spring off lovely children, who will be able to fill a new generation with the young man’s handsome features.

The speaker had earlier set forth the idea that a special kind of immorality could be attained simply through the process of procreation. He is basing his notion on the fact that progeny do often look like their parents. The sad fact also remains that sometimes children are not blessed with the same pleasing physical qualities enjoyed by the parent.

However, this speaker, who seems to be a betting man, is counting on the possibility that this young fellow’s offspring would be blessed with those same fine features, now enjoyed by the young man. The speaker never addresses the issue of true immortality, likely assuming that the young man is so vain that he would not notice such a fine distinction.

Second Quatrain: Dark vs Bright Seasons of Life

For never-resting time leads summer on

To hideous winter, and confounds him there;

Sap check’d with frost, and lusty leaves quite gone,

Beauty o’ersnow’d and bareness every where:

The speaker now asserts that time is “never-resting” as he then compares summer to winter. He describes winter as “hideous.” Naturally, the darkest, coldest season of the year could be thought of as “hideous” when the sap in the trees is no longer flowing smoothly because it is “check’d with frost.”

Metaphorically, the speaker then compares the sap in winter trees to human blood. The cold temperature keeps the sap from moving smoothly. Thus it will be similar to the young man’s blood after his physical encasement (body )has become ravaged by the frigidity of old age.

As the sap ceases flowing in the trees, the leaves fall from their branches, as hair falls from the heads of the aged, and the beauty of youth is obliterated by all sorts of physical infirmities.

Metaphorically, the “lusty leaves” compare to the physical attractiveness of the young man—those qualities that reflect the physical beauty to which other people have become attracted.

The young fellow should therefore take advantage of his “summer,” that is, his young adulthood, before “winter” or old age causes his blood to become lethargic, thus transforming his beautiful, youthful qualities, leaving them barren and unattractive.

The speaker has taken notice of the young man’s affection for his own physical characteristics. So the speaker knows he can appeal to the young fellow’s vanity. The speaker then dramatizes the physical facts of the aging process, rendering that process as stark as possible with his creative, fascinating metaphors.

This speaker seems to know that he can concoct an unlimited number of scenarios, in which to station the young man. He is also well aware of the many personality flaws suffered by the young man, and he can appeal to and exploit them for persuasion.

Third Quatrain: Metaphoric Summer and Winter

Then, were not summer’s distillation left,

A liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass,

Beauty’s effect with beauty were bereft,

Nor it, nor no remembrance what it was:

The speaker then dramatizes the summer’s essence as being preserved in the distillation process of flowers to make perfume. The speaker may also be referring to the process of distilling dandelion flowers into wine: “A liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass.” However, without the offspring of summer, the beauty that had existed would have disappeared, and no one would remember that summer had ever existed.

Again through metaphor, the speaker is comparing the result of summer to perfume or wine, trying to show the young man that re-creating his own likeness in lovely children would be a great gift to the world and also to himself. The speaker continues to enhance the positive qualities of the young man’s character even as he tempts him through his ignoble qualities including vanity and selfishness.

If the speaker can convince the young man to offer the gift of beautiful, pleasing children to the world, he can likely persuade him that his life will take on more importance than simply remaining a mere physical presence upon the earth for a brief period of time.

The Couplet: To Preserve Youth and Beauty

But flowers distill’d, though they with winter meet,

Leese but their show; their substance still lives sweet.

In the couplet, the speaker is again referring to the perfume/alcohol created during the summer season. The “flowers” were distilled to result in the “liquid prisoner.” The speaker reports that even though those flowers had to experience winter, they gave up only beauty to the eye of the beholder. Their “substance” or essence, however, became the liquid they yielded, and it “still lives sweet.”

The speaker continues to hope that his persuasion will convince the young man through his vanity and urge him to want to preserve his own youth, if only by proxy. But the speaker is simply asserting still another ploy to persuade the young man to marry and spring off pleasing children; thus the speaker is speaking to the young man’s vain quality as well as his sense of self.

Shakespeare Sonnet 6 “Then let not winter’s ragged hand deface”

Shakespeare sonnet 6 “Then let not winter’s ragged hand deface” may be considered as a companion piece to Shakespeare sonnet 5. The speaker opens by referring to the same metaphor he employed in the earlier sonnet, the distillation of flowers.

Introduction with Text of Sonnet 6 “Then let not winter’s ragged hand deface”

From the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence, sonnet 6 of “The Marriage Sonnets” continues the speaker’s attempts to persuade a young man to marry and produce beautiful offspring. As this sonnet sequence progresses, a number of fascinating metaphors and images emerge from the speaker’s literary tool kit.

The speaker’s passion becomes almost a frenzy as he begs, cajoles, threatens, and shames this young lad, trying to persuade the young fellow that he simply must marry and produce offspring that will perpetuate the lad’s fine qualities.

Sonnet 6 “Then let not winter’s ragged hand deface”

Then let not winter’s ragged hand deface

In thee thy summer, ere thou be distill’d:

Make sweet some vial; treasure thou some place

With beauty’s treasure, ere it be self-kill’d.

That use is not forbidden usury,

Which happies those that pay the willing loan;

That’s for thyself to breed another thee,

Or ten times happier, be it ten for one;

Ten times thyself were happier than thou art,

If ten of thine ten times refigur’d thee;

Then what could death do, if thou shouldst depart,

Leaving thee living in posterity?

Be not self-will’d, for thou art much too fair

To be death’s conquest and make worms thine heir.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 6 “Then let not winter’s ragged hand deface”

Sonnet 6 provides a companion piece to Shakespeare sonnet 5. Upon opening the sonnet, the speaker is referring to the same metaphor he employed in the earlier sonnet—the distillation of flowers.

First Quatrain: Creeping Old Age

Then let not winter’s ragged hand deface

In thee thy summer, ere thou be distill’d:

Make sweet some vial; treasure thou some place

With beauty’s treasure, ere it be self-kill’d.

The speaker begins by employing the adverbial conjunction “then” signaling that sonnet 6 is tied to sonnet 5. He admonishes the young man that the latter should not let creeping old age overtake his youth: the lad must produce an heir to stay that putrid stage of life.

Thus the speaker has the season of winter metaphorically functioning as old age and summer as youth, while the process of distillation metaphorically functions as the offspring. The speaker demands of the youth that he create “some vial” to contain the beauty that will be annihilated if the young fellow allows time to pass him by.

The speaker is admonishing the young man to “distill” his beauty by pouring that quality into a glass bottle, as a perfume or a liquor would be done. And again, the speaker emphasizes his signature note, “before it’s too late,” to nudge the young man in the direction toward which the speaker continues to point him—to marry and produce quality offspring.

Second Quatrain: A Money Metaphor

With beauty’s treasure, ere it be self-kill’d.

That use is not forbidden usury,

Which happies those that pay the willing loan;

That’s for thyself to breed another thee,

The speaker then switches to a money or finance metaphor. He asserts that by completing his assignment to procreate, the speaker will also be employing a proper station for this beauty.

By allowing his own lovely features to be inherited by his offspring, the young lad will enhance and brighten the entire universe. The young man is thus likened to those who repay debts after they have borrowed; after the loan is repaid, all parties are well pleased.

The speaker at the same time is implying that if the lad does not reproduce offspring to perpetuate his beauteous qualities, he will be like one who fails to satisfy his debt—a situation that will result in unhappiness and humiliation for all involved.

Then the speaker inserts a new notion that he has not heretofore offered; he now proposes the idea that if the young man sires ten offspring, then ten times the happiness will result. The speaker attempts to demonstrate the marvelous boon that ten heirs would be by numerically stating, “ten times happier, be it ten for one.”

Third Quatrain: Think Hard on Deathlessness

Or ten times happier, be it ten for one;

Ten times thyself were happier than thou art,

If ten of thine ten times refigur’d thee;

Then what could death do, if thou shouldst depart,

Leaving thee living in posterity?

The speaker admires his new solution so much that he repeats the number. He employs the entire force of his argument by asserting that ten offspring would offer ten times more happiness. The speaker then asks what misery could death cause as the happy father will be well ensconced in the lives of his progeny, thereby achieving a certain kind of immortality.

The speaker desires that the young man take it upon himself to think hard on his own desire for deathlessness and how that status would be accomplished by producing lovely offspring to carry on after the young fellow has left his body.

The speaker’s question remains rhetorical, as it implies that the lad could win the battle of death by leaving an heir, who would resemble the young man. Growing old, withering, and leaving this world would be outsmarted, if only the young fellow would marry and procreate, according to the speaker.

The Couplet: To Avoid Selfishness

Be not self-will’d, for thou art much too fair

To be death’s conquest and make worms thine heir.

Finally, the speaker demands that the young man not remain “self-will’d,” that is, thinking only of his own pleasure and enjoyment, wishing that the time period of the present could ever exist, and without sufficient cogitation on the future. The speaker desires to impart to the younger man the notion that the lad’s pleasing qualities are too valuable to permit “worms” to become “[his] heir.”

The speaker employs the unpleasantness of nature as well as nature’s loveliness and beauty—whichever seems to further his cause—in convincing the young lad that springing off heirs remains one of his most crucial duties in life. The speaker continues his efforts to persuade the young man to marry and procreate by portraying old age and death as utterly disagreeable.

And those qualities of old age and death are especially disagreeable wherein the aging one has not taken the necessary steps against self-destruction by marrying and procreating in order to continue the pleasing qualities of the father.

The speaker remains adamant in his demands. He varies his techniques, images, metaphors, and other elements of his little dramas, but he remains steadfast in his one goal, persuading the young man to marry and produce lovely children. At times, the speaker seems to be reading the young man’s mind in order to land on the particular set of images that he deems most workable in his attempts. to persuade.

Shakespeare Sonnet 7 “Lo! in the orient when the gracious light”

In Shakespeare sonnet 7 “Lo! in the orient when the gracious light,” the speaker, still trying to convince the young man that he should marry and procreate, is comparing metaphorically the young man’s aging process to the daily journey of sun traveling across the sky.

Introduction and Text of Sonnet 7 “Lo! in the orient when the gracious light”

The sun—that “hot glowing ball of hydrogen and helium – at the center of our solar system“— has always been a useful object for poets to employ metaphorically. And this talented poet makes use of it often and skillfully.

In sonnet 7, the speaker is comparing the age progression of the young lad to the sun’s diurnal journey across the sky. Earthlings adore the sun in the morning and at noon, but as it begins to set they divert their attention from that fantastic orb.

Playing on the vanity of the young man, the speaker urges the lad to take advantage of his time as an object of attention to attract a mate and produce offspring, for like the sun there will come a time when that attraction will fade as the star seems to do at sunset.

Sonnet 7 “Lo! in the orient when the gracious light”

Lo! in the orient when the gracious light

Lifts up his burning head, each under eye

Doth homage to his new-appearing sight,

Serving with looks his sacred majesty;

And having climb’d the steep-up heavenly hill,

Resembling strong youth in his middle age,

Yet mortal looks adore his beauty still,

Attending on his golden pilgrimage;

But when from highmost pitch, with weary car,

Like feeble age, he reeleth from the day,

The eyes, ’fore duteous, now converted are

From his low tract, and look another way:

So thou, thyself outgoing in thy noon,

Unlook’d on diest, unless thou get a son.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 7 “Lo! in the orient when the gracious light”

In sonnet 7, the speaker cleverly uses a pun, metaphorically comparing the young lad’s life trajectory to a diurnal journey of the sun across the sky.

First Quatrain: As the Sun Moves Through the Day

Lo! in the orient when the gracious light

Lifts up his burning head, each under eye

Doth homage to his new-appearing sight,

Serving with looks his sacred majesty;

The speaker in sonnet 7 commences his continuing appeal to the young man to sire a child by directing the young lad to muse on the movement of the sun through the day. After the sun appears in the morning as if waking up, people open their eyes in “homage to his new-appearing sight.” Earthlings are delighted with each new day’s dawning.

The appearance of the sun delights as it warms and brings all things into view, and earth folks seem to intuit that the sun possesses a “sacred majesty” when that bright org first appears in the sky each morning.

Second Quatrain: Admiration for Youth

And having climb’d the steep-up heavenly hill,

Resembling strong youth in his middle age,

Yet mortal looks adore his beauty still,

Attending on his golden pilgrimage;

After the sun rises and seems to stand overhead, earth folks go on admiring and adoring the bright star. And then the speaker makes it abundantly understandable that he is comparing through the device of metaphor the young lad’s youth to that of the daily sunrise and journey across the day.

The speaker announces, “Resembling strong youth in his middle age,” a period of time when folks will continue to admire both the sun’s and the young man’s beauty. And they will keep on treating him royally as he progresses through his “golden pilgrimage”—the sun’s literal golden daily trip across the sky and the young man’s most lustrous years from adulthood on into old age.

Third Quatrain: As Eyes Turn Away

But when from highmost pitch, with weary car,

Like feeble age, he reeleth from the day,

The eyes, ’fore duteous, now converted are

From his low tract, and look another way:

However, with the sun beyond the zenith and seemingly moving down in back of the earth again, folks no longer peer at the phenomenal beauty. And as the darkness of night veils the earth, they turn their eyes away and avert their attention from the once royal majesty that was the sun rising and the sun at midday.

After “feeble age” has caused the young lad to go wobbling like an old man, people will divert their attention from him as they do when the sun is going down. They will not continue to pay homage to that which is fleeing; they will then “look” the other way.

The Couplet: No One Will Be Looking

So thou, thyself outgoing in thy noon,

Unlook’d on diest, unless thou get a son.

Then the speaker in the couplet blatantly announces to the young man that if the latter permits his youthful beauty to grow dim as the sun grows dim in late evening, no one will be looking at the young fellow anymore, unless he sires an heir, more specifically a son.

Sonnet 7 relies on the compelling use of a pun, an entertaining poetic device, as well as the precise biological sex for his heir. The speaker thus far had not designated whether the offspring should be a daughter or a son that he so much yearns for the young man to father.

It has always been implied, however, that the child should be a male who can inherit both the father’s physical characteristics as well as his real property. In this sonnet, the speaker definitely specifies that the young lad will forsake his immortality “unless thou get a son.”

Metaphorically, the speaker is comparing the young man’s life journey to the sun’s daily journey across the sky; thus it is quite fitting that he would employ the term “son,” and the clever speaker undoubtedly held the notion that his pun was quite cute: sun and son. The prescient speaker is certain his readers will admire his skill in employing that literary device.

Shakespeare Sonnet 8 “Music to hear, why hear’st thou music sadly?”

In Shakespeare sonnet 8 “Music to hear, why hear’st thou music sadly?,” the speaker again uses his finest logic, attempting to convince the young man that the latter should wed and produce beautiful offspring.

Introduction with Text of Sonnet 8 “Music to hear, why hear’st thou music sadly?”

In sonnet 8 “Music to hear, why hear’st thou music sadly?” in “The Marriage Sonnets” from the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence, the speaker compares a happy marriage to musical harmony, hoping to evoke in the young lad the desire to attain that harmony in his life.

The speaker will be offering many different strategies for the same argument as to why the young man should hurry up and marry before old age sets in, destroying his youthful beauty.

And the speaker particularly encourages the young man to begat children as a way for his fine physical qualities to be passed on to the next generation. The clever speaker seems to revel in his own process of creating his little dramas.

Each sonnet becomes a showcase, a stage, and blank page upon which to create and perform his balancing act of producing interesting dramas as well as well-argued claims. This speaker has one goal in mind for his first 17 sonnets, and he clings to its mission with great gusto and zeal.

Sonnet 8 “Music to hear, why hear’st thou music sadly?”

Music to hear, why hear’st thou music sadly?

Sweets with sweets war not, joy delights in joy:

Why lov’st thou that which thou receiv’st not gladly,

Or else receiv’st with pleasure thine annoy?

If the true concord of well-tuned sounds,

By unions married, do offend thine ear,

They do but sweetly chide thee, who confounds

In singleness the parts that thou shouldst bear.

Mark how one string, sweet husband to another,

Strikes each in each by mutual ordering;

Resembling sire and child and happy mother,

Who, all in one, one pleasing note do sing:

Whose speechless song, being many, seeming one,

Sings this to thee: ‘Thou single wilt prove none.’

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 8 “Music to hear, why hear’st thou music sadly?”

The Shakespeare sonnet 8 finds the speaker employing a music metaphor along with his best logic and analyses to convince the young man that he should wed and produce pleasing offspring.

First Quatrain: The Metaphor of Music

Music to hear, why hear’st thou music sadly?

Sweets with sweets war not, joy delights in joy:

Why lov’st thou that which thou receiv’st not gladly,

Or else receiv’st with pleasure thine annoy?

The speaker employs a metaphor of music in attempting to persuade the young man to realize that both marriage as well a music produce a lovely harmony. The first quatrain finds the older speaker observing the young man’s glum response to some piece of music they have experienced.

The speaker asks the young man about this gloomy expression, stating, “Sweets with sweets war not, joy delights in joy.” According the speaker, the young man is a pleasingly handsome individual; therefore, he is a “sweet” man; thus, the speaker asserts that the young lad should discern the same qualities in the music that he himself possesses.

The speaker continues to query the young man about his response to the music by asking him if he would like to receive that which he was glad to have or if receiving what pleases him would disappoint him.

It sounds like a knotty question, but the speaker, as always, is attempting to influence the young man into believing that his status as a single, wifeless/childless man is a negative state of affairs.

The speaker’s verbal attempt remains colorful, employing sweetness, joy, and music as objects of pleasure, instilling in the young man the notion that the latter’s sweet qualities are too important not to be shared with the next generation.

Second Quatrain: Marriage as Pleasing as Musical Harmony

If the true concord of well-tuned sounds,

By unions married, do offend thine ear,

They do but sweetly chide thee, who confounds

In singleness the parts that thou shouldst bear.

The speaker wishes for the young man to comprehend that a harmonious life like musical melody is to be attained with a solid marriage. The metaphor of harmonious music seems to remain ineffectual because the young lad appears to have separated out individual parts of the music for pleasure instead hearing the sum of the harmonious parts.

And the speaker hopes to make the young man realize that a harmonious marriage which produces beautiful offspring is as pleasing to the world as a piece of beautiful music that has its various parts working together to produce the whole.

Third Quatrain: Strings That Play

Mark how one string, sweet husband to another,

Strikes each in each by mutual ordering;

Resembling sire and child and happy mother,

Who, all in one, one pleasing note do sing:

The speaker then compares the family of father, mother, and child to the strings that when played in the proper sequence result in the lovely song: “one pleasing note do sing.”

The speaker hopes that the young man will accept his fervent urgings to marry and take on a family, instead of allowing his good qualities to waste away in the frivolity of bachelorhood.

The speaker is convinced that if the young man fails to pass on his pleasing features, he will have wasted his life. The speaker’s use of the musical metaphor shows the speaker’s emphasis on physical beauty. He also refers to the mother of those beautiful offspring.

If the young man marries and produces those lovely heirs, the union will also be adding to the world a “happy mother.” The pleasing family filled with grace and beauty will enhance the world as beautiful music from a symphony does.

The Couplet: No Family, No Music

Whose speechless song, being many, seeming one,

Sings this to thee: ‘Thou single wilt prove none.’

The couplet finds the speaker, as usual, nearly begging the young man to understand that if he remains a bachelor, thus producing no family, no offspring, his life will have no music.

And the young fellow will continue to remain without the wonderful qualities of harmony and beauty. The music metaphor, thus, has offered beauty as a goal as well as the peace and harmony that the speaker desires for the young man.

Shakespeare Sonnet 9 “Is it for fear to wet a widow’s eye”

In sonnet 9“Is it for fear to wet a widow’s eye,” the speaker queries the young man about another possible reason for his remaining single: does he fear leaving some poor woman a widow?

Introduction with Text of Sonnet 9 “Is it for fear to wet a widow’s eye”

In Shakespeare sonnet 9 from the thematic group “The Marriage Sonnets” from the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence, the older and supposedly wiser speaker is now querying the lad about another likely reason for the young man’s remaining single: does he perhaps fear causing some poor woman to become a member in that sorrowful lot called widowhood?

The speaker knows this supposition is without merit. He is merely conjuring up every accusation that he can hurl at the young fellow as he tries to influence the young man’s behavior. The speaker’s dramas keep getting more and more stark as he seems to grow more and more desperate to have the young man marry and produce beautiful offspring.

It seems that no accusation is too severe. Appealing to the young man’s vanity seems to get him nowhere, so he has decided to appeal to the lad’s sense of shame. No young man would want to be accused of committing murder like a common misanthrope.

Sonnet 9 “Is it for fear to wet a widow’s eye”

Is it for fear to wet a widow’s eye,

That thou consum’st thy self in single life?

Ah! if thou issueless shalt hap to die,

The world will wail thee like a makeless wife;

The world will be thy widow and still weep

That thou no form of thee hast left behind,

When every private widow well may keep

By children’s eyes, her husband’s shape in mind:

Look! what an unthrift in the world doth spend

Shifts but his place, for still the world enjoys it;

But beauty’s waste hath in the world an end,

And kept unused the user so destroys it

No love toward others in that bosom sits

That on himself such murd’rous shame commits.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 9 “Is it for fear to wet a widow’s eye”

Sonnet 9 finds the speaker querying the young man about yet an additional possible, though rather absurd, reason for his failure to marry: does the young man fear leaving some poor woman a widow?

First Quatrain: A Blunt Question

Is it for fear to wet a widow’s eye,

That thou consum’st thy self in single life?

Ah! if thou issueless shalt hap to die,

The world will wail thee like a makeless wife;

In the first quatrain, the speaker bluntly puts the question to the young man: do you linger in bachelorhood because you are afraid of causing some young woman to suffer widowhood if you should die?

The speaker goes on approaching the subject from every angle, as he chides the young lad for not taking a wife. The notion now is crossing the speaker’s mind that the young man may not want to take the chance of leaving behind a crying widow.

The speaker as usual is creating what he seems to deem a solid suggestion; yet, it remains a rather flimsy, straw man which he will now have to allow the young man to watch him burn down.

But the speaker’s spin on such a fear is that if the young man dies “issueless,” that is, without offspring, he will make the whole world sad, crying for him, not just a poor woman who would then be without a mate upon his death. Thus the speaker wants the young man to think in broader terms than just one family.

Second Quatrain: Mourning the Loss of a Generation

The world will be thy widow and still weep

That thou no form of thee hast left behind,

When every private widow well may keep

By children’s eyes, her husband’s shape in mind:

The speaker frames his claim quite clearly as he repeats: not only one woman would weep if you shuffle off, but the whole world with weep and suffer if you fail to leave without issuing forth some lovely offspring to populate the next generation.

If the young man died, the world would not only mourn his loss, but it would also mourn the fact that such a fine, human specimen left behind no beautiful children to take his place.

If, however, the young man takes the advice of his elder, upon his possible demise, his widow would have their beautiful children who allow her to remember and thereby enjoy the pleasing appearance of her spouse.

The speaker hopes again to play upon the sympathy of the young man, while offering him logical possibilities to consider. The young man’s single life is found wanting in every way in the eyes of this speaker, who might be considered meddling in affairs which are none of his business.

Third Quatrain: Urging with Logic

Look! what an unthrift in the world doth spend

Shifts but his place, for still the world enjoys it;

But beauty’s waste hath in the world an end,

And kept unused the user so destroys it.

In the third quatrain, the speaker offers another supposedly logical argument to support his urging the young man to marry and produce offspring. When a spendthrift extravagantly squanders his money on things he does not need, he does not really do any damage in the world; he merely moves things around a bit.

The money and the material things still belong to the world. But when one wastes one’s beauty, one wastes something of value, and its value is precious because it will end. If one does not pass on one’s beauty and pleasing qualities by siring pleasing offspring, he simply destroys that beauty. The speaker is playing on the vanity as well as the sympathy of the young man, as he employs his powers of persuasion.

The Couplet: Misanthropic Selfishness

No love toward others in that bosom sits

That on himself such murd’rous shame commits.

In the couplet, the speaker hurls a stark but exaggerated notion: that the young man’s behavior is bordering on misanthropy, as he employs the “either/or” fallacy, implying that if the young man does not love others, he surely must hate them to the point of murder.

The speaker opines that the young man could not possess a loving heart and affection toward his fellow humans, if he is so selfish as to waste his beauty and pleasing qualities on himself, while failing to father the next generation of beauty and pleasing qualities. The speaker accuses the young man of committing a “murderous shame”—an exaggeration aimed at stirring the young fellow to action.

Shakespeare Sonnet 10 “For shame! deny that thou bear’st love to any”

In sonnet 10 “For shame! deny that thou bear’st love to any,” the speaker challenges the young man’s sense of self, regarding his love and affection for others. The speaker exaggerates the lack as “murderous hate.”

Introduction and Text of Sonnet 10 “For shame! deny that thou bear’st love to any”

In sonnet 10 from the thematic group “The Marriage Sonnets” in the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence, the speaker so desperately desires the young man to marry and produce beautiful offspring that he resorts to exaggerating the young man’s likely egotism.

This sonnet sequence demonstrates the creative power and talent of the speaker’s ability to dramatize his continuing and deepening wish that the young man heed his advice. The insistent speaker ultimately begs the lad to do it for the speaker even if he will not do it for himself.

Sonnet 10 “For shame! deny that thou bear’st love to any”

For shame! deny that thou bear’st love to any

Who for thyself art so unprovident.

Grant, if thou wilt, thou art belov’d of many,

But that thou none lov’st is most evident;

For thou art so possess’d with murderous hate

That ’gainst thyself thou stick’st not to conspire,

Seeking that beauteous roof to ruinate

Which to repair should be thy chief desire.

O! change thy thought, that I may change my mind:

Shall hate be fairer lodg’d than gentle love?

Be, as thy presence is, gracious and kind,

Or to thyself at least kind-hearted prove:

Make thee another self, for love of me,

That beauty still may live in thine or thee.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 10 “For shame! deny that thou bear’st love to any”

The speaker is now challenging the young man’s sense of self, vis-à-vis his love and affection for others. The speaker then exaggerates his possible lack as being “murderous hate.” The speaker’s employment of exaggeration often adds to the drama of his pleadings.

First Quatrain: Accusations of Selfishness

For shame! deny that thou bear’st love to any

Who for thyself art so unprovident.

Grant, if thou wilt, thou art belov’d of many,

But that thou none lov’st is most evident;

The speaker in the couplet of sonnet 9 “Is it for fear to wet a widow’s eye” had accused the young man: you must hold a deadly contempt for your fellow man to remain so utterly selfish.

In this sonnet 10 “For shame! deny that thou bear’st love to any,” the speaker carries on with this theme of accusation against the young man for loving no one but himself. The speaker has often teased and rebuked the young man for his selfishness; thus now the speaker is labeling such selfishness a murderous crime. An exaggeration, for sure!

The speaker yells accusingly,”For shame!” And then the older man provokes the young man to repudiate the fact that he is negligent of others, that the latter is, in fact, a charitable individual to others, at least as much so as they are to him.

The speaker refreshes the young lad’s memory that the latter certainly is cognizant that many other people feel love and affection for the young lad, but that the young man does not reciprocate that affection remains obvious—”is most evident.”

Second Quatrain: Exaggeration, Reprimands, Deadly Hatred

For thou art so possess’d with murderous hate

That ’gainst thyself thou stick’st not to conspire,

Seeking that beauteous roof to ruinate

Which to repair should be thy chief desire.

The speaker continues to exaggerate his claims in the second quatrain as he upbraids the young lad for holding deadly hatred in his heart. This speaker wants to impress the young man with the notion that such disaffection negatively impacts the interests of the latter. If the young man were to allow destruction of his own home and did nothing to stop it, he would be very foolish.

The speaker pours shame on such an attitude, asserting that the younger man should seek to rebuild his home from any damage. His “chief desire” should be the reconstruction of house or heart.

Of course, the speaker is repeating the employment of his metaphor as he nudges the young man to guard himself from the ruination of leaving this life while leaving behind no sons and daughters.

Third Quatrain: Begins Begging

O! change thy thought, that I may change my mind:

Shall hate be fairer lodg’d than gentle love?

Be, as thy presence is, gracious and kind,

Or to thyself at least kind-hearted prove:

In the third quatrain, the speaker has continued his begging of the young man to change his thinking so the speaker can also change his own notions. The speaker does not wish to continue to believe that such heinous crimes of hate are actually nursed and nurtured in the heart of this beautiful, pleasant young individual.

Fashioned as a rhetorical question, the speaker queries the lad whether it is easier to hate or easier to love. Again, the speaker is trying to convince the young man that the former’s argument can be well supported. The speaker then gives the lad a command, telling him to use kindness and grace because such qualities constitute the lad’s appearance.

By showing his love and affection for a woman and producing an heir, the young man will be showing that he can take care of himself. The speaker has already demonstrated the bitter coldness, loneliness, and isolation of dying without leaving an heir. Now, he wants the lad to, at least, be kind to himself.

The Couplet: Do It for Me!

Make thee another self, for love of me,

That beauty still may live in thine or thee.

In the couplet, the speaker invokes his own position in the young man’s heart as he commands the lad to produce offspring, even for the speaker’s sake as well as his own. If the young will not produce the offspring solely for himself, then the speaker asks him to do so for the speaker. And then the speaker returns to the perpetuation of beauty theme.

Although there are many reasons for procreating offspring, the passing on of beauty is one of the most important for a vain young man. At least, the speaker is counting on that vanity being a significant part of the equation.

Shakespeare Sonnet 11 “As fast as thou shalt wane, so fast thou grow’st”

In sonnet 11 “As fast as thou shalt wane, so fast thou grow’st,” the older, persuasive speaker continues to urge the young man to marry and produce pleasing offspring. The clever speaker seems to strongly desire a son-in-law who will bestow a pleasing grandchild upon him.

Introduction and Text of Sonnet 11 “As fast as thou shalt wane, so fast thou grow’st”

In “Marriage Sonnet” 11 from the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence, the speaker continues to evoke the young man’s pleasing qualities, claiming that the young fellow has an obligation to marry and pass them on to offspring.

The older man seems to believe strongly that the older generation lives through the younger one, or so he would have the young man believe, as long as that notion props up the speaker’s argument.

The speaker, with each new drama, demonstrates his creative ability to invent arguments and present them in new and entertaining ways. As he grows more desperate that the young man produce offspring, the speaker grows more inventive, employing colorful and varied metaphors and exciting, bracing images.

Sonnet 11 “As fast as thou shalt wane, so fast thou grow’st”

As fast as thou shalt wane, so fast thou grow’st,

In one of thine, from that which thou departest;

And that fresh blood which youngly thou bestow’st,

Thou mayst call thine when thou from youth convertest,

Herein lives wisdom, beauty, and increase;

Without this folly, age, and cold decay:

If all were minded so, the times should cease

And threescore year would make the world away.

Let those whom nature hath not made for store,

Harsh, featureless, and rude, barrenly perish:

Look, whom she best endow’d, she gave thee more;

Which bounteous gift thou shouldst in bounty cherish:

She carv’d thee for her seal, and meant thereby,

Thou shouldst print more, not let that copy die.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 11 “As fast as thou shalt wane, so fast thou grow’st”

It is likely that the young man in “The Marriage Sonnets” is Henry Wriothesley, the third earl of Southampton, who is being urged to marry Elizabeth de Vere, the oldest daughter of the writer of the Shakespeare sonnets, Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford.

The older, persuasive speaker continues to urge the young man to marry and produce pleasing offspring. The clever speaker seems to strongly desire a son-in-law who will bestow pleasing grandchildren upon him.

First Quatrain: The Imploring Continues

As fast as thou shalt wane, so fast thou grow’st,

In one of thine, from that which thou departest;

And that fresh blood which youngly thou bestow’st,

Thou mayst call thine when thou from youth convertest,

The speaker in this sonnet continues to implore the young man to marry and produce offspring. This time he is chiding the young fellow, reminding him that he will grow old and wither.

But if the younger man will just listen to the older, mature fellow, he can mitigate the difficulty: his good looks and amiable personality will live on in his heir, or so the speaker appears to believe. The speaker has, at least, convinced himself that people continue living in their offspring.

The speaker likely only marginally believes such tripe and still has no compunction against using the notion to persuade the young man to marry his daughter. The speaker tries to persuade the young man to believe that his own blood will then be freshened in his offspring, even as the blood in his body becomes broken and stale.

Second Quatrain: To Achieve Wisdom

Herein lives wisdom, beauty, and increase;

Without this folly, age, and cold decay:

If all were minded so, the times should cease

And threescore year would make the world away.

The speaker urges the young man to believe that the latter will be wise in his behavior only if he marries and has children. Only by reproducing will he offer beautiful, wonderful acts to the world.

He will be productive instead of destructive, giving to the world, instead of merely taking from it. The speaker fears that by aging without reproducing, the young man will eventually have to give in to “cold decay.” But if the young fellow has produced offspring, he will avoid the pain folly of growing old alone and failing the world by leaving it without his progeny.

The speaker then pours out the old chestnut that goes, what if everyone behaved as callously as you, not marrying and reproducing? Well, according to the speaker, the world would come to an end in only two or three generations. A dour thought for sure, something for the young to cogitate upon.

Third Quatrain: Brutish Prigs and Their Ilk

Let those whom nature hath not made for store,

Harsh, featureless, and rude, barrenly perish:

Look, whom she best endow’d, she gave thee more;

Which bounteous gift thou shouldst in bounty cherish: