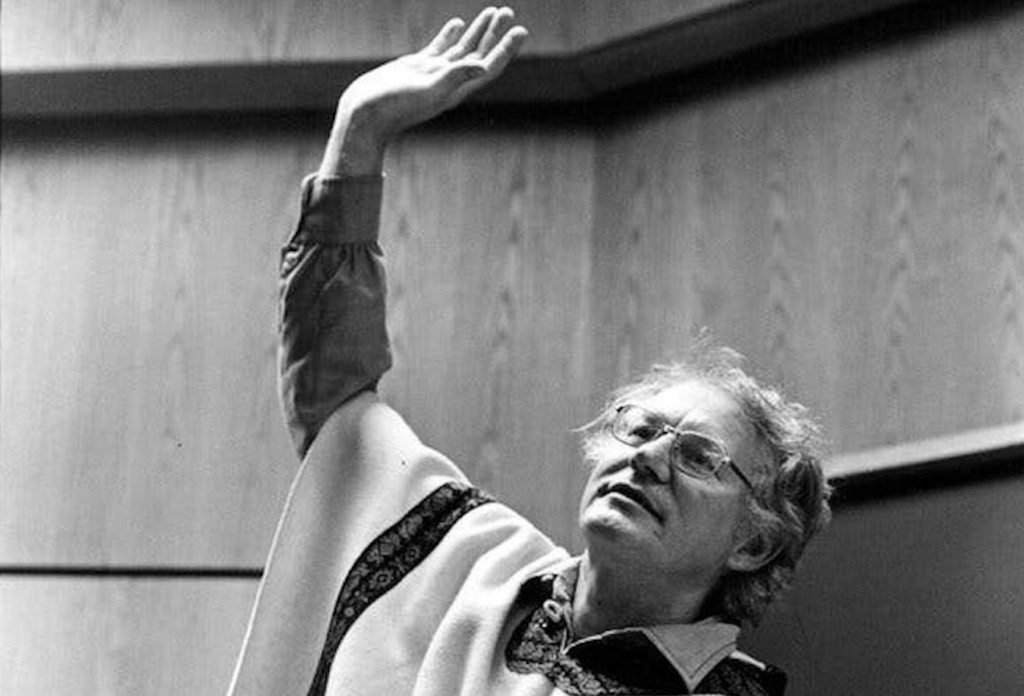

Image: Robert Bly – NYT– Robert Bly striking one of his melodramatic poses

Robert Bly’s “The Cat in the Kitchen” and “Driving to Town Late to Mail a Letter”

The following sample pieces of doggerel “The Cat in the Kitchen” and “Driving to Town Late to Mail a Letter” by Robert Bly exemplify the style of the poetaster and the types of subjects he addresses.

Introduction with Text of “The Cat in the Kitchen”

Two versions of this piece of Robert Bly doggerel are extant; one is titled “The Cat in the Kitchen,” and at the other one is titled “The Old Woman Frying Perch.” They both suffer from the same nonsense: the speaker seems to be spouting whatever enters his head without bothering to communicate a cogent thought.

Bly’s 5-line piece “Driving to Town Late to Mail a Letter” consists of a fascinating conglomeration of images that results in a facile display of redundancy and an unfortunate missed opportunity.

Robert Bly’s penchant for nonsense knows no bounds. Most of his pieces of doggerel suffer from what seems to be an attempt to engage in stream-of-consciousness but without any actual consciousness. The following summary/paraphrase of Bly’s “The Cat in the Kitchen” demonstrates the poverty of thought from which this poetaster suffers as he churns out his doggerel:

A man falling into a pond is like the night wind which is like an old woman in the kitchen cooking for her cat.

About American readers, Bly once quipped that they “can’t tell when a man is counterfeiting and when he isn’t.” What might such an evaluation of one’s audience say about the performer? Is this a confession? Bly’s many pieces of doggerel and his penchant for melodrama as he presents his works suggest that the man was a fake and he knew it.

The Cat in the Kitchen

Have you heard about the boy who walked by

The black water? I won’t say much more.

Let’s wait a few years. It wanted to be entered.

Sometimes a man walks by a pond, and a hand

Reaches out and pulls him in.

There was no

Intention, exactly. The pond was lonely, or needed

Calcium, bones would do. What happened then?

It was a little like the night wind, which is soft,

And moves slowly, sighing like an old woman

In her kitchen late at night, moving pans

About, lighting a fire, making some food for the cat.

Commentary on “Cat in the Kitchen”

The two versions of this piece that are extant both suffer from the same nonsense: the speaker seems to be spouting whatever enters his head without bothering to connect a cogent thought to his images. Unfortunately, that description seems to be the modus operandi of poetaster Bly.

The version titled “The Cat in the Kitchen” has three versagraphs, while the one titled “The Old Woman Frying Perch” boasts only two, as it sheds one line by combining lines six and seven from the Cat/Kitchen version.

First Versagraph: A Silly Question

Have you heard about the boy who walked by

The black water? I won’t say much more.

Let’s wait a few years. It wanted to be entered.

Sometimes a man walks by a pond, and a hand

Reaches out and pulls him in.

In Robert Bly’s “The Cat in the Kitchen,” the first versagraph begins with a question, asking the audience if they had heard about a boy walking by black water. Then the speaker says he will not “say much more” when, in fact, he has only asked a question. If he is not going to say much more, he has ten more lines in which not to say it. However, he then makes the odd demand of the audience that they wait a few years.

The speaker’s command implies that readers should stop reading the piece in the middle of the third line and begin waiting”a few years.” Why do they have to wait? How many years? By the middle of the third line, this piece has taken its readers down several blind alleys. So next, the speaker, possibly after waiting a few years, begins to dramatize his thoughts: “It wanted to be entered.” It surely refers to the black water which is surely the pond in the fourth line.

The time frame may, in fact, be years later because now the speaker offers the wobbly suggestion that there are times during which a man can get pulled into a pond by a hand as he walks by the body of water. The reader cannot determine that the man is the boy from the first line; possibly, there have been any number of unidentified men whom the hand habitually stretches forth to grab.

Second Versagraph: Lonely Lake Needing Calcium

There was no

Intention, exactly. The pond was lonely, or needed

Calcium, bones would do. What happened then?

The second verse paragraph offers the reasoning behind a pond reaching out its hand and grabbing some man who is walking by. The pond didn’t exactly intend to grab the man, but because it was “lonely” or “needed / Calcium,” it figured it would ingest the bones from the man.

Then the speaker poses a second question: “What happened then?” This question seems nonsensical because it is the speaker who is telling this tale. But the reader might take this question as a rhetorical device that merely signals the speaker’s intention to answer the question that he anticipates has popped into the mind of his reader.

Third Versagraph: It Was Like What?

It was a little like the night wind, which is soft,

And moves slowly, sighing like an old woman

In her kitchen late at night, moving pans

About, lighting a fire, making some food for the cat.

Now the speaker tells the reader what it was like. There is a lack of clarity as to what the pronoun “it” refers. But readers have no choice but take “it” to mean the phenomenon of the pond reaching out its hand, grabbing a man who was walking by, and pulling him into the water because it was “lonely, or needed / Calcium.”

Thus this situation resembles what? It resembles soft, night wind which resembles and old lady in her kitchen whipping up food for her cat. Now you know what would cause a lonely, calcium-deficient pond to reach out and grab a man, pull him into its reaches, and consequently devour the man to get at his bones.

Alternate Version: “The Old Woman Frying Perch”

In a slightly different version of this work called “Old Woman Frying Perch,” Bly used the word “malice” instead of “intention.” And in the last line, instead of the rather flabby “making some food for the cat,” the old woman is “frying some perch for the cat.”

The Old Woman Frying Perch

Have you heard about the boy who walked by

The black water? I won’t say much more.

Let’s wait a few years. It wanted to be entered.

Sometimes a man walks by a pond, and a hand

Reaches out and pulls him in. There was no

Malice, exactly. The pond was lonely, or needed

Calcium. Bones would do. What happened then?

It was a little like the night wind, which is soft,

And moves slowly, sighing like an old woman

In her kitchen late at night, moving pans

About, lighting a fire, frying some perch for the cat.

For Donald Hall

While the main problem of absurdity remains, this piece is superior to “The Cat in the Kitchen” because of two changes: “malice” is more specific than “intention,” and “frying perch” is more specific than “making food.”

However, the change in title alters the potential focus of each piece without any actual change of focus. The tin ear of this poetaster has resulted in two pieces of doggerel, one just a pathetic as the other. Robert Bly dedicates this piece to former poet laureate, Donald Hall—a private joke, possibly?

Introduction with Text of “Driving to Town Late to Mail a Letter”

Technically, this aggregate of lines that constitute Robert Bly’s “Driving to Town to Mail a Letter” could be considered a versanelle. The style of poem known as a versanelle is a short narration that comments on human nature or behavior and may employ any of the usual poetic devices. I coined this term and several others to assist in my poem commentaries.

Robert Bly’s “Driving to Town to Mail a Letter” does make a critical comment on human nature although quite by accident and likely not at all what the poet attempted to accomplish. Human beings do love to waste time although they seldom like to brag about it or lie about it, as seems to be case with the speaker in this piece.

Driving to Town Late to Mail a Letter

It is a cold and snowy night. The main street is deserted.

The only things moving are swirls of snow.

As I lift the mailbox door, I feel its cold iron.

There is a privacy I love in this snowy night.

Driving around, I will waste more time.

Commentary on “Driving to Town Late to Mail a Letter”

This 5-line piece by doggerelist Robert Bly simply stacks untreated image upon image, resulting in a stagnant bureaucracy of redundant blather. The poet missed a real opportunity to make this piece meaningful as well as beautiful.

First Line: Deserted Streets on a Cold and Snowy Night

It is a cold and snowy night. The main street is deserted.

The first line consists of two sentences; the first sentence asserts, “It is a cold and snowy

night.” That sentence echoes the line, “It was a dark and stormy night, by Edward George Bulwer-Lytton, whose name became synonymous with atrocious writing for that line alone.

There is a contest named for him, “The Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest,” with the subtitle where WWW means “Wretched Writers Welcome.” The second sentence proclaims the emptiness of main street. The title of the poem has already alerted the reader that the speaker is out late at night, and this line supports that claim that he is out and about so late that he is virtually the only one out.

This assertion also tells that reader that the town must be a very small town because large towns will almost always have some activity, no matter how late, no matter how cold.

Second Line: Only the Swirling Snow

The only things moving are swirls of snow.

The second line reiterates the deserted image of the first line’s second sentence, claiming that the only movement about his was the swirling snow. Of course, if the street were deserted, there would be no activity, or virtually no activity, so the speaker’s redundancy is rather flagrant.

The reader already knows there is snow from the first image of a cold and snowy night; therefore, the second line is a throwaway line. The speaker is giving himself only five lines to convey his message, and he blows one on a line that merely repeats what he has already conveyed, instead of offering some fresh insight into his little jaunt into town.

Third Line: Cold Mailbox Door

As I lift the mailbox door, I feel its cold iron

The third line is incredible in it facileness: the speaker imparts the information that he can feel the cold iron of the mailbox door as he lift it before depositing his letter. Such a line might be expected in a beginning poet’s workshop efforts.

The speaker had to have a line that shows he is mailing a letter, and he, no doubt, thinks this does it while adding the drama of “lift[ing] the mailbox door” and adding that he feels the coldness in the letter-box’s iron.

It’s a lame drama at best; from the information offered already both the cold iron and lifting the mailbox lid are already anticipated by the reader, meaning this line adds nothing to the scene.

Fourth Line: “There is a privacy I love in this snowy night”

There is a privacy I love in this snowy night

This line offers the real kernel of poetry for this conglomeration of lines. If the speaker had begun with this line, perhaps revising it to “I love the privacy of a snowy night,” and let the reader go with him to mail his letter, the experience could have been an inspiring one.

The images of the cold, snowy night of privacy, the deserted main street, the swirls of snow, the mailbox door could all have been employed to highlight a meaningful experience. Instead, the poetaster has missed his opportunity by employing insipid redundancy resulting in the flat, meaningless verse.

Fifth Line: Wasting Time Driving Around

Driving around, I will waste more time

The final line gives the flavor of James Wright’s “I have wasted my life” in his excellent poetic performance, “Lying In A Hammock At William Duffy’s Farm In Pine Island, Minnesota.”

There is a major difference between Wright’s poem and Bly’s doggerel: Wright’s speaker is believable, genuine, authentic. Bly’s empty verse is quite the opposite in every aspect, especially as Bly’s speaker proclaims he will ride around “wasting more time.” That claim is non-sense. Does he actually believe that mailing a letter is a waste of time? If he does, he has not made it clear why he would think that. It just seems that he has forgotten what the poem is supposed to be about.

Image: Robert Bly painting by Mark Horst

On My Meeting with This Sacred Cow of Po-Biz

In Memoriam: Robert Bly

December 23, 1926 – November 21, 2021

Requiescat in Pace.

Poetaster Robert Bly, one of the greatest flim-flam artists that po-biz has ever foisted upon the literary world, has passed on to his reward. Still, Bly remains one of the sacred cows of the contemporary literary world—so often praised that most critics, scholars, and commentarians shy away from pointing out the failings of this celebrated poetaster.

Ironically, among his hagiographies will remain criticism like the one by Suzanne Gordon, “‘Positive Patriarchy’ Is Still Domination: ‘Iron John’: Robert Bly’s devoted followers seem not to grasp what his message really means to women.”

While his recycled mythos, Iron John, surely earned him more financial rewards and much more recognition that his doggerel ever had, that twisted tome will also remain as testimony to the man’s warped thinking. Ironic indeed that the man who thought of himself as a feminist turned out not to have had a feminist bone in his body.

I met Robert Bly at Ball State University during a poetry workshop in the summer 1977. He held private sessions to offer us budding poets criticism of our poetic efforts. As I approached him, he planted a big kiss upon my lips before beginning the critique. Shocked at the impertinence, nevertheless, I just figured that was his way and then flung the incident down the memory hole.

The advice he offered regarding my poem was less than worthless. For example, I had a line, “slow as sorghum on the lip of a jar.” He called that vague and suggested that I somehow work my grandmother into the line, something like “my grandmother’s jar had a rim of sorghum.” (I was 31 years old at the time, but no doubt looked little more than 12).

That idiotic suggestion has colored my view of the man’s poetry, even more than his deceitful claims of “translations.” At the same workshop, he had taught a group of us how to “translate” poems, which was little more than reworking other people’s actual translations.

Anyway, may he rest in peace. He was persistent in his folly, and although William Blake infamously opined, “If a fool persists in his folly, he becomes wise,” it remains doubtful that claim actually applies, especially in Bly’s case.

🕉

You are welcome to join me on the following social media:

TruthSocial, Locals, Gettr, X, Bluesky, Facebook, Pinterest

🕉

Share