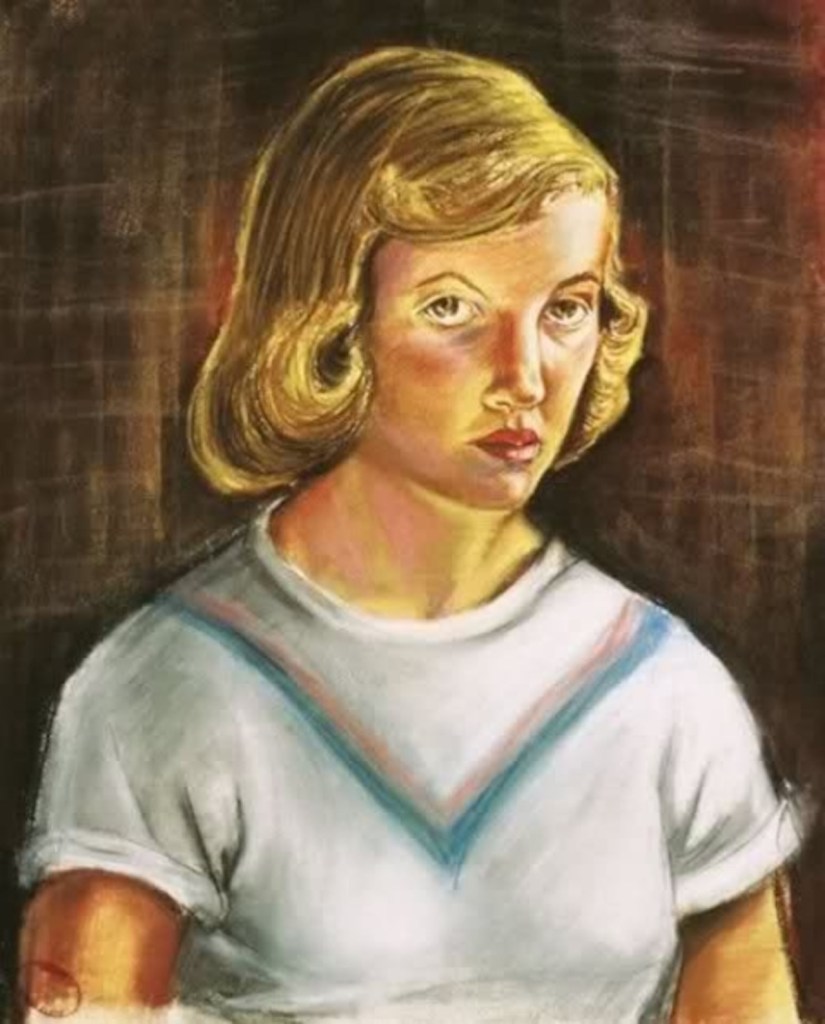

Image: Sylvia Plath

Sylvia Plath’s “Mirror”

The speaker in Sylvia Plath’s masterpiece “Mirror” employs a double metaphor of personifying a mirror and then a lake to report the experience of observing a woman obsessed with the disfiguring of her aging face.

Introduction with Text of “Mirror”

One of the best American poems of the 20th century, Sylvia Plath’s “Mirror” plays out in only two unrimed, nine-line verse paragraphs (veragraphs). The theme of the poem focuses on the reality of the aging process. The personified mirror dramatizes its amazing skill in reflecting whatever is placed before it exactly as the object is.

A lake serving as a mirror performs the same function of truth-telling. It is the mirror as lake, however, who is assigned the privilege of reporting the flailing agitation and tears of the woman who watches and senses that her aging face resembles “a terrible fish” that is rising toward her.

The death of Sylvia Plath at the tender age of thirty renders unto this awesome poem an uncanny quality. Because Plath left this earth at such an early age, the poet put an end to the actuality that she could have undergone the aging process as the woman in the poem is doing.

Plath is grouped with the 20th century “Confessional Poets,” but she often wrote poems that cannot be labeled confessional in that they do not reflect her life experience. Rather than confessing in “Mirror,” the young poet is merely speculating through a speaker, as most poets of any stripe usually do.

Mirror

I am silver and exact. I have no preconceptions.

Whatever I see I swallow immediately

Just as it is, unmisted by love or dislike.

I am not cruel, only truthful‚

The eye of a little god, four-cornered.

Most of the time I meditate on the opposite wall.

It is pink, with speckles. I have looked at it so long

I think it is part of my heart. But it flickers.

Faces and darkness separate us over and over.

Now I am a lake. A woman bends over me,

Searching my reaches for what she really is.

Then she turns to those liars, the candles or the moon.

I see her back, and reflect it faithfully.

She rewards me with tears and an agitation of hands.

I am important to her. She comes and goes.

Each morning it is her face that replaces the darkness.

In me she has drowned a young girl, and in me an old woman

Rises toward her day after day, like a terrible fish.

Reading of “Mirror”

Commentary on “Mirror”

The poem “Mirror” is arguably Sylvia Plath’s best poetic effort, and it is arguably also one of the best poems in American poetry.

First Versagraph: The Mirror Speaks

I am silver and exact. I have no preconceptions.

Whatever I see I swallow immediately

Just as it is, unmisted by love or dislike.

I am not cruel, only truthful ‚

The eye of a little god, four-cornered.

Most of the time I meditate on the opposite wall.

It is pink, with speckles. I have looked at it so long

I think it is part of my heart. But it flickers.

Faces and darkness separate us over and over.

The personified mirror opens the poem with a clear and accurate boast that he holds no prior prejudice against or for whatever appears before him. The mirror continues to proclaim his uncanny truthful ability for over half the versagraph. He reports that he takes in whatever is placed before him with no compunction to change the subject in any way.

The mirror cannot be moved by emotion as human beings are so motivated. The mirror simply reflects back the cold hard facts, unfazed by human desires and whims. The mirror does, however, seem almost to possess the human quality of pride in its ability to remain objective.

As the mirror continues his objective reporting, he claims that he is “not cruel, only truthful.” Again, he is making his case for complete objectivity, making sure his listeners understand that he always portrays each object before him as the object actually is.

However, again he might go a little too far, perhaps spilling his pride of objectivity into the human arena, real as he proclaims himself to be as the eye of “a little god, four-cornered.” By overstating his qualities, and by taking himself so seriously as to deify himself, he begins to lose his credibility.

Bu then as the listener/reader may be starting to waver from too much truth telling, the mirror jolts the narrative to what he actually does: he habitually renders the color of the opposite wall that has speckles on it. And he avers that he has concentrated so long on that wall that he feels that the wall might be part of his own heart.

The listener/reader can then understand that a mirror with a heart might actually tend to exaggerate and even take on some tinge of human emotion, even though it is likely that a mirror’s heart would toil quite differently from the heart of a human being.

The mirror confesses that as the objects confront him, as these “faces” and “darkness” come and go, they effect a flicker that would no doubt agitate the mirror’s sensibilities, regardless of how objective and truthful the mirror remains in human terms.

Second Versagraph: The Lake Metaphor

Now I am a lake. A woman bends over me,

Searching my reaches for what she really is.

Then she turns to those liars, the candles or the moon.

I see her back, and reflect it faithfully.

She rewards me with tears and an agitation of hands.

I am important to her. She comes and goes.

Each morning it is her face that replaces the darkness.

In me she has drowned a young girl, and in me an old woman

Rises toward her day after day, like a terrible fish.

Reading a poem can deliver the reader into a state of “narrosis”—a state once rendered by Samuel Taylor Coleridge as a “willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith.” A reader must allow him/herself to believe, if only temporarily, what the narrative is saying.

It is with this “poetic faith” that a listener/reader must accept the claim that the “mirror” has now become a “lake.” The dramatic effect is all important here in order to have the woman bending over the water to continue that search for herself.

The woman hopes to find “what she really is,” according to the mirror/lake. While the mirror might believe that the woman is searching for her real self, readers will grasp immediately that her obsession centers on her desire to hold on to her youth.

The mirror/lake then ridicules the woman for wanting to believe, “those liars,” that is, “the candles or the moon,” whose lighting can be deceptive, filling in those facial wrinkles, allowing her to believe that she does not look as old as she really does in the full light of day.

The mirror/lake has come to understand how important he is to the woman, despite her agitated reaction as she looks into that aging face. While he might expect gratitude for his faithful reporting, the mirror/lake does not seem to receive any thanks from the woman.

Yet despite not being thanked for his service, the mirror/lake takes satisfaction in knowing how important he has become to the woman. After all, she looks into the mirror/lake every day, no doubt, many times a day. Such attention cannot be interpreted any other way by the mirror: he is convinced of his vital rôle in the woman’s daily life.

As the woman depends on the mirror to report her aging development, the mirror/lake has come to depend on the woman’s presence before him. He knows that “her face” will continue to “replace[] the darkness” every morning.

The mirror/lake knows that whatever the woman takes away from his reflection every morning has become such an internal part of her life that he can count on her being there. He will never be alone but will continue to report his findings, objectively and truthfully. The mirror/lake’s final statement is one of the most profound statements to ultimatize a poem:

In me she has drowned a young girl, and in me an old woman

Rises toward her day after day, like a terrible fish.

Plath’s genius in fashioning a mirror that morphs into a lake allowed her to create these marvelous two final lines of her magnificent poem. If Sylvia Plath had produced nothing more than this poem, she would likely have become the great voice she is as a major twentieth-century poet.

No one can deny that a mirror becoming a lake is a stretch of the imagination that a in the hands of a less skillful wordsmith could have remained banal and even silly. But in the hands of a master poet that final two-line sentence grasps the mind of its readers/listeners. The genius of those lines delivers the poem into the natural world without one extraneous thought or word, rocking the world of literary studies.

🕉

You are welcome to join me on the following social media:

TruthSocial, Locals, Gettr, X, Bluesky, Facebook, Pinterest

🕉

Share