Image a: Robert Bly

Robert Bly’s Perversion of Translation

While his poems littered the literary landscape, the late Robert Bly tainted the art of translation. The man was both plagiarist and poetaster.

The Exacting Art of Translation

Translation is an exacting art, requiring knowledge of the target language as well as the language into which the work is to be translated. A modern plagiaristic scourge is tainting that art, and poetaster Robert Bly has remained a leading perpetrator of that scourge. Another egregious example is that of Ursula K. Le Guin, who purported to treat Lao Tsu’s Tao Te Ching.

To be fair to Le Guin, she does not label her work a “translation” and even admits that she does not read Chinese. But publishers, promoters, and reviewers often claim that the Le Guin treatment is a translation.

About the literary acumen of poetaster Robert Bly, critic and translator Eliot Weinberger has opined, “Robert Bly is a windbag, a sentimentalist, a slob in the language.” Describing much of the output of Bly’s drivel, Weinberger writes,

Not since Disney put gloves on a mouse has nature been so human: objects have “an inner grief”; alfalfa is “brave,” a butterfly “joyful,” dusk “half-drunk”; a star is “a stubborn man”; bark “calls to the rain”; “snow water glances up at the new moon.” It is a festival of pathetic fallacy. [1]

Weinberger is especially annoyed, however, that so many college students who hanker after becoming poets tend to choose Bly as their model. And they do so because “a Bly poem is so easy to write.” Unrestrained by technique, Bly engages “pointless and rarely believable metaphor (who else would compare the sound of a cricket to a sailboat?)”

Weinberger detects in Bly a “lack of emotional subtlety” that also likely attracts the immature minds of students. He suggests that Bly’s ability to write English has been “warped by reading too many bad translations.”

One might add that not only reading bad translations has warped Bly’s facility with the English language, but also his unsuccessful attempts to “translate” those works has warped the imaginations of other readers for decades.

For a significant part of Robert Bly’s literary career, the man has been “translating” the works of poets who write in Spanish, German, Swedish, Persian, Sanskrit, and other languages.

Bly, however, does not read, write, or understand any of the languages he supposedly “translates.” So the result of his so-called “translations” is simply revisions of the translations of others. According to Robert Richman,

Bly sought to revolutionize the art of translating poetry . . . Knowing the language well wasn’t the most important factor in translating poetry, Bly insisted, since “[w]hat you are essentially doing is slipping for a moment into the mood of the other poet. . . into an emotion which you may possibly have experienced at some time.”

In truth, Bly’s ideas about translation merely allowed the translator, as James Dickey put it, to take “as many liberties as [he] wants to take with the original, it being understood that this enables [him] somehow to approach the ‘spirit’ of the poem [he] is translating. [2]

Robert Bly takes a translation by someone who actually knows both the target language and English, who has actually translated the poem, changes some words, and calls his product a translation. An extended example of Bly’s fraudulent translation scheme is his publication titled The Kabir Book [3].

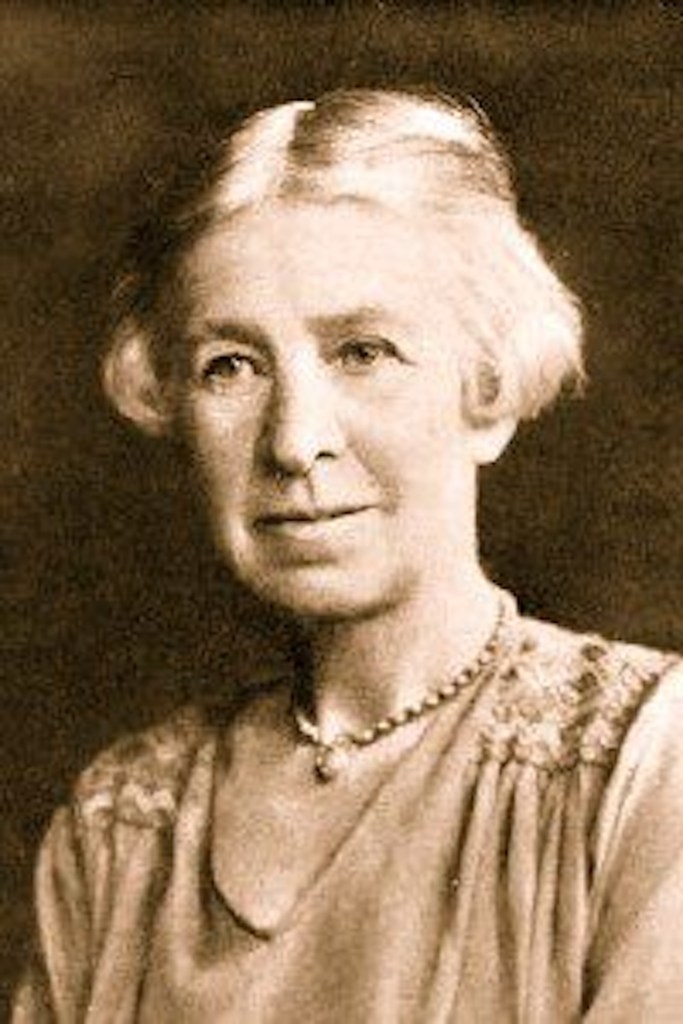

The poetaster revised forty-four of the genuine translations from One Hundred Poems of Kabir [4], by Rabindranath Tagore, Indian Nobel Laureate, and Evelyn Underhill, renowned spiritual writer and recipient of numerous honorary degrees. Bly would have his readers believe his revisions of the translations of these outstanding creative thinkers better represent Kabir. Bly’s folly leads him astray.

Image b: Rabindranath Tagore – Nobel Archive

Image c: Evelyn Underhill – Patheos

Tagore-Underhill’s Translations “Hopeless”

In Bly’s introduction to The Kabir Book, he claims that the Tagore-Underhill translations are “hopeless.” He does not explain what he means by “hopeless.” But he does claim that his purpose for re-translating some of the poems is to modernize them, put them into contemporary language.

However, he has attempted to fix that which was not broken. His claim that the Tagore translations are “hopeless” reveals part of the problem with Bly. If he found them “hopeless,” then obviously there is no way he could understand them well enough to improve on Tagore’s translations. Instead of merely modernizing the language, he loosens the diction, causing it to descend into a talky, laid-back kind of style that is not appropriate for its purpose.

The profound spiritual significance that these works have for the yogi-saint Kabir and his followers has been transformed into a libertine, 1960s-style free-love fest instead of the divine union of soul and God, as is their purpose. Because the poet Kabir was a God-realized saint, his poems and songs reflect the deep spiritual significance of his state of consciousness.

Kabir’s poems essentially perform two functions: the first is to express and describe the Ineffable [5] in words as nearly as possible through the saint’s devotion to God, and the second is to inspire and instruct his followers.

According to yogic philosophy [6] and training, the yogi who has succeeded in uniting his own soul with God has risen above all earthly, physical desires. Such a saint has only two desires left, and those two desires correspond to the above purposes ascribed to Kabir’s songs: to continue to enjoy union with God and to share it with others.

Image d: T. S. Eliot

T. S. Eliot Recognized the “Romantic Misunderstanding”

Western thinkers, philosophers, and poets such as W. B. Yeats, T. S. Eliot, and D. H. Lawrence have attempted to explain Eastern religion to the West. But T. S. Eliot noticed that he had great difficulty trying to understand Eastern philosophy. And Eliot admitted his difficulty and at the same time observed that what was passing as Eastern philosophical analysis was “romantic misunderstanding”:

And I came to the conclusion seeing also that the ‘influence’ of Brahmin and Buddhist thought upon Europe, as in Schopenhauer, Hartmann, and Deussen, had largely been through romantic misunderstanding . . . [7]

I suggest that this misunderstanding is evident in Bly’s version of the Tagore-Underhill translations. And because of the lack of understanding, Bly was unable to do what he claimed he was doing, making the poems more accessible to the modern reader.

Bly claims he had become fond of the “interiors” of the poems he chose to “translate,” but in reality his fondness rests on his own misunderstanding of what those “interiors” actually mean.

Contrasting Bly and Tagore-Underhill Translations

Robert Bly’s folly becomes apparent with the following “translation” from The Kabir Book:

Knowing nothing shuts the iron gates;

the new love opens them.

The sound of the gates opening wakes

the beautiful woman asleep.

Kabir says: Fantastic! Don’t let a

chance like this go by!

From One Hundred Poems of Kabir, the Tagore-Underhill translation follows:

The lock of error shuts the gate, open

it with the key of love:

Thus, by opening the door, thou shalt

wake the Belovèd.

Kabir says: ‘O brother! Do not pass

by such a good fortune as this.’

Bly’s version has transformed the meaning from God-union to human sexual copulation. Yogic philosophy claims that intense love for God awakens the soul and aids it in its search for God-union. The Tagore-Underhill translation has retained this spiritual significance.

“The lock of error” signifies the human’s mistaken belief that he is separate from God. Therefore, “love” opens the “gate” of separation. By opening the gate, the devotee awakens the soul to the “Belovèd”—capitalized because it refers to God.

Because the yogi’s goal is to awaken his desire for God, Kabir as the yogi-guru admonished his followers not to pass by such good fortune as can be found by unlocking his heart of love to God.

In Bly’s version, the poem promotes a human sexual opportunity. Few readers can pass by “iron gates” without their calling to mind Andrew Marvell’s “Coy Mistress.” And there is little doubt about what Marvell’s speaker was seeking with his coy mistress.

More importantly, “Belovèd” of the Tagore-Underhill version becomes in Bly’s “the beautiful woman asleep.” This kind of misrepresentation is a prototypical example of what T. S. Eliot meant when he claimed that Eastern influence on the West had come through “romantic misunderstanding.”

After transforming the Supreme Being into a beautiful woman, Bly has the yogi-saint cry: “Fantastic! Don’t let a change like this go by!” This mind-numbing act is an abomination, revealing an ignorance that would be funny if it were not so utterly misleading.

Bly’s Translation Career Based on Plagiarism

What Bly has actually accomplished in his “translation” career amounts to a large body of plagiarism of the original translators’ works. In addition to plagiarism instead of actual translation, Bly has misrepresented, distorted, and vulgarized the works of poets and translators, whose works he obviously has not understood.

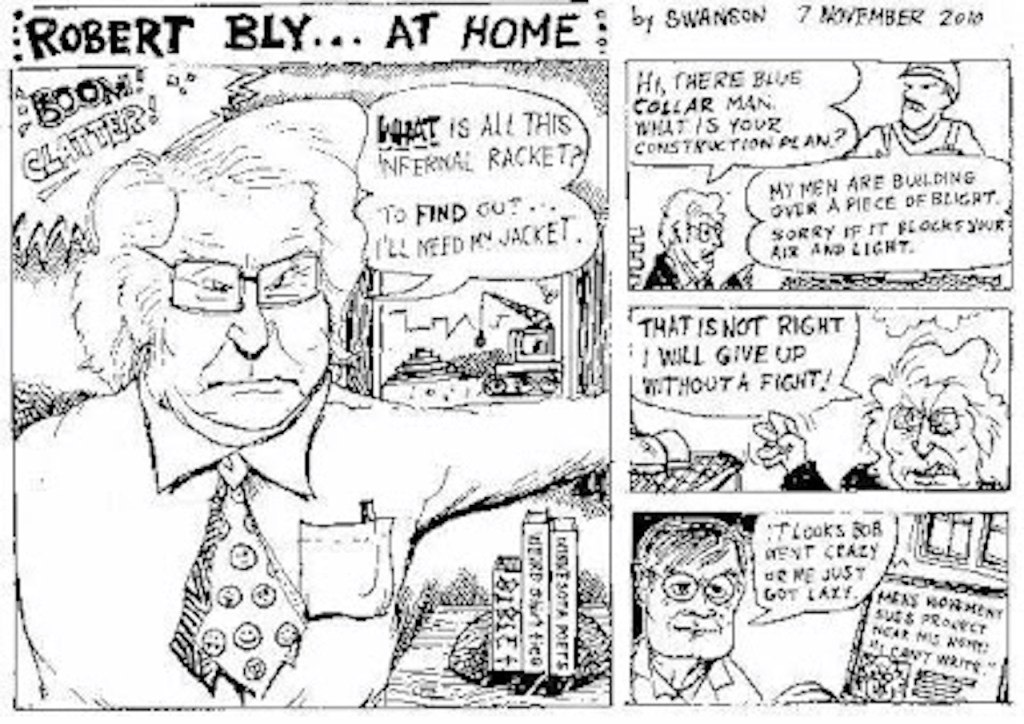

Bly once quipped that American readers “can’t tell when a man is counterfeiting and when he isn’t.” That Bly got away with his “counterfeiting” in the literary world is an disgrace and has damaged the art of literature in the minds and hearts of many readers for several decades. The poetaster’s counterfeiting of the art of translation may likely be his most egregious contribution to the bastardization of literary studies.

Nevertheless, Robert Bly continues to be lauded as a sacred cow of the literary world. Critics, scholars, and commentarians tend to shy away from offering any negative criticism of such individuals, lest their own reputation suffer. Therefore, the counterfeiting unfortunately continues long beyond its origin.

Sources

[1] Eliot Weinberger. “Gloves on a Mouse.” The Nation. Vol. 229, No. 16. November 17, 1979. Print. Also available on Enotes.

[2] Robert Richman. “The Poetry of Robert Bly.” The New Criterion. December 1986.

[3] Robert Bly. The Kabir Book. The Seventies Press. 1977. Print. Also available on Internet Archive.

[4] Rabindranath Tagore. One Hundred Poems of Kabir. Macmillan. London. 1970. Print. Also available on Internet Archive.

[5] Linda Sue Grimes. “Names for the Ineffable.” Linda’s Literary Home. November 10 2025.

[6] Paramahansa Yogananda. “Knowing God.” Self-Realization Fellowship. 2000.

[7] T. S. Eliot. After Strange Gods: A Primer on Modern Heresy. Farber. London. 1933. Print. Also available on Internet Archive.

Image f: Robert Bly Cartoon – New Age Pit Bull

Image g: Robert Bly is Struggling with Modernity

🕉

You are welcome to join me on the following social media:

TruthSocial, Locals, Gettr, X, Bluesky, Facebook, Pinterest

🕉

Share