Image: Symbolizing of the American Presidential Inaugural Poet – Created by Grok

Six Inaugural Doggerels

The tradition of presidential inaugural poetry in the United States, while relatively young, has become a significant cultural touchstone. However, a critical examination of these pieces reveals a troubling pattern of failure—with the notable exception of Robert Frost’s “The Gift Outright.”

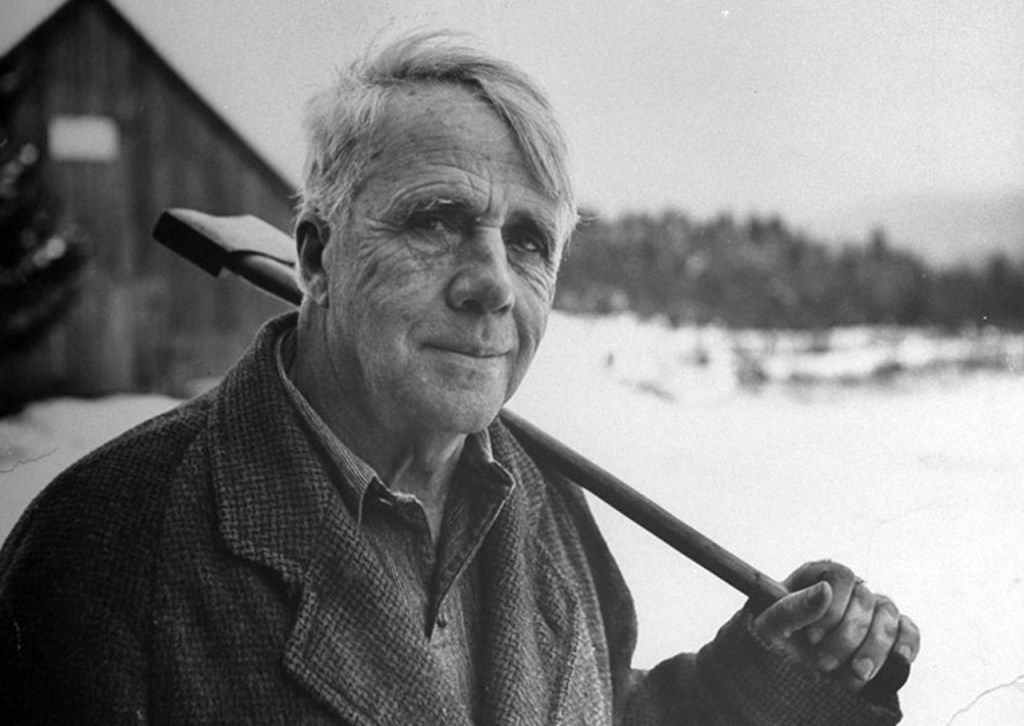

Robert Frost: “The Gift Outright” – January 20, 1961 (John F. Kennedy)

Robert Frost’s recitation of “The Gift Outright” at John F. Kennedy’s inauguration in 1961 stands as the pinnacle of inaugural poetry. Originally written in 1942, this poem was not specifically composed for the occasion, which definitely contributed to its success. Frost’s work masterfully encapsulates the American experience in just sixteen lines of iambic pentameter.

The poem’s strength lies in its ability to combine historical narrative with poetic artistry. Frost personifies the land as a feminine entity, creating a metaphorical relationship between the American people and their country. This personification allows Frost to explore complex themes of ownership, identity, and national destiny in a concise and powerful manner.

Critics have praised “The Gift Outright” for its technical proficiency and thematic depth. The poem’s conversational tone, coupled with its use of everyday speech, belies its sophisticated structure. Frost’s ability to create memorable phrases such as “vaguely realizing westward” and “unstoried, artless, unenhanced” demonstrates his mastery of language.

Furthermore, the poem’s division into two rhetorical halves allows Frost to present a nuanced view of American history. The first half explores the colonial period, while the second half delves into the nation’s growth and self-awareness. This structure enables Frost to create a narrative arc that resonates with the American experience.

However, the poet initially intended to preface his recitation of “The Gift Outright” with his new work “Dedication,” which he had composed especially for the occasion [1]. Critical analysis of the intended occasion piece reveals that it, too, succumbs to the same unfortunate level of failure and flaws that afflict the other pieces recited at American presidential inaugurations.

The Failures Following Frost

As Robert Bernard Hass has averred,

No American poet—not even Robert Frost—has written a good, let alone marginally acceptable inaugural poem. Puffed up with political pieties and generally employing coma-inducing, bureaucratic language, American inaugural poems lack the energy and insight of their authors’ best poems and, by and large, remain wholly forgettable. [12]

The subsequent inaugural poems following Frost—Maya Angelou’s “On the Pulse of Morning,” Miller Williams’ “Of History and Hope,” Elizabeth Alexander’s “Praise Song for the Day,” Richard Blanco’s “One Today,” and Amanda Gorman’s “The Hill We Climb”—have failed as literary works.

Literary critics and scholars have consistently highlighted their flaws: a tendency toward didacticism, lack of poetic depth, and an inability to transcend the occasional nature of their composition.

With the exception of Robert Frost’s “The Gift Outright,” these inaugural poems fail as poetry because of their subordination to political agendas, their stylistic weaknesses, and their critical rejection as art.

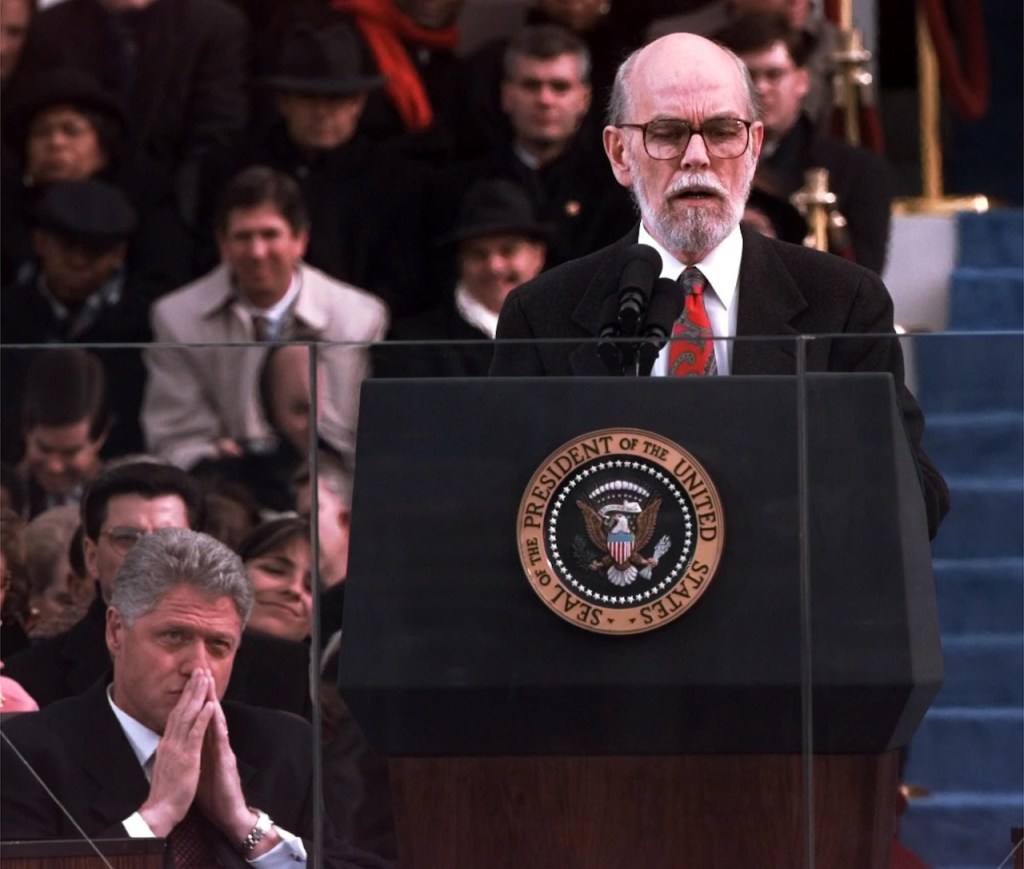

Maya Angelou: “On the Pulse of Morning” January 20, 1993 (Bill Clinton)

Maya Angelou’s “On the Pulse of Morning,” delivered at Bill Clinton’s first inauguration, exemplifies the pitfalls of occasional poetry when it prioritizes message over craft. The piece seeks to unify America by invoking natural symbols—a rock, a river, a tree—and tracing a hopeful arc from historical strife to communal renewal.

Yet, its ambition is undermined by what critics describe as a “preachy” tone and prosaic execution. Literary scholar Siobhan Phillips notes that Angelou’s work assumes a “racist ignorance” in its oversimplified narrative of American progress, glossing over complex histories with broad, sentimental strokes [2]. This didacticism sacrifices nuance for accessibility, a flaw that alienates the poem from the subtlety expected of great poetry.

Critics like Harold Bloom have been particularly harsh, arguing that “On the Pulse of Morning” lacks the linguistic rigor and imaginative leap of Angelou’s better prose works [3]. Its reliance on repetitive phrasing—”A Rock, A River, A Tree”—and predictable rimes* dilutes its impact, rendering it more sermon than song.

The Washington Post, covering the event, praised Angelou’s commanding delivery but sidestepped the poem’s literary merit, suggesting its success lay in performance, not text [4]. Such praise remains faint praise at best, and as Alexander Pope quipped: “Damn with faint praise, assent with civil leer, / And without sneering, teach the rest to sneer [5].”

Clinton’s decision to revive the inaugural poetry tradition aimed to signal cultural sophistication, yet the poem’s reception reveals a consensus: it fails to stand alone as art, tethered instead to the moment it was meant to embellish [6]. As Jay Parini observes, its “stuffy, pompous” quality reflects the inherent tension of poetry serving a public, political function.

Miller Williams: “Of History and Hope” January 20, 1997 (Bill Clinton)

Miller Williams’ “Of History and Hope,” recited at Clinton’s second inauguration, fares no better than Angelou’s under critical scrutiny. Intended as a meditation on America’s past and future, the poem employs a conversational tone and straightforward prosaic language: “We have memorized America, / how it was born and who we have been and where.”

While this accessibility aligns with the inaugural setting, it exposes the work’s primary flaw—its lack of poetic ambition. Critics argue that Williams sacrifices depth for clarity, producing a piece that feels more like a civics lesson than a literary creation.

Literary critic Marit MacArthur contends that the poem’s “loose unrhymed iambic pentameter” lacks the mastery Frost brought to the form, resulting in a “thin” and “uninspired” effort [4].

Its focus on collective memory and hope—”We mean to be the people we meant to be”—reads as platitudinous, failing to engage with the specific tensions of Clinton’s second term, such as political polarization or economic uncertainty.

The New York Times review of the inauguration noted Williams’ reading as a “quiet moment” but offered no praise for the poem itself, implying its forgettability, again reminiscent of Pope’s “faint praise.”

Scholar Jay Harvey [7] critiques its inability to address the presidential transition meaningfully, a failing shared by most inaugural poems but absent in Frost’s intended “Dedication,” which, though not delivered, aimed higher. Williams’ work, while earnest, collapses under its own simplicity, lacking the complexity or innovation to endure beyond its occasion.

Elizabeth Alexander: “Praise Song for the Day” January 20, 2009 (Barack Obama)

Elizabeth Alexander’s “Praise Song for the Day,” performed at Barack Obama’s first inauguration, promised a poetic reflection on daily American life amid historic change. Its opening lines—”Each day we go about our business, / walking past each other, catching each other’s eyes”—suggest a grounded, observational approach.

However, the poem quickly devolves into a catalogue of clichés and vague platitudes, earning it widespread critical disdain. Literary critics argue that its attempt to balance the mundane with the monumental results in a work that is neither profound nor memorable.

Helen Vendler, a prominent poetry critic, dismissed “Praise Song for the Day” as “prosaic and processional,” lacking the “imaginative leap” that distinguishes poetry from prose [1] . Its structure—a series of loosely connected vignettes—feels disjointed, and its language, such as “love with no need to preempt grievance,” is nothing more than sentimental abstraction.

The poem’s nod to Obama’s election as a transformative moment—”Say it plain: that many have died for this day”—is undercut by its failure to evoke specific emotion or imagery, a stark contrast to Frost’s vivid historical compression in “The Gift Outright.”

The Poetry Foundation’s coverage noted Alexander’s intent to capture a “public voice” but concluded that the result was “stilted” and overly cautious [2]. Critics agree that its reliance on generality over specificity renders it a poetic failure, overshadowed by the occasion it sought to elevate.

Richard Blanco: “One Today” January 21, 2013 (Barack Obama)

Richard Blanco’s “One Today,” delivered at Obama’s second inauguration, aimed to celebrate American diversity through a journey from dawn to dusk across the nation’s landscapes.

Its panoramic scope—spanning the Smoky Mountains to the Mississippi River—reflects an stilted inclusivity, particularly as the first inaugural poem by a Latino and purposefully openly gay poet. Thus this breadth comes at the cost of depth, and critics have panned its execution as overly descriptive and lacking in poetic resonance.

Scholar Natalie Bober critiques “One Today” for its “prosaic sprawl,” arguing that its litany of geographic and human details—”the empty desks of twenty children marked absent”—feels more like a travelogue than a poem [6]. The attempt to unify America under “one sun” and “one light” leans heavily on repetition but lacks the rhythmic or sonic sophistication to sustain it.

The Los Angeles Times praised Blanco’s personal story but found the poem itself “earnest but unremarkable” [4]. Compared to Frost’s taut 16 lines, Blanco’s expansive 80-line effort dilutes its impact, succumbing to what critic John Burnside calls the “outmoded triumphalist vision” of inaugural poetry [8]. Its critical reception underscores a recurring flaw: the inability to transcend the ceremonial context and achieve lasting literary value.

For my full commentary on this poem, please visit “Richard Blanco’s ‘One Today’.” (forthcoming)

Amanda Gorman: “The Hill We Climb” January 20, 2021 (Joe Biden)

Amanda Gorman’s “The Hill We Climb,” recited at Joe Biden’s inauguration, captured global attention with its youthful energy and timely references to the January 6 Capitol issue.

At 22, Gorman became the youngest inaugural poet, and her performance was widely celebrated for its charisma and optimism: “The new dawn blooms as we free it / For there is always light.” Yet, beneath the applause, literary critics have identified significant shortcomings that align it with its flawed predecessors rather than Frost’s exception.

Jay Harvey argues that “The Hill We Climb” fails to engage meaningfully with the presidency’s role or the specific challenges of Biden’s administration, opting instead for a “lofty appeal to our better selves” that skirts political substance [7].

Its heavy reliance on alliteration—”we’ve braved the belly of the beast”—and rimed couplets feels forced, prioritizing oral impact over textual depth. Critic Siobhan Phillips echoes this, noting that Gorman’s “global citizenship” rhetoric, while aspirational, lacks the historical grounding of Frost’s work, rendering it “shopworn” and detached from the occasion’s gravity [2].

The New Yorker lauded Gorman’s presence but critiqued the poem’s “unfinished” quality, mirroring her own metaphor for America but exposing its artistic limits [4]. Scholars agree that its success as a cultural moment overshadows its failure as a standalone poem, reinforcing the pattern of inaugural poetry’s literary inadequacy.

For my full commentary on this poem, please visit, Amanda Gorman’s “The Hill We Climb.” (forthcoming)

Graveyard for Poetic Ambition

Scholar A. R. Coulthard offers the following critique that perfectly encapsulates the flaws and failures of not only his target, Maya Angelou’s “On the Pulse of Morning,” but the other poets who have dared to share their wares at the American Presidential Inaugural ceremonies:

Polemical is almost always bad art because it assumes that worthy ideas are enough. Literary political crusaders who also honor the craft of their work, as Shelley did in some of his proletarian poems, are rare.

More typically, the dogma-driven poet pays insufficient heed to artistic demands, such as the excellent one expressed by the poet-priest Gerard Manley Hopkins when he defined poetry as “speech framed … to be heard for its own sake over and above its interest in meaning.”

The hack polemicist expects his or her words to soar on noble ideas rather than on the wings of poesy. “On the Pulse of Morning” perfectly exemplifies this attitude. [11]

Robert Frost’s “The Gift Outright” remains the gold standard for inaugural poetry, its 16 lines weaving a complex historical narrative with poetic precision that has weathered critical scrutiny.

Frost had intended to read “Dedication,” a longer, more explicit tribute to Kennedy’s administration, but glare from the sun and his own failing eyesight forced him to recite “The Gift Outright” from memory instead [1].

Frost inferior piece,”Dedication,” with its dense 80 lines and overly specific praise—”This is the day the Lord hath made”—was critiqued by Frost himself as less effective, yet its failure underscores the triumph of “The Gift Outright,” which distilled America’s essence without pandering.

In contrast, the works of Angelou, Williams, Alexander, Blanco, and Gorman—despite their moments of public acclaim—have been universally faulted by literary critics and scholars for their flaws: didacticism, lack of depth, and subservience to political spectacle. Such flaws devolves poetry into polemics, as described by Coulthard.

Frost’s poem, even when recited by necessity rather than choice, transcends its occasion; the others remain shackled to theirs. The tradition of inaugural poetry, while a noble gesture toward culture, reveals a persistent tension between art and utility.

As these critiques demonstrate, the poems’ failures stem not solely from their poets’ talents but from the impossible task of crafting lasting art under the weight of presidential expectation. Until a poet can match Robert Frost’s balance of craft and context, the inaugural stage will remain a graveyard for poetic ambition.

Sources

[1] Linda Sue Grimes. “Life Sketch of Robert Frost.” Linda’s Literary Home. Accessed December 3, 2025.

[2] Siobhan Phillips. “Political Poeticizing.” Poetry Foundation. July 01, 2015,

[3] Harold Bloom. The Best Poems of the Twentieth Century. HarperCollins. 1998. Print.

[4] Various Authors. Newspaper reviews from The Washington Post, The New York Times, and Los Angeles Times, cited in relevant inauguration coverage, 1993-2021.

[5] Alexander Pope. “Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot.” Poetry Foundation. Accessed March 3, 2025.

[6] Natalie Bober. A Restless Spirit: The Story of Robert Frost. Henry Holt. 1991. Print.

[7] James Harvey. “Of ‘Poetry and Power,’ Robert Frost and His Inaugural Successors.” Jay Harvey Upstage. January 31, 2021.

[8] John Burnside. The Music of Time: Poetry in the Twentieth Century. Princeton University Press. 2020. Print.

[11] A. R. Coulthard. “Poetry as Politics: Maya Angelou’s Inaugural Poem, ‘On the Pulse of Morning’.” Notes on Contemporary Literature. Vol. XXVIII. No. 1. January, 1999. pp. 2–5. Via eNotes. Accessed March 3, 2025.

[12] Robert Bernard Hass. “Praising Athenians in Athens: On the Failures of the American Ceremonial Poem.” Contemporary Poetry Review. May 7, 2013.

Commentaries on the Six Inaugural Doggerels

Image: Robert Frost Library of Congress

Robert Frost: The First American Inaugural Poet

Robert Frost had intended to preface his recitation of “The Gift Outright” with a recently created “Dedication,” but the sun rendered Frost’s reading impossible, so he dropped “Dedication” but continued on to recite “The Gift Outright” from memory.

Introduction with Text of “Dedication”

On January 20, 1961, Robert Frost became the first American poet to present a poem at a presidential inauguration. During the swearing-in of John F. Kennedy as the 35th president of the United States, Frost recited his poem, “The Gift Outright.” Although Frost had composed a new poem, “Dedication,” intended as a preface to his recitation of “The Gift Outright,” he had not committed it to memory in time for the ceremony.

At the inauguration, Frost attempted to read “Dedication” but was hindered by the intense sunlight reflecting off the snow, which obscured his view of the text. He managed to deliver the first 23 lines before abandoning the effort and transitioning to “The Gift Outright,” which he recited from memory [1]. While “Dedication” contains valuable historical insights, it also exhibits some of the exaggerated sentimentality that is often characteristic of occasional poetry [2].

Dedication

Summoning artists to participate

In the august occasions of the state

Seems something artists ought to celebrate.

Today is for my cause a day of days.

And his be poetry’s old-fashioned praise

Who was the first to think of such a thing.

This verse that in acknowledgement I bring

Goes back to the beginning of the end

Of what had been for centuries the trend;

A turning point in modern history.

Colonial had been the thing to be

As long as the great issue was to see

What country’d be the one to dominate

By character, by tongue, by native trait,

The new world Christopher Columbus found.

The French, the Spanish, and the Dutch were downed

And counted out. Heroic deeds were done.

Elizabeth the First and England won.

Now came on a new order of the ages

That in the Latin of our founding sages

(Is it not written on the dollar bill

We carry in our purse and pocket still?)

God nodded his approval of as good

So much those heroes knew and understood,

I mean the great four, Washington,

John Adams, Jefferson, and Madison

So much they saw as consecrated seers

They must have seen ahead what not appears,

They would bring empires down about our ears

And by the example of our Declaration

Make everybody want to be a nation.

And this is no aristocratic joke

At the expense of negligible folk.

We see how seriously the races swarm

In their attempts at sovereignty and form.

They are our wards we think to some extent

For the time being and with their consent,

To teach them how Democracy is meant.

“New order of the ages” did they say?

If it looks none too orderly today,

‘Tis a confusion it was ours to start

So in it have to take courageous part.

No one of honest feeling would approve

A ruler who pretended not to love

A turbulence he had the better of.

Everyone knows the glory of the twain

Who gave America the aeroplane

To ride the whirlwind and the hurricane.

Some poor fool has been saying in his heart

Glory is out of date in life and art.

Our venture in revolution and outlawry

Has justified itself in freedom’s story

Right down to now in glory upon glory.

Come fresh from an election like the last,

The greatest vote a people ever cast,

So close yet sure to be abided by,

It is no miracle our mood is high.

Courage is in the air in bracing whiffs

Better than all the stalemate an’s and ifs.

There was the book of profile tales declaring

For the emboldened politicians daring

To break with followers when in the wrong,

A healthy independence of the throng,

A democratic form of right divine

To rule first answerable to high design.

There is a call to life a little sterner,

And braver for the earner, learner, yearner.

Less criticism of the field and court

And more preoccupation with the sport.

It makes the prophet in us all presage

The glory of a next Augustan age

Of a power leading from its strength and pride,

Of young ambition eager to be tried,

Firm in our free beliefs without dismay,

In any game the nations want to play.

A golden age of poetry and power

Of which this noonday’s the beginning hour.

Commentary on “Dedication”

Robert Frost’s “Dedication,” while providing some insightful commentary, falls short of achieving the status of a genuine poetic work. Even when considered as an occasional poem, its final movement exhibits an excessive tendency towards hyperbolic adulation.

It is worth noting that the poem’s public recitation was ultimately prevented due to Frost’s inability to read it as planned [3]. This fortuitous circumstance may have inadvertently shielded the poet from potential criticism that likely would have ensued had the work been presented in its entirety. The glare of the sun, which impeded Frost’s ability to read the text, served to obscure this less successful composition from public scrutiny.

First Movement: Invocation to Artists

Summoning artists to participate

In the august occasions of the state

Seems something artists ought to celebrate.

Today is for my cause a day of days.

And his be poetry’s old-fashioned praise

Who was the first to think of such a thing.

This verse that in acknowledgement I bring

Goes back to the beginning of the end

Of what had been for centuries the trend;

A turning point in modern history.

The speaker appears to defer the task of transforming the inauguration into a grand and memorable event by emphasizing the value and relevance of artists’ contributions to such occasions.

He draws a parallel between his current endeavor and the historical tradition of “poetry’s old-fashioned praise,” suggesting that certain ceremonial moments inherently reflect broader historical patterns. The speaker’s assertions remain ambiguous and noncommittal, yet they leave room for the possibility of greater clarity and specificity as his discourse progresses.

He posits that his act of integrating verse into the event is rooted in an ancient tradition. However, he juxtaposes this notion with the phrase “the beginning of the end,” thereby hedging his position to account for potential criticism or failure.

This rhetorical strategy allows the speaker to simultaneously evoke a sense of timelessness while maintaining a degree of self-protection against possible counterarguments.

Second Movement: Forming a New Sovereign Nation

Colonial had been the thing to be

As long as the great issue was to see

What country’d be the one to dominate

By character, by tongue, by native trait,

The new world Christopher Columbus found.

The French, the Spanish, and the Dutch were downed

And counted out. Heroic deeds were done.

Elizabeth the First and England won.

The author presents a nuanced portrayal of colonial America, characterized by a complex interplay of European powers vying for supremacy in the New World. The narrative posits a critical question regarding which nation—France, Spain, or the Netherlands—would ultimately shape the nascent American identity.

However, the author resolves this query by asserting England’s ascendancy, attributing this triumph to Queen Elizabeth I. This pivotal development had far-reaching consequences for the cultural and linguistic landscape of the emerging nation. Consequently, the English language, rather than French, Spanish, or Dutch, became the predominant tongue of the New World.

Furthermore, one can infer that this English dominance extended beyond language to encompass broader cultural elements, including clothing preferences, social etiquette, and culinary traditions. While other European nations maintained a presence in the colonies, their influence was relegated to a secondary rôle in shaping the overarching colonial identity.

This perspective underscores the profound impact of England’s colonial success on the foundational characteristics of American society, highlighting the enduring legacy of early English settlements in molding the cultural fabric of the nation.

Third Movement: Tribute to the Founding Fathers

Now came on a new order of the ages

That in the Latin of our founding sages

(Is it not written on the dollar bill

We carry in our purse and pocket still?)

God nodded his approval of as good

So much those heroes knew and understood,

I mean the great four, Washington,

John Adams, Jefferson, and Madison

So much they saw as consecrated seers

They must have seen ahead what not appears,

They would bring empires down about our ears

And by the example of our Declaration

Make everybody want to be a nation.

The third movement, while containing historically accurate statements, exhibits structural inefficiencies that diminish its overall impact. The parenthetical remark “(Is it not written on the dollar bill / We carry in our purse and pocket still?)” followed by the assertion “God nodded his approval of as good” reduces the potency of the content. The phrase “Latin of our founding sages,” referring to “E Pluribus Unum” (Out of many, One), loses its significance when presented parenthetically.

Robert Frost’s religious views, characterized by agnostic tendencies, render the attribution of divine approval incongruous with his established persona, raising questions of authorial sincerity. This issue is further compounded by Frost’s secular interpretation of national founding principles, despite the historical significance of religious motivations in the nation’s establishment.

The poem’s nature as an occasional piece, composed to commemorate a politician’s ascension to office, further accentuates the problematic aspects of sincerity. However, the tribute to “Washington, / John Adams, Jefferson, and Madison” as “consecrated seers” remains an accurate historical characterization.

The concluding lines appropriately celebrate the Declaration of Independence, which, alongside the U.S. Constitution, represents one of the most significant texts in both American and global history. The enduring importance of these documents in inspiring national aspirations worldwide is accurately conveyed in the statement “our Declaration / Make everybody want to be a nation.”

Fourth Movement: Pursuing Natural Rights

And this is no aristocratic joke

At the expense of negligible folk.

We see how seriously the races swarm

In their attempts at sovereignty and form.

They are our wards we think to some extent

For the time being and with their consent,

To teach them how Democracy is meant.

“New order of the ages” did they say?

If it looks none too orderly today,

‘Tis a confusion it was ours to start

So in it have to take courageous part.

No one of honest feeling would approve

A ruler who pretended not to love

A turbulence he had the better of.

The author addresses the topic of immigration to the newly established nation. It is logical that individuals from various parts of the world would seek to emigrate from authoritarian regimes that suppress freedom in their countries of origin. Furthermore, it is reasonable that these individuals would desire to relocate to this newly formed nation.

This nascent nation, from its inception, embraces the principles of liberty and individual accountability, as enshrined in foundational documents that articulate the fundamental human rights of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The author refutes the notion that only the privileged class was valued and permitted to thrive in this new society.

Newly arrived immigrants may initially be considered wards of the state, but this status is temporary and contingent upon their consent. In essence, these immigrants have the opportunity to attain citizenship in this new land of freedom, as it embodies the concept of a “new order of the ages.”

Fifth Movement: The Courage of a Young Nation

Everyone knows the glory of the twain

Who gave America the aeroplane

To ride the whirlwind and the hurricane.

Some poor fool has been saying in his heart

Glory is out of date in life and art.

Our venture in revolution and outlawry

Has justified itself in freedom’s story

Right down to now in glory upon glory.

Come fresh from an election like the last,

The greatest vote a people ever cast,

So close yet sure to be abided by,

It is no miracle our mood is high.

Courage is in the air in bracing whiffs

Better than all the stalemate an’s and ifs.

The speaker then focuses on the very specific event of the Wright Brothers (“the twain”) and their new invention “the aeroplane.” He then asserts that such feats have put the lie to the “poor fool” who thinks that there is no longer any “glory” in “life and art.” He insists that the American adventure story in “revolution and outlawry” has been gloriously vindicated and “justified [ ] in freedom’s story.”

The speaker then offers his take of how this recent election, whose result he is now celebrating, played out. He deems it the “greatest vote a people ever cast”—an obvious exaggeration.

Yet, while the election was “close,” it will be “abided by.” The citizenry’s mood is “high,” and that fact is “no miracle.” He then asserts that such a situation arises out of the courage of the nation.

Sixth Movement: The Misfortune of the Inaugural Poem

There was the book of profile tales declaring

For the emboldened politicians daring

To break with followers when in the wrong,

A healthy independence of the throng,

A democratic form of right divine

To rule first answerable to high design.

There is a call to life a little sterner,

And braver for the earner, learner, yearner.

Less criticism of the field and court

And more preoccupation with the sport.

It makes the prophet in us all presage

The glory of a next Augustan age

Of a power leading from its strength and pride,

Of young ambition eager to be tried,

Firm in our free beliefs without dismay,

In any game the nations want to play.

A golden age of poetry and power

Of which this noonday’s the beginning hour.

The speaker subsequently directs attention to the specific accomplishment of the Wright Brothers, referred to as “the twain,” and their groundbreaking invention, the airplane. The author contends that such technological advancements refute the notion held by skeptics who believe that “life and art” no longer possess any inherent value or significance.

Furthermore, the speaker asserts that the American narrative of innovation and progress, characterized by “revolution and outlawry,” has been substantiated and validated within the context of the nation’s pursuit of freedom.

The speaker then provides an analysis of a recent electoral event, the outcome of which is being commemorated. While employing hyperbole, the speaker characterizes this election as the most significant democratic exercise in history.

Despite acknowledging the narrow margin of victory, the speaker emphasizes that the results will be respected. He notes the elevated morale of the citizenry, attributing this not to chance but to the inherent courage and resilience of the nation.

Robert Frost’s “The Gift Outright”

Robert Frost’s “The Gift Outright” became the first inaugural poem, read at John F. Kennedy’s swearing-in ceremony. This marked the first time a poet had participated in a presidential inauguration, setting a precedent for the inclusion of poetry in such events. The poet Robert Frost’s involvement, at Kennedy’s request, highlighted poetry’s cultural significance in American society.

Introduction with Text of “The Gift Outright”

On January 20, 1961, John F. Kennedy’s inauguration as the 35th president of the United States of America (35) took place. For this momentous occasion, Kennedy extended an invitation to America’s preeminent poet, Robert Frost, to compose and recite a poem.

Initially, Frost declined the proposition of crafting an occasional poem, prompting Kennedy to request a recitation of “The Gift Outright.” The poet acquiesced to this proposal. Kennedy then made an additional request of the venerable poet. He suggested altering the poem’s final line from “Such as she was, such as she would become” to “Such as she was, such as she will become.”

Kennedy believed this revision conveyed a more optimistic sentiment than Frost’s original. Though initially reluctant, Frost ultimately conceded to accommodate the young president’s wishes. Nevertheless, the poet did compose a poem specifically for the event, titled “Dedication,” intended as a prelude to “The Gift Outright.”

During the inauguration ceremony, Frost attempted to read the occasional poem. However, because of the intense sunlight reflecting off the snow, his aging vision was impaired, rendering the text illegible.

Consequently, the poet proceeded to recite “The Gift Outright” from memory. Regarding the alteration of the final line, rather than simply reciting Kennedy’s requested revision, Frost stated:

Such as she was, such as she would become, has become, and I – and for this occasion let me change that to –what she will become. (my emphasis added)

Thus, Frost maintained fidelity to his original vision while fulfilling the presidential request. “The Gift Outright” presents a concise historical narrative of the United States, which had just elected and was in the process of inaugurating its 35th president.

The speaker in the poem, without resorting to chauvinistic patriotism, manages to convey a positive perspective on the nation’s struggle for existence, framing it as a gift bestowed upon themselves and the world by the Founding Fathers.

In response to the query—”Well, Doctor, what have we got—a Republic or a Monarchy?”—regarding the outcome of the Constitutional Convention held from May 25 to September 17, 1787, in Philadelphia, Founding Father Benjamin Franklin replied, “A Republic, if you can keep it” [4].

The U.S. Constitution has proven to be an enduring gift. It supplanted the ineffectual Articles of Confederation and preserved the nation’s integrity even during the tumultuous Civil War nearly a century later.

The speaker in the poem offers a succinct overview of America’s struggle for existence, portraying this struggle and the resulting Constitution as a gift the Founders bestowed upon themselves and subsequent generations.

The Gift Outright

The land was ours before we were the land’s.

She was our land more than a hundred years

Before we were her people. She was ours

In Massachusetts, in Virginia,

But we were England’s, still colonials,

Possessing what we still were unpossessed by,

Possessed by what we now no more possessed.

Something we were withholding made us weak

Until we found out that it was ourselves

We were withholding from our land of living,

And forthwith found salvation in surrender.

Such as we were we gave ourselves outright

(The deed of gift was many deeds of war)

To the land vaguely realizing westward,

But still unstoried, artless, unenhanced,

Such as she was, such as she would become.

Robert Frost Reading “The Gift Outright”

At Inauguration

Commentary on “The Gift Outright”

Robert Frost’s inaugural poem offers a brief view into a slice of the history of the United States of America that has just elected its 35th president.

First Movement: The Nature of Possessing

The land was ours before we were the land’s.

She was our land more than a hundred years

Before we were her people. She was ours

In Massachusetts, in Virginia,

But we were England’s, still colonials,

Possessing what we still were unpossessed by,

Possessed by what we now no more possessed.

The speaker commences the initial movement by presenting an allusion to the historical context of the nation over which the newly appointed government official would now preside.

The speaker posits that the individuals who had established settlements on the territory, subsequently denominated as the United States of America, had initiated their endeavor in liberty while inhabiting the land that would eventually constitute their nation, and they would subsequently become its citizens.

Rather than merely existing as a loosely amalgamated collective of individuals, they would evolve into a unified citizenry sharing a common nomenclature and governance. The official date of inception for the United States of America is July 4, 1776; with the promulgation of the Declaration of Independence, the nascent nation assumed its position among the global community of nations.

The speaker accurately asserts that the land was in the possession of the populace “more than a hundred years” prior to the inhabitants attaining citizenship status within the country.

The speaker then references two significant early colonies, Massachusetts and Virginia, which would transition to statehood (commonwealths) following the cessation of English dominion over the new territory.

Second Movement: The Blessings of Law and Order

Something we were withholding made us weak

Until we found out that it was ourselves

We were withholding from our land of living,

And forthwith found salvation in surrender.

The period from 1776 to 1887 was characterized by the nascent United States’ endeavor to establish a governmental framework that would simultaneously safeguard individual liberties and institute a legal order conducive to life in a free society.

A significant initial step in this process was the formulation of the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union [5], the inaugural constitution drafted in 1777, which did not achieve ratification until 1781.

The Articles, however, proved inadequate in providing sufficient structure for the burgeoning nation. By 1787, it became apparent that a new, more robust document was necessary to ensure the country’s continued functionality and unity. Consequently, the Constitutional Convention of 1787 [6] was convened with the ostensible purpose of revising the Articles.

Rather than merely amending the existing document, the Founding Fathers opted to discard it entirely and draft a new U.S. Constitution. This document has remained the foundational set of laws governing the United States since its ratification on June 21, 1788 [7]. The struggle for effective self-governance in early America can be poetically described as “something we were withholding,” a reticence that “made us weak.”

Ultimately, the nation found “salvation in surrender,” as the Founding Fathers acquiesced to a document that not only provided legitimate order but also afforded the maximum possible scope for individual freedom. This compromise between structure and liberty has been a defining characteristic of the American governmental system since its inception.

Third Movement: The Blessing of Freedom

Such as we were we gave ourselves outright

(The deed of gift was many deeds of war)

To the land vaguely realizing westward,

But still unstoried, artless, unenhanced,

Such as she was, such as she would become.

The speaker characterizes the early, tumultuous history of the nation as a period marked by “many deeds of war,” referring to the conflict [8] in which early Americans engaged against England, their mother country, in pursuit of the independence they had both declared and demanded.

However, the nascent nation resolutely bestowed upon itself the “gift” of existence and liberty by persisting in its struggle and advancing through territorial expansion “westward.”

The populace endured numerous hardships—remaining “unstoried, artless, unenhanced”—as they persevered in their efforts to shape the nation into the powerful entity that, by the time of the poet’s recitation, had elected its 35th president.

Sources

[1] Tim Ott. “Why Robert Frost Didn’t Get to Read the Poem He Wrote for John F. Kennedy’s Inauguration.” Biography. June 1, 2020.

[2] Editors. “Occasional Poem.” American Academy of Poetry. Accessed March 4, 2025.

[3] Maria Popova. “On Art and Government: The Poem Robert Frost Didn’t Read at JFK’s Inauguration.” brainpickings. Accessed March 4, 2025.

[4] Editors. “Benjamin Franklin.” Respectfully Quoted: A Dictionary of Quotations. bartleby.com. Accessed March 4, 2025.

[5] Editors. “Articles of Confederation.” History. October 27, 2009.

[6] Richard R. Beeman. “The Constitutional Convention of 1787: A Revolution in Government.” Interactive Constitution. Accessed March 4, 2025..

[7] NCC Staff. “The Day the Constitution Was Ratified.” National Constitution Center. June 21, 2020.

[8] Curators. “Timeline of the Revolutionary War.” USHistory.org. Accessed March 4, 2025.

Image: Maya Angelou Reading at Clinton Inauguration People

Maya Angelou’s “On the Pulse of Morning”

Maya Angelou read her poem, “On the Pulse of Morning,” at Bill Clinton’s first inauguration, January 20, 1993. It was the first time a poem had been included in this ceremony since 1961, when aging poet Robert Frost plied his wares to celebrate John F. Kennedy’s swearing-in.

Introduction and Except from “On the Pulse of Morning”

Maya Angelou’s “On the Pulse of Morning,” recited at President Bill Clinton’s 1993 inauguration, is often lauded as a unifying emblem of American hope and resilience. However, a rigorous examination reveals it to be a flawed piece of discourse, displaying little more poetic skill or enduring value than a Hallmark card verse.

Its reliance on clichéd imagery, prosaic language, lack of structural sophistication, and over-dependence on its historical moment undermine its artistic merit, rendering it more a transient political gesture than a work of lasting poetry.

Poetaster Maya Angelou’s inaugural poem fails to rise above its occasion, and the occasional poem throughout history has proven to be the most difficult to pull off as a true piece of art.

On the Pulse of Morning

A Rock, A River, A Tree

Hosts to species long since departed,

Marked the mastodon,

The dinosaur, who left dried tokens

Of their sojourn here

On our planet floor,

Any broad alarm of their hastening doom

Is lost in the gloom of dust and ages.

But today, the Rock cries out to us, clearly, forcefully,

Come, you may stand upon my

Back and face your distant destiny,

But seek no haven in my shadow.

I will give you no hiding place down here.

You, created only a little lower than

The angels, have crouched too long in

The bruising darkness

Have lain too long

Face down in ignorance.

Your mouths spilling words

Armed for slaughter.

The Rock cries out to us today, you may stand upon me,

But do not hide your face.

Across the wall of the world,

A River sings a beautiful song. It says,

Come, rest here by my side.

Each of you, a bordered country,

Delicate and strangely made proud,

Yet thrusting perpetually under siege.

Your armed struggles for profit

Have left collars of waste upon

My shore, currents of debris upon my breast.

Yet today I call you to my riverside,

If you will study war no more. Come,

Clad in peace, and I will sing the songs

The Creator gave to me when I and the

Tree and the rock were one.

Before cynicism was a bloody sear across your

Brow and when you yet knew you still

Knew nothing.

The River sang and sings on.

There is a true yearning to respond to

The singing River and the wise Rock.

So say the Asian, the Hispanic, the Jew

The African, the Native American, the Sioux,

The Catholic, the Muslim, the French, the Greek

The Irish, the Rabbi, the Priest, the Sheik,

The Gay, the Straight, the Preacher,

The privileged, the homeless, the Teacher.

They hear. They all hear

The speaking of the Tree.

They hear the first and last of every Tree

Speak to humankind today. Come to me, here beside the River.

Plant yourself beside the River.

Each of you, descendant of some passed

On traveller, has been paid for.

You, who gave me my first name, you,

Pawnee, Apache, Seneca, you

Cherokee Nation, who rested with me, then

Forced on bloody feet,

Left me to the employment of

Other seekers—desperate for gain,

Starving for gold.

You, the Turk, the Arab, the Swede, the German, the Eskimo, the Scot,

You the Ashanti, the Yoruba, the Kru, bought,

Sold, stolen, arriving on the nightmare

Praying for a dream.

Here, root yourselves beside me.

I am that Tree planted by the River,

Which will not be moved.

I, the Rock, I the River, I the Tree

I am yours—your passages have been paid.

Lift up your faces, you have a piercing need

For this bright morning dawning for you.

History, despite its wrenching pain

Cannot be unlived, but if faced

With courage, need not be lived again.

Lift up your eyes upon

This day breaking for you.

Give birth again

To the dream.

Women, children, men,

Take it into the palms of your hands,

Mold it into the shape of your most

Private need. Sculpt it into

The image of your most public self.

Lift up your hearts

Each new hour holds new chances

For a new beginning.

Do not be wedded forever

To fear, yoked eternally

To brutishness.

The horizon leans forward,

Offering you space to place new steps of change.

Here, on the pulse of this fine day

You may have the courage

To look up and out and upon me, the

Rock, the River, the Tree, your country.

No less to Midas than the mendicant.

No less to you now than the mastodon then.

Here, on the pulse of this new day

You may have the grace to look up and out

And into your sister’s eyes, and into

Your brother’s face, your country

And say simply

Very simply

With hope—

Good morning.

Reading

Commentary on “On the Pulse of Morning”

Because this piece is so flawed, I have departed from my usual pattern of commenting on each movement or stanza. Instead, I have offered my critique engaging the main flaws and failures that I have encountered in this inaugural mediocrity.

It should come as no surprise that this poet, Dr. Maya Angelou, has put on display a piece of Hallmark quality verse that in no way rises the stature of a poem. For an in depth commentary on the true value of this poet, please visit my article “Dr. Maya Angelou: Sacred Cow of Po-Biz.”

While the late Ms. Angelou was a lovely woman and a truly motivational character, her talent for writing was meager at best and deplorable at worst. Yet, she cut a dashing figure and carved out for herself a remarkable cultural status. And despite the fact that she remains painfully undeserving of the adoration she continues to garner, one must begrudgingly admire and remain amazed by her stunning ability to to schmooze and bamboozle.

The Banality of Imagery

One of the most conspicuous weaknesses in “On the Pulse of Morning” is its dependence on imagery so commonplace that it lacks originality or depth. Angelou invokes natural symbols—the “Rock,” the “River,” and the “Tree”—as voices addressing humanity. While these elements aim to evoke a sense of timelessness and universality, their execution is so conventional that they reveal little more than banality.

A.R. Coulthard sharply observes that such symbols “are the stuff of greeting-card verse rather than serious poetry,” lacking the freshness or intricacy necessary to distinguish them as literary achievements [1].

For example, the Rock’s invitation to “Come, you may stand upon my / Back and face your distant destiny” feels less like a poetic vision and more like a recycled trope from inspirational literature, offering no new perspective or imaginative leap. This reliance on hackneyed imagery persists throughout the poem.

The River, described as flowing “past the cities and the towns,” and the Tree, standing “rooted in the earth,” present scenes so familiar they could adorn a mass-produced postcard. By contrast, poets like Robert Frost, in “The Road Not Taken,” transform ordinary natural imagery—two diverging paths—into a profound meditation on choice through subtle nuance and ambiguity.

Angelou’s symbols, however, remain static and predictable, their simplicity aligning more closely with the sentimental shorthand of Hallmark verses than with the layered resonance of canonical poetry.

The poem’s imagery also lacks the sensory richness that elevates poetic expression. Lines such as “The horizon leans forward, / Offering you space to place new steps of change” rely on abstract, visual platitudes rather than engaging the full spectrum of human perception—sound, touch, or smell—that poets like John Keats or Sylvia Plath wield to create vivid, memorable worlds.

This absence of texture reinforces the poem’s superficiality, rendering its natural motifs as decorative rather than transformative, much like the cursory illustrations accompanying a greeting card’s message.

The Prosaic Nature of Language

Beyond its imagery, “On the Pulse of Morning” falters in its linguistic execution, favoring a prosaic style over the compression and musicality that define poetic craft. Harold Bloom, a towering figure in literary criticism, has expressed reservations about Angelou’s broader poetic output, suggesting that it often prioritizes “moral uplift” over aesthetic rigor [2].

This inaugural poem’s language frequently resembles motivational rhetoric rather than art. Consider the lines “Lift up your eyes upon / The day breaking for you”: their straightforward, declarative tone lacks the metaphor, assonance, or rhythmic intricacy one might expect from a poet like T.S. Eliot, whose “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” weaves dense imagery and sound into a tapestry of meaning.

Angelou’s language often feels utilitarian, serving its immediate purpose without aspiring to the ambiguity or depth that distinguishes poetry from prose. For instance, the following lines read more like a self-help aphorism than a poetic utterance: “History, despite its wrenching pain, / Cannot be unlived, but if faced / With courage, need not be lived again.”

Its clarity and linearity leave little room for interpretation, a stark contrast to the enigmatic richness of Wallace Stevens’ “The Snow Man,” where language invites multiple readings.

Coulthard underscores this point, arguing that Angelou’s reliance on “prose-like simplicity” dilutes the poem’s claim to literary status [1]. This simplicity mirrors the directness of Hallmark card verses, which prioritize accessibility over artistry, offering comfort without intellectual or aesthetic challenge.

Moreover, the poem’s diction lacks the precision or inventiveness that might redeem its plainness. Words like “hope,” “change,” and “peace” recur without variation or redefinition, their overuse echoing the repetitive lexicon of commercial sentimentality.

Literary scholar Helen Vendler has critiqued contemporary poetry for its tendency to lean on “worn-out phrases” when it fails to innovate [3]. In “On the Pulse of Morning,” this tendency is evident, as Angelou’s language remains anchored in the familiar rather than forging new linguistic territory, further aligning it with the predictable cadences of greeting-card rhetoric.

Structural Weaknesses and Lack of Form

The poem’s structural deficiencies further compound its shortcomings, revealing a lack of formal discipline that undermines its poetic integrity. Spanning 106 lines, “On the Pulse of Morning” adopts a free-verse style but without the deliberate patterning or rhythmic coherence that elevates works like Walt Whitman’s “Miracles.”

Instead, its progression feels haphazard, more akin to a prose discourse interrupted by line breaks than a crafted poetic artifact. Coulthard notes that the poem’s “lack of structural unity” reflects its origins as an occasional piece, prioritizing its delivery over its permanence. This absence of form contrasts with the meticulous architecture of a sonnet by Shakespeare or a villanelle by Dylan Thomas, where structure enhances meaning.

The poem’s length, while ambitious, exacerbates its lack of cohesion. Lines meander without a clear arc or crescendo, as seen in the transition from the Rock’s address to the cataloguing of ethnic groups to the final call for unity.

This sprawling quality dilutes its impact, resembling a laundry list of ideas rather than a unified composition. Vendler argues that effective poetry, even in free verse, requires “an internal logic of form” to sustain its momentum [3]. Angelou’s poem, however, lacks such logic, its loose arrangement mirroring the brevity and lack of depth in the doggerel of amateurs, which similarly prioritize surface sentiment over structural sophistication.

Contextual Over-Dependence and Lack of Universality

Another critical flaw in “On the Pulse of Morning” is its over-reliance on its historical context, which restricts its ability to transcend the 1993 inauguration. Occasional poetry often ties itself to a specific moment, but the finest examples—such as Robert Frost’s “The Gift Outright” at Kennedy’s 1961 inauguration—achieve universality through timeless themes and linguistic innovation.

Angelou’s poem, by contrast, remains bound to the particulars of American history and Clinton’s political milieu. References to “the Asian, the Hispanic, the Jew” and “the Greek, the Irish, the Slav” feel like a roll call of diversity tailored to a 1990s audience, lacking the broader resonance that might speak to future generations. Coulthard contends that this specificity “anchors the poem too firmly in its immediate political milieu,” diminishing its potential as enduring art [1].

Harold Bloom’s broader critique of Angelou’s work amplifies this point. He suggests that her poetry often functions as “a gesture of social goodwill” rather than a contribution to the literary tradition, lacking the “agonistic struggle” that defines great art [2].

In “On the Pulse of Morning,” the “agonistic struggle” manifests as an absence of tension or complexity that might lift it beyond its occasion. The poem’s optimistic vision—”The day breaking for you”—presents a sanitized narrative of progress, sidestepping the darker ambiguities of human experience that poets like W.H. Auden explore in works such as “The Unknown Citizen.”

This lack of depth aligns it with the fleeting positivity of a Hallmark card, which similarly avoids challenging its audience in favor of temporary uplift. The poem’s failure to achieve universality is further evident in its inability to stand alone as a text.

Unlike Frost’s “The Gift Outright,” which retains its power independent of its inaugural context, Angelou’s work relies heavily on the spectacle of its delivery—her voice, the setting, the audience—to lend it weight.

Literary critic John Felstiner has noted that occasional poetry risks becoming “ephemeral” when it cannot “survive the page” [4]. The piece of doggerel “On the Pulse of Morning” exemplifies this ephemerality, its meaning tied to a moment rather than a lasting poetic vision, much like a greeting card’s message fades once its occasion passes.

Counterarguments and Rebuttal

Advocates of “On the Pulse of Morning” might argue that its accessibility and emotional appeal constitute its strength, particularly given its role in a public ceremony. The poem’s broad reach and its invocation of collective identity could be seen as virtues, reflecting Angelou’s stature as a voice for inclusivity. However, accessibility alone does not equate to poetic excellence.

As Vendler observes, “poetry that merely soothes risks losing its claim to art” [3]. The emotional simplicity of Angelou’s poem, while possibly effective as oratory, lacks the intellectual or aesthetic complexity that distinguishes poetry from prose or commercial verse. Its cultural significance as a historical artifact does not compensate for its literary deficiencies.

Furthermore, the poem’s reliance on its performative context does not excuse its textual weaknesses. Great poetry endures through its words, not its delivery. Shakespeare’s sonnets, for instance, require no stage to convey their power, whereas Angelou’s poem leans on external factors—her charisma, the inauguration’s gravitas—to mask its lack of intrinsic merit.

This unhealthy dependence reinforces its parallel to a Hallmark card, which similarly depends on its presentation through use of glossy paper, ribbons, or flamboyant visual imagery to enhance its otherwise vacuous content.

Placing Flawed Art on Display

Maya Angelou’s “On the Pulse of Morning” stands as a flawed piece of discourse, exhibiting little more poetic skill or value than a Hallmark card verse. Its clichéd imagery, prosaic language, structural weaknesses, and contextual over-dependence, as critiqued by Coulthard, Bloom, Vendler, and Felstiner, expose its artistic limitations. Actually, the piece is more qualified to be labeled doggerel than poetry.

While it fulfilled its role as an inaugural address, it lacks the originality, complexity, and universality required of significant poetry. Rather than a literary triumph, Angelou’s poem reflects the pitfalls of prioritizing occasion over craft, its lines echoing the transient sentimentality of greeting-card rhetoric rather than the enduring depth of true poetic art.

The ultimate calamity infused into the culture by these vacuous pieces of inauguration doggerel is that humanity suffers: sentimental, uplifting words decorated for an enhanced delivery cannot plumb the depths of the human heart and mind.

Would it not seem that such a momentous occasion as a presidential inauguration would demand the plumbing of those depths, instead of spoon feeding of sloppy sentimentality that continues to be offered up by these poetasters, pretending to be poets?

Sources

[1] A.R. Coulthard. “Poetry as Politics: Maya Angelou’s Inaugural Poem, ‘On the Pulse of Morning’.” Notes on Contemporary Literature, vol. XXVIII, no. 1, January 1999, pp. 2–5.

[2] Harold Bloom. The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages. Harcourt Brace. 1994. Print.

[3] HelenVendler. The Ocean, the Bird, and the Scholar: Essays on Poets and Poetry. Harvard University Press. 2015. Print.

[4] John Felstiner. Can Poetry Save the Earth?: A Field Guide to Nature Poems. Yale University Press. 2009. Print.

Image: Miller Williams – AZ Central

Miller Williams’ “Of History and Hope”

Like the other inaugural monstrosities that have gone on before and after, this effort by Miller Williams lacks the vision and skill required to rise to the level of a heartfelt, mind-challenging piece of art.

Introduction and Text of “Of History and Hope”

Miller Williams’ “Of History and Hope,” delivered at President Bill Clinton’s second inauguration in 1997, is frequently lauded as a work of unifying public verse. However, a close reading reveals that this flawed piece of discourse evinces scant poetic skill or aesthetic value beyond the level of a beginner’s doggerel.

Its structural disjunction, pedestrian diction, ineffectual deployment of poetic devices, and failure to transcend its narrowly occasional nature collectively undermine its artistic legitimacy.

Drawing upon the insights of scholars and critics such as Helen Vendler, Harold Bloom, Roger Kimball, and Daniel J. Flynn, this commentary exposes a work that demonstrably falters under rigorous scrutiny.

Of History and Hope

We have memorized America,

how it was born and who we have been and where.

In ceremonies and silence we say the words,

telling the stories, singing the old songs.

We like the places they take us. Mostly we do.

The great and all the anonymous dead are there.

We know the sound of all the sounds we brought.

The rich taste of it is on our tongues.

But where are we going to be, and why, and who?

The disenfranchised dead want to know.

We mean to be the people we meant to be,

to keep on going where we meant to go.

But how do we fashion the future? Who can say how

except in the minds of those who will call it Now?

The children. The children. And how does our garden grow?

With waving hands—oh, rarely in a row—

and flowering faces. And brambles, that we can no longer allow.

Who were many people coming together

cannot become one people falling apart.

Who dreamed for every child an even chance

cannot let luck alone turn doorknobs or not.

Whose law was never so much of the hand as the head

cannot let chaos make its way to the heart.

Who have seen learning struggle from teacher to child

cannot let ignorance spread itself like rot.

We know what we have done and what we have said,

and how we have grown, degree by slow degree,

believing ourselves toward all we have tried to become—

just and compassionate, equal, able, and free.

All this in the hands of children, eyes already set

on a land we never can visit—it isn’t there yet—

but looking through their eyes, we can see

what our long gift to them may come to be.

If we can truly remember, they will not forget.

Reading

Commentary on “Of History and Hope”

Far from representing a moment of poetic triumph, the piece emerges as a ceremonial footnote, its artistic merit scarcely exceeding that of a beginner’s doggerel—a missed opportunity on a significant national stage.

First Versagraph: Pattern of Deficiencies

We have memorized America,

how it was born and who we have been and where.

In ceremonies and silence we say the words,

telling the stories, singing the old songs.

We like the places they take us. Mostly we do.

The great and all the anonymous dead are there.

We know the sound of all the sounds we brought.

The rich taste of it is on our tongues.

But where are we going to be, and why, and who?

The disenfranchised dead want to know.

We mean to be the people we meant to be,

to keep on going where we meant to go.

This initial versagraph establishes a pattern of deficiencies, presenting a desultory structure and uninspired language that intimate a potential that remains unrealized. Helen Vendler posits that a poem’s form must embody a considered “process of thinking,” leading the reader through a discernible and coherent progression [1].

In this instance, however, Williams proffers a disconnected concatenation of elements—historical recapitulation (“We have memorized America”), ritualistic performance (“In ceremonies and silence”), and indeterminate questioning (“But where are we going to be, and why, and who?”)—lacking any discernible unifying principle.

The anaphoric deployment of “We” represents an attempt to forge a collective voice, but its iteration feels superficial, devoid of the rhythmic verve that Vendler celebrates in Whitman’s emphatic cadences [2]. Instead, it more closely resembles a prose oration segmented into lines, a neophyte’s error rather than a purposefully constructed poetic framework.

The diction further reveals a conspicuous absence of elevation. Lines such as “We like the places they take us. Mostly we do” are excessively colloquial, lacking the compression and capacity for surprise that Vendler ascribes to genuine poetic expression.

The metaphor of “the rich taste of it is on our tongues” gestures toward sensory engagement but remains resolutely abstract, lacking grounding in vivid imagery, unlike William Carlos Williams’ meticulously rendered “The Red Wheelbarrow.”

Harold Bloom might interpret this as an instance of “weak misreading” of the American poetic canon, a failure to grapple substantively with the historical gravity that the historical canon invokes [3].

The tautological effusion “We mean to be the people we meant to be” functions as a political bromide rather than a moment of poetic insight, aligning with Roger Kimball’s likely aversion to artistic expression diluted by populist sentiment (inferred from his cultural critiques) [4].

This versagraph, ostensibly intended to provide a foundational grounding for the poem, instead exposes a lack of capacity to establish either structural coherence or poetic richness.

Second Versagraph: Transition to Future

But how do we fashion the future? Who can say how

except in the minds of those who will call it Now?

The children. The children. And how does our garden grow?

With waving hands—oh, rarely in a row—

and flowering faces. And brambles, that we can no longer allow.

The second versagraph attempts to offer a transition to the future, yet its shortcomings are amplified, characterized by superficial use of poetic devices and thematic insipid blandness.

The deployment of rhetorical questions—”But how do we fashion the future? Who can say how”—aims for philosophical gravitas but remains underdeveloped, devolving into the banal repetition of “The children. The children.”

This reiteration, ostensibly intended for emphasis, feels contrived and maudlin, a far remove from the cumulative force that Vendler identifies in effective anaphora [2]. Tugging at heartstrings remains a dominant feature of political propaganda, not poetry.

The garden metaphor—”how does our garden grow? / With waving hands … and flowering faces”—offers a fleeting glimpse of potential imagery, yet its evocation of nursery-rime cadence (“Mary, Mary, quite contrary”) and reliance on the cliché of “flowering faces” compromise its originality. Bloom might view this as a feeble echo of more robust pastoral traditions, lacking genuine imaginative power.

Structurally, this versagraph fails to forge a substantive connection between past and future, a missed opportunity to enact the “montage in lieu of argument” that Vendler identifies as a strength in Yeats’ occasional verse.

Instead, it meanders, its allusion to “brambles” too imprecise to bear significant moral weight. Daniel J. Flynn might contend that this reflects a broader cultural predilection for comforting ambiguities over rigorous intellectual engagement, a characteristic flaw in amateur artistic endeavors (inferred from his commentary such as about Maya Angelou: she is “an author more revered than read”) [5].

The language maintains its prosaic character—”we can no longer allow”—lacking the requisite elevation to transmute its conceptual content into compelling poetry. This versagraph exemplifies doggerel’s proclivity to depend upon hackneyed tropes without refinement, revealing the limitations of Williams’ artistic skill.

Third Versagraph: Toward a Communal Credo

Who were many people coming together

cannot become one people falling apart.

Who dreamed for every child an even chance

cannot let luck alone turn doorknobs or not.

Whose law was never so much of the hand as the head

cannot let chaos make its way to the heart.

Who have seen learning struggle from teacher to child

cannot let ignorance spread itself like rot.

We know what we have done and what we have said,

and how we have grown, degree by slow degree,

believing ourselves toward all we have tried to become—

just and compassionate, equal, able, and free.

The third versagraph represents an attempt at a communal credo, yet its ponderous structure and reliance on sloganeering undermine its efficacy. The anaphoric pattern of “Who … cannot” is intended to generate rhetorical momentum, yet its predictability stifles the element of surprise that Vendler considers crucial to poetic effect. Each line delivers a moral truism—”cannot let ignorance spread itself like rot”—more appropriate to a political speech than to a poem.

The concluding list—”just and compassionate, equal, able, and free”—reads as a campaign slogan rather than a climactic moment of poetic insight, echoing Flynn’s likely critique of artistic expression subordinated to ideological concerns. This absence of subtlety aligns with Kimball’s skepticism toward cultural products that prioritize message over artistic craftsmanship.

The failed image of a personified entity called “luck”, exemplified in “luck alone turn doorknobs or not,” is quirky yet underdeveloped, failing to resonate as a compelling signal of opportunity.

Bloom might argue that this versagraph fails to engage substantively with the literary precursors it implicitly invokes—Whitman’s democratic vision or Dickinson’s incisive introspection—rendering it a superficial gesture.

Its structure, while exhibiting greater pattern than earlier versagraphs, remains fundamentally prosaic, with line breaks that appear arbitrary rather than rhythmically purposeful. This dependence on didacticism at the expense of artistry typifies a novice’s tendency to preach rather than explore, further solidifying the poem’s resemblance to doggerel.

Fourth Versagraph: Foundering on Sentimentality and Superficiality

All this in the hands of children, eyes already set

on a land we never can visit—it isn’t there yet—

but looking through their eyes, we can see

what our long gift to them may come to be.

If we can truly remember, they will not forget.

The concluding versagraph, intended to resolve the poem’s thematic concerns, instead founders on sentimentality and superficiality. The emphasis on children—”eyes already set / on a land we never can visit”—aims for poignancy but achieves only the level of cliché, a common pitfall of neophyte poetry.

Vendler observes that accomplished poets utilize such motifs to construct intricate montages, not to reiterate sentimental platitudes; Williams bland effort, however, offers no such complexity.

The phrase “it isn’t there yet” comes across as painfully prosaic, a dismissible line lacking any poetic force to elevate its vision. Bloom might dismiss this as a failure to confront the sublime, a retreat into banality rather than an act of poetic bravery.

The concluding line—”If we can truly remember, they will not forget”—promises a profound connection between memory and legacy yet delivers only a truism, its conditional structure unresolved. Kimball might view this as emblematic of the ephemerality of occasional verse, tethered to its specific historical context of 1997 without aspiring to enduring significance.

Structurally, this versagraph trails off into a weak conclusion, lacking the decisive cadence of an experienced poet. Its reliance on vague hope rather than substantive insight mirrors doggerel’s tendency to gesture toward depth without achieving it, thereby underscoring Williams’ technical and imaginative limitations.

Defending the Indefensible

Defenders of the poem might assert that its accessibility and optimistic tone are well-suited to its function as a public piece, with each versagraph contributing to a cohesive communal narrative.

The first versagraph establishes a historical context, the second and third bridge to the future, and the fourth links this trajectory to the concept of legacy. However, accessibility need not entail a sacrifice of artistic integrity—Whitman’s democratic voice achieves a synthesis of both through language innovation, while Williams’ execution ultimately falters, yielding banality rather than genuine resonance.

The motifs of “We” and “children,” while serving a unifying function, lack specificity, and the poem’s optimistic outlook feels generic rather than earned through the rigor of poetic exploration.

Its simplicity, perhaps intentionally cultivated according to Williams’ conception of poetry as “ordinary conversation and ritual” [6], lacks the requisite tension to effectively balance these poles, ultimately collapsing into prosaic laxity.

Vendler’s emphasis on the intrinsic relationship between form and substance reveals this purported restraint as a critical flaw rather than a virtue. And while Williams relationship with poetry may cover a reasonable number of year seemingly affording him “experience,” it is not the number of years of experiences that makes a great poet, or even good one; it is the quality of profound thought and the skill of execution that makes a truly memorable poet.

The Accumulation of Many Missteps

Miller Williams’ piece, “Of History and Hope,” examined across its four uneven versagraphs, reveals a consistent pattern of deficiencies: a structure characterized by aimless wandering rather than coherence, language that plods rather than soars, poetic devices that misfire rather than resonate, and thematic concerns that remain superficial in relation to the historical occasion that prompted the work.

Vendler and Bloom delineate the benchmarks of poetic excellence—coherent form, linguistic power, inventive thought—that Williams’ poem fails to meet, while Kimball and Flynn might contextualize its shortcomings within a broader cultural landscape that often privileges sentiment over genuine artistic substance.

Far from representing a moment of poetic triumph, the piece emerges as a ceremonial footnote, its artistic merit scarcely exceeding that of a beginner’s doggerel—a missed opportunity on a significant national stage.

Sources

[1] Helen Vendler. Poets Thinking: Pope, Whitman, Dickinson, Yeats. Harvard University Press.2006. Via Internet Archive. Accessed March 9, 2025.

[2] – – -. The Breaking of Style: Hopkins, Heaney, Graham. Harvard University Press, 1995. Via Internet Archive. Accessed March 9, 2025.

[3] Harold Bloom,. The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry. Oxford University Press, 1973. Via Internet Archive. Accessed March 9, 2025.

[4] Roger Kimball. “Rudyard Kipling: Unburdened.” The New Criterion. April 2008.

[5] Thomas Lifson. “Is It Time to Talk Honestly about Maya Angelou?” American Thinker. May 30, 2014.

[6] Miller Williams. Interview with Elizabeth Farnsworth. PBS NewsHour. 1997. Via “Miller Williams.” Poetry Foundation. Accessed March 9, 2025.

Image: Elizabeth Alexander Reading at Obama Inauguration Literary Kicks

Elizabeth Alexander’s “Praise Song for the Day”

Taking its place among other inaugural doggerel, Elizabeth Alexander’s “Praise Song for the Day” stumbles through 14 flailing movements, finishing with an empty single line displaying a cliché.

Introduction and Text of “Praise Song for the Day”

On January 20, 2009, at the history-making inauguration of the 44th Occupier of the Oval Office Barack Hussein Obama, Yale English professor Elizabeth Alexander delivered her piece, “Praise Song for the Day.”

Widely panned [1] by poets and critics alike—Carol Rumens writing in The Guardian finds the piece, “way too prosy”[2]—the piece features 14 erratic movements then tacks on the after-thought of a single-line flourishing a cliché.

Senior editor of The American Spectator, Tom Bethell [3], sums up the accurate critical position imposed by the vacuity of this inaugural piece:

I hesitate to call it a poem because it had so little connection to poetry as that art has been understood for centuries, indeed millennia. It was so dismal that the New York Times, in its 30-page special section the next day (“Full coverage of the inauguration of the 44th president”), failed to mention Alexander or print her poem. It had all the fizz of a week-old soda. No mention of it in the Washington Post either. What a decline there has been since Robert Frost’s performance at Kennedy’s inauguration in 1961.

As poet and literary critic Adam Kirsch [4], asserted, such a momentous occasion is “just the kind of event that might inspire genuine poetry.” However, as Kirsch continues, “the praetorian pomp, the Capitoline backdrop, the giant crowds, all seemed more redolent of Caesar than George Washington.” He asserts that Alexander’s failing to live up to the ancient standards of works delivered by such notables as Horace and Virgil was, however, “oddly heartening.”

Kirsch then explains: “In a monarchy, there is no shame for a poet, or for anyone else, in being the monarch’s servant. In our democratic age, however, poets have always had scruples about exalting leaders in verse.” Kirsch continues to elucidate the problem a poet faces in trying to write an occasional poem to feature at a presidential inauguration:

Since the French Revolution, there have been great public poems in English, but almost no great official poems. For modern lyric poets, whose first obligation is to the truth of their own experience, it has only been possible to write well on public themes when the public intersects, or interferes, with that experience—when history usurps privacy. (my emphasis)

Because the personal and the public must intersect, if the poem is to be successful, the fact that Alexander’s piece failed that intersection meant that the poem failed. Kirsch further explains that “Her verse is not public but bureaucratic—that is to say, spoken by no one and addressed to no one.” Thus, instead offering a genuine intersection of the personal and public, Alexander’s failed to be genuine because it “was a perfect specimen of this kind of bureaucratic verse.”

Praise Song for the Day

A Poem for Barack Obama’s Presidential Inauguration

Each day we go about our business,

walking past each other, catching each other’s

eyes or not, about to speak or speaking.

All about us is noise. All about us is

noise and bramble, thorn and din, each

one of our ancestors on our tongues.

Someone is stitching up a hem, darning

a hole in a uniform, patching a tire,

repairing the things in need of repair.

Someone is trying to make music somewhere,

with a pair of wooden spoons on an oil drum,

with cello, boom box, harmonica, voice.

A woman and her son wait for the bus.

A farmer considers the changing sky.

A teacher says, Take out your pencils. Begin.