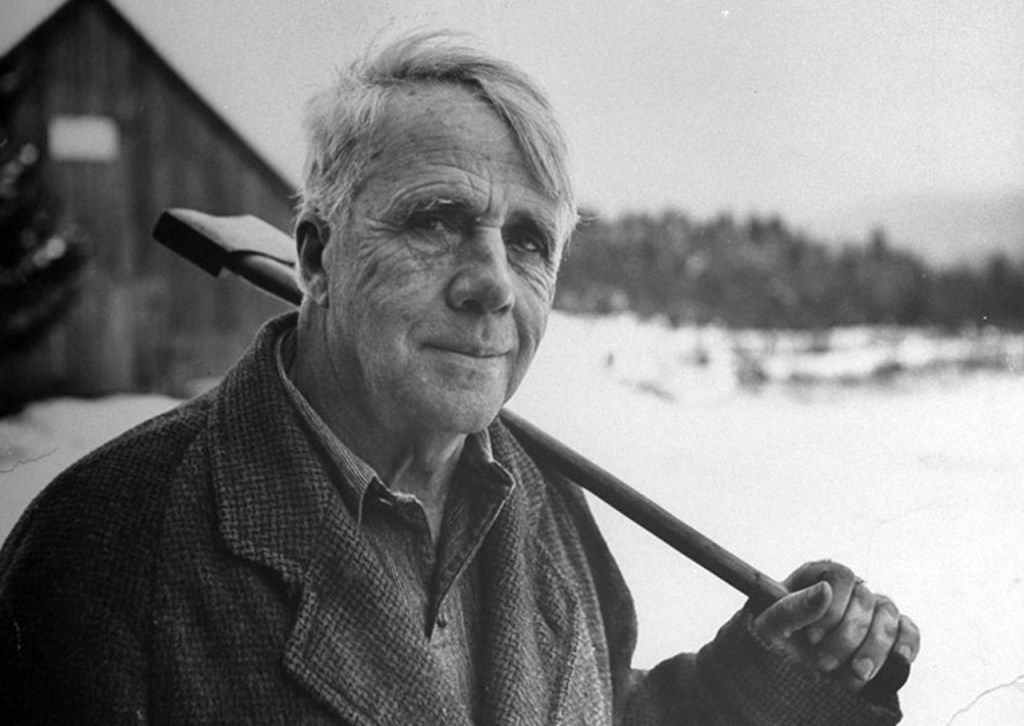

Image: Robert Frost – Library of America

The First American Inaugural Poet: Robert Frost

Robert Frost had intended to preface his recitation of “The Gift Outright” with a recently created “Dedication,” but the sun rendered Frost’s reading impossible, so he dropped “Dedication” but continued on to recite “The Gift Outright” from memory.

Introduction with Text of “Dedication”

On January 20, 1961, Robert Frost became the first American poet to present a poem at a presidential inauguration. During the swearing-in of John F. Kennedy as the 35th president of the United States, Frost recited his poem, “The Gift Outright.” Although Frost had composed a new poem, “Dedication,” intended as a preface to his recitation of “The Gift Outright,” he had not committed it to memory in time for the ceremony.

At the inauguration, Frost attempted to read “Dedication” but was hindered by the intense sunlight reflecting off the snow, which obscured his view of the text. He managed to deliver the first 23 lines before abandoning the effort and transitioning to “The Gift Outright,” which he recited from memory [1]. While “Dedication” contains valuable historical insights, it also exhibits some of the exaggerated sentimentality that is often characteristic of occasional poetry [2].

Dedication

Summoning artists to participate

In the august occasions of the state

Seems something artists ought to celebrate.

Today is for my cause a day of days.

And his be poetry’s old-fashioned praise

Who was the first to think of such a thing.

This verse that in acknowledgement I bring

Goes back to the beginning of the end

Of what had been for centuries the trend;

A turning point in modern history.

Colonial had been the thing to be

As long as the great issue was to see

What country’d be the one to dominate

By character, by tongue, by native trait,

The new world Christopher Columbus found.

The French, the Spanish, and the Dutch were downed

And counted out. Heroic deeds were done.

Elizabeth the First and England won.

Now came on a new order of the ages

That in the Latin of our founding sages

(Is it not written on the dollar bill

We carry in our purse and pocket still?)

God nodded his approval of as good

So much those heroes knew and understood,

I mean the great four, Washington,

John Adams, Jefferson, and Madison

So much they saw as consecrated seers

They must have seen ahead what not appears,

They would bring empires down about our ears

And by the example of our Declaration

Make everybody want to be a nation.

And this is no aristocratic joke

At the expense of negligible folk.

We see how seriously the races swarm

In their attempts at sovereignty and form.

They are our wards we think to some extent

For the time being and with their consent,

To teach them how Democracy is meant.

“New order of the ages” did they say?

If it looks none too orderly today,

‘Tis a confusion it was ours to start

So in it have to take courageous part.

No one of honest feeling would approve

A ruler who pretended not to love

A turbulence he had the better of.

Everyone knows the glory of the twain

Who gave America the aeroplane

To ride the whirlwind and the hurricane.

Some poor fool has been saying in his heart

Glory is out of date in life and art.

Our venture in revolution and outlawry

Has justified itself in freedom’s story

Right down to now in glory upon glory.

Come fresh from an election like the last,

The greatest vote a people ever cast,

So close yet sure to be abided by,

It is no miracle our mood is high.

Courage is in the air in bracing whiffs

Better than all the stalemate an’s and ifs.

There was the book of profile tales declaring

For the emboldened politicians daring

To break with followers when in the wrong,

A healthy independence of the throng,

A democratic form of right divine

To rule first answerable to high design.

There is a call to life a little sterner,

And braver for the earner, learner, yearner.

Less criticism of the field and court

And more preoccupation with the sport.

It makes the prophet in us all presage

The glory of a next Augustan age

Of a power leading from its strength and pride,

Of young ambition eager to be tried,

Firm in our free beliefs without dismay,

In any game the nations want to play.

A golden age of poetry and power

Of which this noonday’s the beginning hour.

Commentary on “Dedication”

Robert Frost’s “Dedication,” while providing some insightful commentary, falls short of achieving the status of a genuine poetic work. Even when considered as an occasional poem, its final movement exhibits an excessive tendency towards hyperbolic adulation.

It is worth noting that the poem’s public recitation was ultimately prevented due to Frost’s inability to read it as planned [3]. This fortuitous circumstance may have inadvertently shielded the poet from potential criticism that likely would have ensued had the work been presented in its entirety. The glare of the sun, which impeded Frost’s ability to read the text, served to obscure this less successful composition from public scrutiny.

First Movement: Invocation to Artists

Summoning artists to participate

In the august occasions of the state

Seems something artists ought to celebrate.

Today is for my cause a day of days.

And his be poetry’s old-fashioned praise

Who was the first to think of such a thing.

This verse that in acknowledgement I bring

Goes back to the beginning of the end

Of what had been for centuries the trend;

A turning point in modern history.

The speaker appears to defer the task of transforming the inauguration into a grand and memorable event by emphasizing the value and relevance of artists’ contributions to such occasions.

He draws a parallel between his current endeavor and the historical tradition of “poetry’s old-fashioned praise,” suggesting that certain ceremonial moments inherently reflect broader historical patterns. The speaker’s assertions remain ambiguous and noncommittal, yet they leave room for the possibility of greater clarity and specificity as his discourse progresses.

He posits that his act of integrating verse into the event is rooted in an ancient tradition. However, he juxtaposes this notion with the phrase “the beginning of the end,” thereby hedging his position to account for potential criticism or failure.

This rhetorical strategy allows the speaker to simultaneously evoke a sense of timelessness while maintaining a degree of self-protection against possible counterarguments.

Second Movement: Forming a New Sovereign Nation

Colonial had been the thing to be

As long as the great issue was to see

What country’d be the one to dominate

By character, by tongue, by native trait,

The new world Christopher Columbus found.

The French, the Spanish, and the Dutch were downed

And counted out. Heroic deeds were done.

Elizabeth the First and England won.

The author presents a nuanced portrayal of colonial America, characterized by a complex interplay of European powers vying for supremacy in the New World. The narrative posits a critical question regarding which nation—France, Spain, or the Netherlands—would ultimately shape the nascent American identity.

However, the author resolves this query by asserting England’s ascendancy, attributing this triumph to Queen Elizabeth I. This pivotal development had far-reaching consequences for the cultural and linguistic landscape of the emerging nation. Consequently, the English language, rather than French, Spanish, or Dutch, became the predominant tongue of the New World.

Furthermore, one can infer that this English dominance extended beyond language to encompass broader cultural elements, including clothing preferences, social etiquette, and culinary traditions. While other European nations maintained a presence in the colonies, their influence was relegated to a secondary rôle in shaping the overarching colonial identity.

This perspective underscores the profound impact of England’s colonial success on the foundational characteristics of American society, highlighting the enduring legacy of early English settlements in molding the cultural fabric of the nation.

Third Movement: Tribute to the Founding Fathers

Now came on a new order of the ages

That in the Latin of our founding sages

(Is it not written on the dollar bill

We carry in our purse and pocket still?)

God nodded his approval of as good

So much those heroes knew and understood,

I mean the great four, Washington,

John Adams, Jefferson, and Madison

So much they saw as consecrated seers

They must have seen ahead what not appears,

They would bring empires down about our ears

And by the example of our Declaration

Make everybody want to be a nation.

The third movement, while containing historically accurate statements, exhibits structural inefficiencies that diminish its overall impact. The parenthetical remark “(Is it not written on the dollar bill / We carry in our purse and pocket still?)” followed by the assertion “God nodded his approval of as good” reduces the potency of the content. The phrase “Latin of our founding sages,” referring to “E Pluribus Unum” (Out of many, One), loses its significance when presented parenthetically.

Robert Frost’s religious views, characterized by agnostic tendencies, render the attribution of divine approval incongruous with his established persona, raising questions of authorial sincerity. This issue is further compounded by Frost’s secular interpretation of national founding principles, despite the historical significance of religious motivations in the nation’s establishment.

The poem’s nature as an occasional piece, composed to commemorate a politician’s ascension to office, further accentuates the problematic aspects of sincerity. However, the tribute to “Washington, / John Adams, Jefferson, and Madison” as “consecrated seers” remains an accurate historical characterization.

The concluding lines appropriately celebrate the Declaration of Independence, which, alongside the U.S. Constitution, represents one of the most significant texts in both American and global history. The enduring importance of these documents in inspiring national aspirations worldwide is accurately conveyed in the statement “our Declaration / Make everybody want to be a nation.”

Fourth Movement: Pursuing Natural Rights

And this is no aristocratic joke

At the expense of negligible folk.

We see how seriously the races swarm

In their attempts at sovereignty and form.

They are our wards we think to some extent

For the time being and with their consent,

To teach them how Democracy is meant.

“New order of the ages” did they say?

If it looks none too orderly today,

‘Tis a confusion it was ours to start

So in it have to take courageous part.

No one of honest feeling would approve

A ruler who pretended not to love

A turbulence he had the better of.

The author addresses the topic of immigration to the newly established nation. It is logical that individuals from various parts of the world would seek to emigrate from authoritarian regimes that suppress freedom in their countries of origin. Furthermore, it is reasonable that these individuals would desire to relocate to this newly formed nation.

This nascent nation, from its inception, embraces the principles of liberty and individual accountability, as enshrined in foundational documents that articulate the fundamental human rights of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The author refutes the notion that only the privileged class was valued and permitted to thrive in this new society.

Newly arrived immigrants may initially be considered wards of the state, but this status is temporary and contingent upon their consent. In essence, these immigrants have the opportunity to attain citizenship in this new land of freedom, as it embodies the concept of a “new order of the ages.”

Fifth Movement: The Courage of a Young Nation

Everyone knows the glory of the twain

Who gave America the aeroplane

To ride the whirlwind and the hurricane.

Some poor fool has been saying in his heart

Glory is out of date in life and art.

Our venture in revolution and outlawry

Has justified itself in freedom’s story

Right down to now in glory upon glory.

Come fresh from an election like the last,

The greatest vote a people ever cast,

So close yet sure to be abided by,

It is no miracle our mood is high.

Courage is in the air in bracing whiffs

Better than all the stalemate an’s and ifs.

The speaker then focuses on the very specific event of the Wright Brothers (“the twain”) and their new invention “the aeroplane.” He then asserts that such feats have put the lie to the “poor fool” who thinks that there is no longer any “glory” in “life and art.” He insists that the American adventure story in “revolution and outlawry” has been gloriously vindicated and “justified [ ] in freedom’s story.”

The speaker then offers his take of how this recent election, whose result he is now celebrating, played out. He deems it the “greatest vote a people ever cast”—an obvious exaggeration. Yet, while the election was “close,” it will be “abided by.” The citizenry’s mood is “high,” and that fact is “no miracle.” He then asserts that such a situation arises out of the courage of the nation.

Sixth Movement: The Misfortune of the Inaugural Poem

There was the book of profile tales declaring

For the emboldened politicians daring

To break with followers when in the wrong,

A healthy independence of the throng,

A democratic form of right divine

To rule first answerable to high design.

There is a call to life a little sterner,

And braver for the earner, learner, yearner.

Less criticism of the field and court

And more preoccupation with the sport.

It makes the prophet in us all presage

The glory of a next Augustan age

Of a power leading from its strength and pride,

Of young ambition eager to be tried,

Firm in our free beliefs without dismay,

In any game the nations want to play.

A golden age of poetry and power

Of which this noonday’s the beginning hour.

The speaker subsequently directs attention to the specific accomplishment of the Wright Brothers, referred to as “the twain,” and their groundbreaking invention, the airplane. The author contends that such technological advancements refute the notion held by skeptics who believe that “life and art” no longer possess any inherent value or significance.

Furthermore, the speaker asserts that the American narrative of innovation and progress, characterized by “revolution and outlawry,” has been substantiated and validated within the context of the nation’s pursuit of freedom.

The speaker then provides an analysis of a recent electoral event, the outcome of which is being commemorated. While employing hyperbole, the speaker characterizes this election as the most significant democratic exercise in history.

Despite acknowledging the narrow margin of victory, the speaker emphasizes that the results will be respected. He notes the elevated morale of the citizenry, attributing this not to chance but to the inherent courage and resilience of the nation.

Image: Robert Frost – Library of Congress

Robert Frost’s “The Gift Outright”

Robert Frost’s “The Gift Outright” became the first inaugural poem, read at John F. Kennedy’s swearing-in ceremony. This marked the first time a poet had participated in a presidential inauguration, setting a precedent for the inclusion of poetry in such events. The poet Robert Frost’s involvement, at Kennedy’s request, highlighted poetry’s cultural significance in American society.

Introduction with Text of “The Gift Outright”

On January 20, 1961, John F. Kennedy’s inauguration as the 35th president of the United States of America (35) took place. For this momentous occasion, Kennedy extended an invitation to America’s preeminent poet, Robert Frost, to compose and recite a poem.

Initially, Frost declined the proposition of crafting an occasional poem, prompting Kennedy to request a recitation of “The Gift Outright.” The poet acquiesced to this proposal. Kennedy then made an additional request of the venerable poet. He suggested altering the poem’s final line from “Such as she was, such as she would become” to “Such as she was, such as she will become.”

Kennedy believed this revision conveyed a more optimistic sentiment than Frost’s original. Though initially reluctant, Frost ultimately conceded to accommodate the young president’s wishes. Nevertheless, the poet did compose a poem specifically for the event, titled “Dedication,” intended as a prelude to “The Gift Outright.”

During the inauguration ceremony, Frost attempted to read the occasional poem. However, because of the intense sunlight reflecting off the snow, his aging vision was impaired, rendering the text illegible.

Consequently, the poet proceeded to recite “The Gift Outright” from memory. Regarding the alteration of the final line, rather than simply reciting Kennedy’s requested revision, Frost stated:

Such as she was, such as she would become, has become, and I – and for this occasion let me change that to – what she will become. (my emphasis added)

Thus, Frost maintained fidelity to his original vision while fulfilling the presidential request. “The Gift Outright” presents a concise historical narrative of the United States, which had just elected and was in the process of inaugurating its 35th president.

The speaker in the poem, without resorting to chauvinistic patriotism, manages to convey a positive perspective on the nation’s struggle for existence, framing it as a gift bestowed upon themselves and the world by the Founding Fathers.

In response to the query—”Well, Doctor, what have we got—a Republic or a Monarchy?”—regarding the outcome of the Constitutional Convention held from May 25 to September 17, 1787, in Philadelphia, Founding Father Benjamin Franklin replied, “A Republic, if you can keep it” [4].

The U.S. Constitution has proven to be an enduring gift. It supplanted the ineffectual Articles of Confederation and preserved the nation’s integrity even during the tumultuous Civil War nearly a century later.

The speaker in the poem offers a succinct overview of America’s struggle for existence, portraying this struggle and the resulting Constitution as a gift the Founders bestowed upon themselves and subsequent generations.

The Gift Outright

The land was ours before we were the land’s.

She was our land more than a hundred years

Before we were her people. She was ours

In Massachusetts, in Virginia,

But we were England’s, still colonials,

Possessing what we still were unpossessed by,

Possessed by what we now no more possessed.

Something we were withholding made us weak

Until we found out that it was ourselves

We were withholding from our land of living,

And forthwith found salvation in surrender.

Such as we were we gave ourselves outright

(The deed of gift was many deeds of war)

To the land vaguely realizing westward,

But still unstoried, artless, unenhanced,

Such as she was, such as she would become.

Robert Frost Reading “The Gift Outright”

At Inauguration

Commentary on “The Gift Outright”

Robert Frost’s inaugural poem offers a brief view into a slice of the history of the United States of America that has just elected its 35th president.

First Movement: The Nature of Possessing

The land was ours before we were the land’s.

She was our land more than a hundred years

Before we were her people. She was ours

In Massachusetts, in Virginia,

But we were England’s, still colonials,

Possessing what we still were unpossessed by,

Possessed by what we now no more possessed.

The speaker commences the initial movement by presenting an allusion to the historical context of the nation over which the newly appointed government official would now preside.

The speaker posits that the individuals who had established settlements on the territory, subsequently denominated as the United States of America, had initiated their endeavor in liberty while inhabiting the land that would eventually constitute their nation, and they would subsequently become its citizens.

Rather than merely existing as a loosely amalgamated collective of individuals, they would evolve into a unified citizenry sharing a common nomenclature and governance. The official date of inception for the United States of America is July 4, 1776; with the promulgation of the Declaration of Independence, the nascent nation assumed its position among the global community of nations.

The speaker accurately asserts that the land was in the possession of the populace “more than a hundred years” prior to the inhabitants attaining citizenship status within the country.

The speaker then references two significant early colonies, Massachusetts and Virginia, which would transition to statehood (commonwealths) following the cessation of English dominion over the new territory.

Second Movement: The Blessings of Law and Order

Something we were withholding made us weak

Until we found out that it was ourselves

We were withholding from our land of living,

And forthwith found salvation in surrender.

The period from 1776 to 1887 was characterized by the nascent United States’ endeavor to establish a governmental framework that would simultaneously safeguard individual liberties and institute a legal order conducive to life in a free society.

A significant initial step in this process was the formulation of the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union [5], the inaugural constitution drafted in 1777, which did not achieve ratification until 1781.

The Articles, however, proved inadequate in providing sufficient structure for the burgeoning nation. By 1787, it became apparent that a new, more robust document was necessary to ensure the country’s continued functionality and unity. Consequently, the Constitutional Convention of 1787 [6] was convened with the ostensible purpose of revising the Articles.

Rather than merely amending the existing document, the Founding Fathers opted to discard it entirely and draft a new U.S. Constitution. This document has remained the foundational set of laws governing the United States since its ratification on June 21, 1788 [7]. The struggle for effective self-governance in early America can be poetically described as “something we were withholding,” a reticence that “made us weak.”

Ultimately, the nation found “salvation in surrender,” as the Founding Fathers acquiesced to a document that not only provided legitimate order but also afforded the maximum possible scope for individual freedom. This compromise between structure and liberty has been a defining characteristic of the American governmental system since its inception.

Third Movement: The Blessing of Freedom

Such as we were we gave ourselves outright

(The deed of gift was many deeds of war)

To the land vaguely realizing westward,

But still unstoried, artless, unenhanced,

Such as she was, such as she would become.

The speaker characterizes the early, tumultuous history of the nation as a period marked by “many deeds of war,” referring to the conflict [8] in which early Americans engaged against England, their mother country, in pursuit of the independence they had both declared and demanded.

However, the nascent nation resolutely bestowed upon itself the “gift” of existence and liberty by persisting in its struggle and advancing through territorial expansion “westward.”

The populace endured numerous hardships—remaining “unstoried, artless, unenhanced”—as they persevered in their efforts to shape the nation into the powerful entity that, by the time of the poet’s recitation, had elected its 35th president.

Sources

[1] Tim Ott. “Why Robert Frost Didn’t Get to Read the Poem He Wrote for John F. Kennedy’s Inauguration.” Biography. June 1, 2020.

[2] Editors. “Occasional Poem.” American Academy of Poetry. Accessed March 4, 2025.

[3] Maria Popova. “On Art and Government: The Poem Robert Frost Didn’t Read at JFK’s Inauguration.” brainpickings. Accessed March 4, 2025.

[4] Editors. “Benjamin Franklin.” Respectfully Quoted: A Dictionary of Quotations. bartleby.com. Accessed March 4, 2025.

[5] Editors. “Articles of Confederation.” History. October 27, 2009.

[6] Richard R. Beeman. “The Constitutional Convention of 1787: A Revolution in Government.” Interactive Constitution. Accessed March 4, 2025..

[7] NCC Staff. “The Day the Constitution Was Ratified.” National Constitution Center. June 21, 2020.

[8] Curators. “Timeline of the Revolutionary War.” USHistory.org. Accessed March 4, 2025.

🕉

You are welcome to join me on the following social media:

TruthSocial, Locals, Gettr, X, Bluesky, Facebook, Pinterest

🕉

Share