Image a: Illustration by Caroline Cracco

Who Speaks the Poem?

The speaker of a poem is seldom the poet. A poem is a dramatization similar to a play. The speaker is a created character, crafted by the poet to speak the message of the poem. Even when a poet shares sentiment with the speaker, they should be considered separate entities.

Poet and Speaker of a Poem: Seldom the

While referring to the speaker of a poem, it is always more accurate and safer to say, “the speaker” instead of “the poet” because the speaker of a poem is not always the poet. A poem is a crafted performance, a portrayal, or a dramatization similar to a play. The speaker is quite often a created character, just as the characters who are on display in a play are created characters. Most poets keep a heartfelt, sincere fondness for their poems.

They give in to no compunction about claiming the importance of their life experience, their personal goals, dreams, and heartfelt struggles that inform their poems. Quite frankly, poetry could not be created without such profound feelings and struggles experienced by the creators of poetry.

But poets quite often create characters through which to expresses that experience and those struggles. Thus, the safer answer to the question—”Who speaks the poem?”—is “the speaker speaks the poem.”

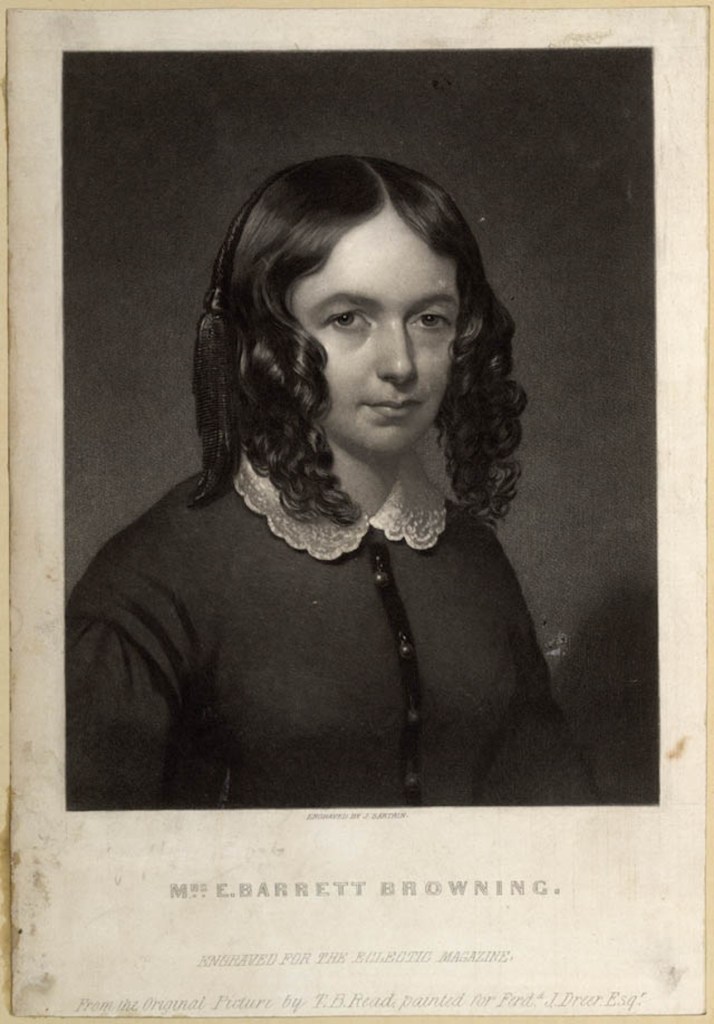

Image b: Elizabeth Barrett Browning – Library of Congress

Even if the speaker is obviously delving into her own feelings and situation, such as Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnets from the Portuguese, it remains more accurate to refer to the speaker of the poem as “the speaker” rather than “the poet,” “Elizabeth,” or “Barrett Browning.”

Speaking through Characters

Often poets may claim that their poems are their children; thus, it is important to keep in mind that children and their parents are not the same. Children may, and often do, hold very different ideas, beliefs and attitudes from those of their parents. A poem’s speaker may profess very different attitudes from the poet who wrote that speaker into existence—many times for that exact purpose.

Even though poets are close to their poems, they may not always place biographical information in their poems. Poets may not always reveal their exact beliefs in their poems. Like playwrights, poets usually create characters through which they speak in their poems.

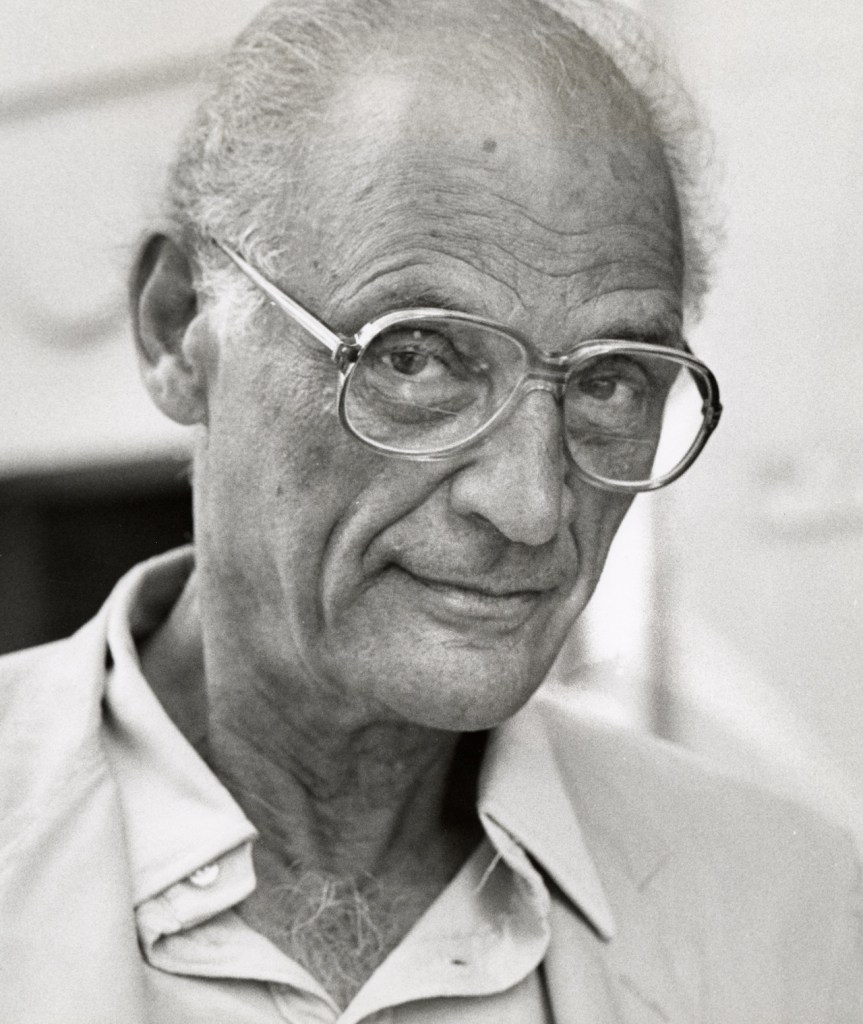

Image c: Arthur Miller

Readers are not likely to confuse the characters in a play with the playwright. Thus, no one would make the mistake of thinking that Willie Loman, the character in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, is Miller himself. Miller has explained that the Loman character is, in fact, based on the experiences of one of Miller’s uncles.

Image d: Langston Hughes – Carl Van Vechten – The New Yorker

Yet because Langston Hughes has written in his poem titled “Cross,” “My old man is a white old man / And my old mothers black,” readers often surmise that Langston Hughes himself had a white father and a black mother. Both of Hughes’ parents, however, were black. Hughes has created a character in his poem, just as Arthur Miller created Willie Loman in his play.

The Speaker’s Voice

While discussing a poem, the reader is always on more solid ground if he refers to the person vocalizing the words as “the speaker,” instead of “the poet.” A poet can give his character any ideas or beliefs that are necessary for the execution of the poem’s purpose. According to Anna Story, discussing this issue in “How to Tell Who the Speaker Is in a Poem,”

The speaker is the voice or “persona” of a poem. One should not assume that the poet is the speaker, because the poet may be writing from a perspective entirely different from his own, even with the voice of another gender, race or species, or even of a material object. [1]

In his poem “Cross,” Langston Hughes explores the idea of how an individual of mixed race might feel. So he created a mixed race character and let him speak. Hughes, himself, cannot be testifying as to how that person feels, because he does not actually have the experience himself. But he is perfectly capable of exploring the idea, the “what if” situation that poets engage in quite often.

A Caveat: Observation vs Inner Sturm und Drang

Langston Hughes’ “Cross” would likely have been a better poem had he not chosen to engage the first person. Some issues simply cry out for authenticity that speculation of this kind cannot provide.

Hughes’ message could have remained somewhat similar, but he would have avoided the twofold issue that he would be mistaken for a mixed race individual and that the plight of the speaker remains under a cloud of doubt.

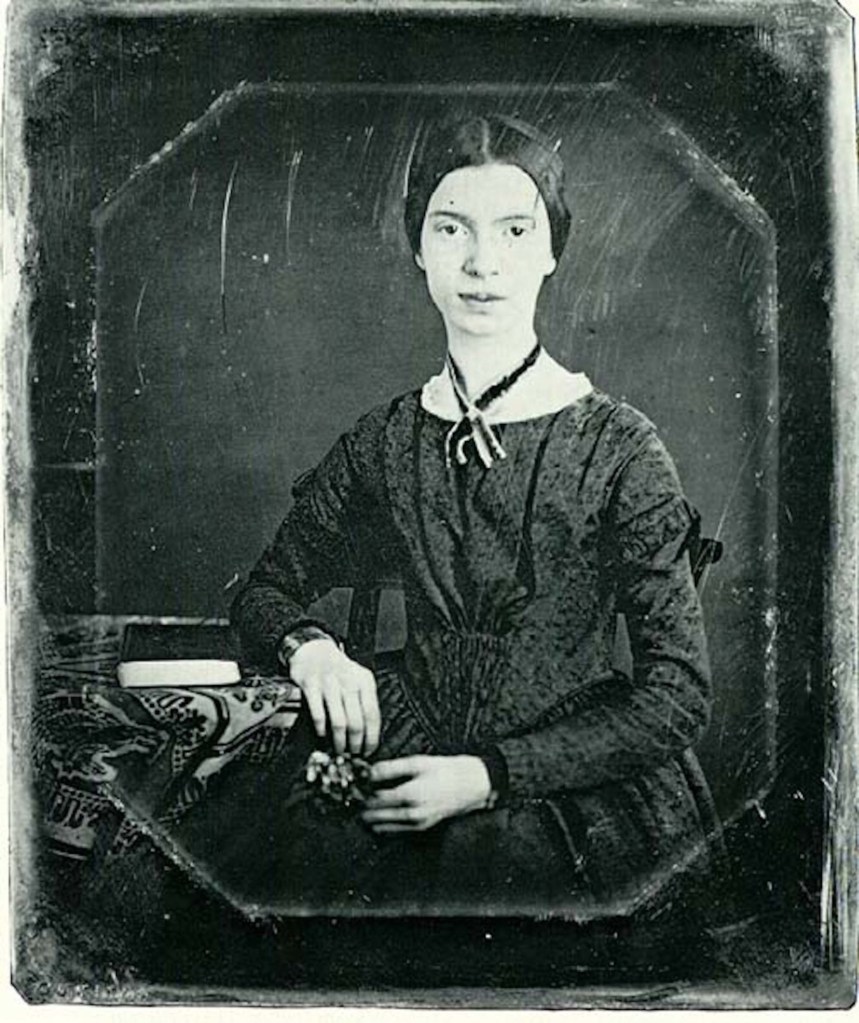

That fact does not detract from what other poets have achieved in their character creation. For example, Emily Dickinson assumes the persona of adult male to express the experience of “There’s been a Death, in the Opposite House,” and her portrayal remains genuine.

Unlike Hughes’ “Cross,” Dickinson’s speaker is reporting on an observation, not a deeply felt inner turmoil. Whether the speaker in Dickinson’s poem were a boy or a girl at the time of the observation matters very little, but if the poem had delved into deep seated feelings that the observation caused, it would have been less authentic to speak through the opposite sex.

Inner turmoil can be very differently experienced depending on the sex of the individual. As Paramahansa Yogananda has explained, females are guided more by feeling and males by reason; although both sexes possess both feeling and reason. In postlapsarian humanity, those qualities need to regain their balance and unity [2].

Exploration and Creativity

Poets, as well as novelists and playwrights, often explore feelings and thoughts and situations that they have not personally experienced. They often explore and dramatize beliefs that they do not necessarily hold.

For this reason, it is always safer to assume that the poet is creating a character rather than merely testifying, that he is exploring ideas rather than merely elaborating his own beliefs, thoughts, or feelings.Even though the poet may, in fact, be testifying and issuing her own beliefs, thoughts, or feelings, it is still more accurate and safer to assume that the poem is being spoken by a character, rather than by the poet.

Sources

[1] Anna Story. “How to Tell Who the Speaker Is in a Poem.” Pen & the Pad. Accessed January 6, 2026.

[2] Curators. “Spiritual Marriage.” Paramahansa Yogananda: The Royal Path of Yoga. January 6, 2026.

🕉

You are welcome to join me on the following social media:

TruthSocial, Locals, Gettr, X, Bluesky, Facebook, Pinterest

🕉

Share