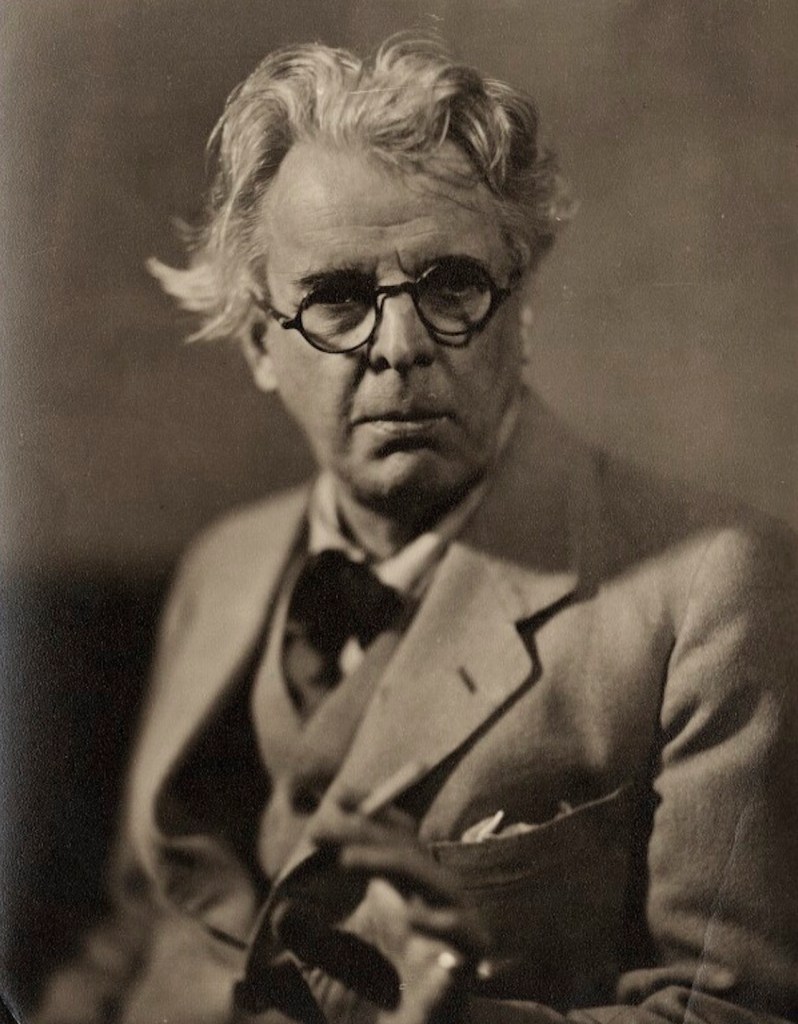

Image: William Butler Yeats NPG, London

Life Sketch of William Butler Yeats

William Butler Yeats possessed a lifelong dedication to the cultural and political rebirth of Ireland. He experienced life as a poet, playwright, and senator as he lived during turbulent shifts in Irish politics. He had a lifelong unquenchable thirst for artistic and spiritual truth.

William Butler Yeats remains one of the most influential literary figures of the modern era. His canon, which includes examples of his interest in Eastern philosophy, Irish folklore, and the vicissitudes of life, eventually resulted in the production of various literary forms such as poetry, drama, and essays [1].

Early Life and Education

Born on June 13, 1865, in Sandymount, County Dublin, William Butler Yeats was raised in a household that placed a high value on intellectual curiosity bolstered by cultural heritage.

His father, John Butler Yeats, was a skilled portrait painter, and his mother, Susan Pollexfen, created an environment steeped in Irish history and folklore. His early exposure to art, literature, and the stories of ancient Ireland instilled in Yeats a deep appreciation for myth and legend that would later become central themes in his work.

As a young man, Yeats attended the Metropolitan School of Art in Dublin, where he developed keen observational skills and his ability to capture what he saw into dramatic literary form such as poetry and plays.

His early attempts to write poetry were heavily influenced by Romanticism, and he found inspiration in the rich treasure house of Irish mythology and the natural world. These early experiences laid the groundwork for a lifelong exploration of the interplay between the tangible and the transcendent [2].

The Celtic Revival

In the 1880s and 1890s, Yeats became as a principal figure in the Celtic Revival—a cultural movement, aimed at reclaiming Ireland’s heritage from centuries of British domination.

Along with contemporaries such as Lady Gregory and Edward Martyn, Yeats sought to regain Irish identity through renewed interest and influence of its ancient myths and folklore. Yeats’ first poetry collections, including The Wanderings of Oisin and Other Poems (1889), offered a vision of Ireland as a land of fantastic beauty and heroic legend.

Yeats’ involvement in the Irish literary revival was not merely rhetorical and philosophical; he assisted in the founding of the National Literary Society and became a driving force behind the establishment of the Abbey Theatre, which became the center stage for modern Irish drama.

Through the Abbey Theatre, Yeats teamed up with playwrights and dramatists to stage works, combining Irish mythology with contemporary social and political issues; thus he became responsible for creating a distinctly Irish voice in the performing arts [3].

Changing Style and Interest in the Mysticism

As Yeats’ career progressed, his creative writings faced an important transformation. As he moved away from his early Romanticism, he took up themes of aging, disillusionment, and the search for spiritual meaning. This shift was influenced by his increasing interest in Eastern Philosophy and mystical traditions.

Yeats’ lifelong engagement with esoteric philosophy—ranging from Theosophy to the study of Eastern Philosophy—found expression in poems such as “The Second Coming” (1919) and “The Indian upon God” (1927). These works reflect a mind grappling with the decline of traditional values and the potential for rebirth through art and myth.

Yeats’ fascination with mysticism was not a mere intellectual exercise; it became deeply personal. He was a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, an organization dedicated to the study and practice of magical rituals and mysticism.

This involvement influenced his poems with symbolic imagery and complex mythological references that continue to captivate readers. The cyclical view of history that Yeats espoused—wherein civilizations rise, decay, and ultimately transform—became a recurring theme of his later work.

Unfortunately, Yeats’ study of Eastern Philosophy/Religion at times led him astray. Some of his works demonstrated that he failed to understand [4] the most important aspects of the concepts that he tried to portray in his poems.

While his poem “The Indian upon God” accurately reflects Eastern tenets, his “The Second Coming” and “Lapis Lazuli” go far astray. The bulk of his understanding of Eastern philosophical and religious concepts may be described no less than by the term assigned by T. S. Eliot “romantic misunderstanding.”

Politics and the Poet in Society

The early twentieth century was a period of political upheaval in Ireland, and Yeats became increasingly involved with the nationalist movement. Even though he never fully aligned himself with any particular political party, his writings and public statements often reflected a profound concern for the fate of his country. His poetry became the main medium through which he expressed hope but also anxiety about the future of his country.

Poems such as “Easter 1916” suggest that whatever happens no one can deny that those rebels will have died for their dreams. This speaker still cannot completely commit to those dreams. All he can admit is that everything has changed and “A terrible beauty is born.”

The Yeatsian musing of drama ultimately finds only that things have changed. The speaker cannot say if they have changed for better for worse. He and his generation will have to wait to see how that “terrible beauty” matures. However, this duality—of destruction and creation—reflects the eternal cycles that he so frequently explored in his verse.

Beyond his poetry, Yeats contributed directly to the political life of his nation. He served from 1922-1928 in the senate of the newly formed Irish Free State [5]. Although he was often seen as an outsider by both traditional nationalists and modernists, Yeats’ presence in the Senate suggested a belief in the vital role that artists and intellectuals play in shaping public discourse and guiding cultural evolution.

Image b: Yeats and Gonne

Personal Life and Love

Yeats’ personal life was distressed by a long, unrequited love for Maud Gonne [6], an Irish revolutionary and actress. His feelings for Gonne inspired many of his poems, imbuing them with themes of love, loss, and longing. Gonne’s rejection of his marriage proposals did not deter Yeats from writing some of his most passionate poetry, where she often appears as a muse or an ideal.

Later in life, Yeats married Georgie Hyde-Lees, who not only became his companion but also a collaborator in his mystical explorations. They had two children, Anne and Michael, and their family life was documented in some of Yeats’ more personal poems, such as “A Prayer for My Daughter” and “The Circus Animals’ Desertion.”

The Alignment of Myth and Modernity

A central aspect of Yeats’ enduring appeal is his ability to weave together disparate strands of experience—myth and modernity, beauty and decay, hope and despair—into a coherent vision of the human condition. His poetry often reads as if it were both a dream and a prophecy, a blend of personal reflection and universal truth.

For instance, in “Sailing to Byzantium,” Yeats contrasts the ephemeral nature of the physical world with the possibility of spiritual transcendence [7]. The poem’s vivid imagery and rhythmic cadence invite readers to contemplate the eternal in the midst of the temporal, a duality that lies at the heart of Yeats’ artistic endeavor.

Yeats’ engagement with myth was not limited to the realm of poetry; it also informed his political and cultural projects. By reviving ancient Irish legends and traditions, he sought to restore a sense of identity and continuity to a country grappling with the forces of modernity and colonialism. His poem “The Fisherman” offers an example of this engagement.

His work with the Abbey Theatre was driven by the conviction that drama rooted in myth could foster a national spirit and provide a counterpoint to the homogenizing effects of globalization. In this way, Yeats not only redefined the poetic landscape but also contributed to a broader cultural renaissance in Ireland.

An Enduring Influence on Literature and Beyond

The influence of William Butler Yeats extends far beyond the confines of his own time. His exploration of spiritual and metaphysical themes paved the way for subsequent generations of poets and writers who sought to reconcile the material and the mystical. In the decades following his death, critics and scholars have revisited his work, probing its layers of symbolism and historical context to uncover new meanings and insights.

Contemporary literary critics often highlight the innovative structure and language of Yeats’ later poetry, noting how his use of recurring symbols and motifs creates a dense network of associations that invites endless interpretation.

His ability to encapsulate the complexities of Irish identity, the ravages of time, and the interplay between art and life continues to resonate in today’s discussions of literature and culture.

Moreover, Yeats’ political engagement and his belief in the transformative power of art have inspired not only writers but also activists and cultural leaders who view the arts as a vital force for social change [8].

That political engagement, however, begs for a caveat. As postmodernism crept ever nearer the hearts of the contemporary artists, the loss of skill and lack of interest in truth began to blight both poetry and criticism. That postmodern mind-set has little hope of heralding and power to transform society for the better.

Yeats’ Legacy

William Butler Yeats’ life and work remain a testament to the power of art to illuminate the deepest mysteries of existence. From his early days steeped in Irish folklore to his later explorations of mystical symbolism and political transformation, he navigated the tumultuous currents of change with a keen and reflective mind. His ability to articulate the paradoxes of beauty and decay, hope and despair, has left an indelible mark on the world of literature.

Yeats’ legacy is a reminder that art is not merely a reflection of life but also can serve as an agent of transformation, when steeped in desire for truth. His vision of history as a series of cyclic renewals, his embrace of the occult and the mythical, and his commitment to cultural and political renewal have all contributed to a body of work that continues to inspire and challenge readers. In celebrating Yeats, one celebrates the eternal quest for meaning—a quest that, like his poetry, transcends time and place.

Through his poetic innovations and his fervent commitment to the rebirth of Irish culture, William Butler Yeats carved out a unique space in the annals of literary history. His words continue to echo in classrooms, theaters, and the hearts of those who dare to dream beyond the confines of the everyday routine.

Death

In his later years, Yeats’ poetry grew increasingly reflective and introspective. The themes of mortality, the nature of artistic creation, and the inexorable passage of time became ever more emphasized.

Works such as The Tower (1928) and The Winding Stair and Other Poems (1933) reveal a man deeply aware of his own aging and the inevitable approach of death. Yet, even as he grappled with the transient nature of human life, he remained committed to the idea that art could capture eternal truths.

Despite experiencing poor health, Yeats continued to write and speak out on matters of art, politics, and philosophy until his final days. On the French Riviera, he spent his last months in quiet musing, as he sought solace and reflection away from the public eye.

On January 28, 1939, in Menton, France, [9] William Butler Yeats passed away peacefully . The world mourned not just the passing of a literary giant, but also the departure of a visionary who had continually challenged and enriched the cultural landscape of Ireland and beyond.

One of the most profound memorial poems to Yeats is W. H. Auden’s “In Memory of W. B. Yeats.” The following excerpt contains some of the poem’s most memorable lines, for example, “Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry”:

You were silly like us; your gift survived it all:

The parish of rich women, physical decay,

Yourself. Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry.

Now Ireland has her madness and her weather still,

For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

In the valley of its making where executives

Would never want to tamper, flows on south

From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs,

Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives,

A way of happening, a mouth.

Sources

[1] Richard Ellmann,. Yeats. New York. Oxford University Press, 1989.

[2] Mark Fryer,. The Life of W.B. Yeats: A Critical Biography. London. Bloomsbury Academic. 2001.

[3] A. Norman Jeffares. The Cambridge Companion to W.B. Yeats. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

[4] Linda S. Grimes. “William Butler Yeats’ Transformations of Eastern Religious Concepts.” Ball State University. PhD Dissertation. 1987.

[5] Editors. “W. B. Yeats: Irish Author and Poet.” Britannica. Accessed February 22, 2025.

[6] Lisa Fortin Jackson. “Great Irish Romances: W.B. Yeats and Maud Gonne.” Wild Geese. February 4, 2014.

[7] C. S. Lieber. The Collected Works of W.B. Yeats. New York. Knopf. 1963.

[8] William Butler Yeats. The Collected Poems of W.B. Yeats. Edited by Richard J. Finneran, New York. 2009.

[9] Editors. “William Butlet Yeats.” Biography. August 17, 2020.

Commentaries on Yeats Poems

🕉

You are welcome to join me on the following social media:

TruthSocial, Locals, Gettr, X, Bluesky, Facebook, Pinterest

🕉

Share