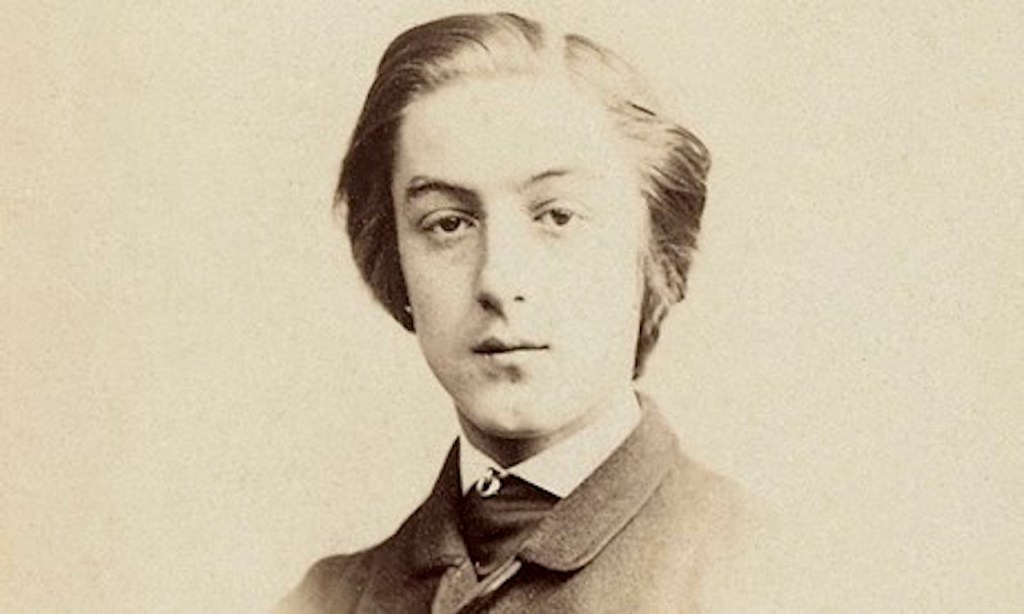

Image: Gerard Manley Hopkins

Life Sketch of Gerard Manley Hopkins

Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–1889) was a poet of exceptional originality, with an innovative approach to language. He remains one of English literature’s most enigmatic figures—a poet-priest whose work combines Victorian sensibilities with modernist experimentation.

Introduction: Early Life and Family Background

Though Gerard Manley Hopkins work was largely unpublished during his lifetime, the poet is now celebrated as one of the most significant poets of the Victorian era and a precursor to modernist poetry.

His life was marked by a profound tension between his religious vocation as a Jesuit priest and his artistic calling as a poet, a tension that shaped both his personal struggles and his creative achievements.

Gerard Manley Hopkins was born on July 28, 1844, in Stratford, Essex (now part of Greater London), into a middle-class family with strong artistic and religious inclinations. He was the oldest of nine children born to Manley Hopkins and Catherine Smith Hopkins.

His father was a successful marine insurance adjuster, who also wrote poetry and published works such as A Philosopher’s Stone and Other Poems (1843) [1]. His mother Catherine was deeply religious and musically gifted, fostering an environment where intellectual and artistic pursuits were encouraged [2].

The Hopkins household emphasized education and creativity. Gerard’s siblings also displayed artistic talents: his brother Arthur became an illustrator for Punch magazine, while another brother Everard pursued his calling to architecture [3]. The family’s Anglican faith played a central role in their lives; Gerard’s early exposure to religious devotion would later profoundly influence his poetry.

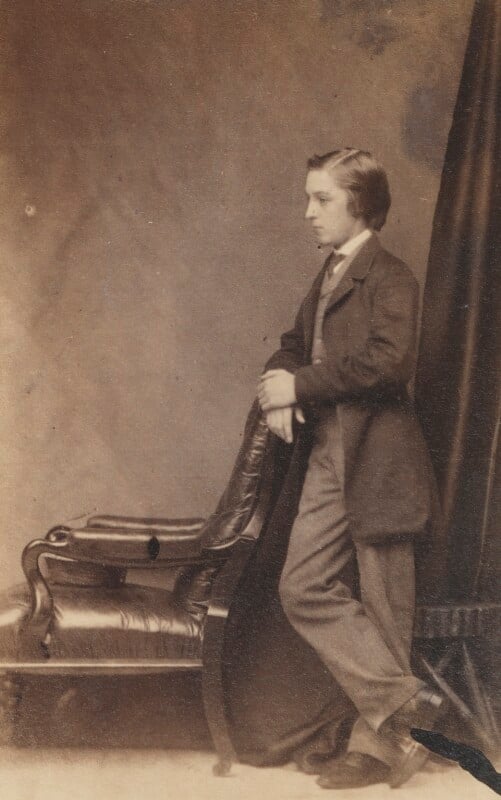

Image: Gerard Manley Hopkins

Education at Highgate School

In 1854, at the age of ten, Hopkins began attending Highgate School in London, where he excelled academically and demonstrated his early poetic talent. His school years were marked by a deep engagement with Romantic poetry, particularly the works of John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley. Keats’s lush imagery and musicality left a lasting impression on the young poet, as can be seem in some of his earliest compositions.

While at Highgate, Hopkins also developed an interest in drawing and painting. He considered pursuing art as a career before ultimately deciding to focus on literature. While his early poems from this period reflect the Romantic tradition, they also hint at the originality that would later define his mature work [4].

The Oxford Years: Intellectual Growth and Conversion

In 1863, Hopkins entered Balliol College, Oxford, where he studied the Classics. Oxford in the mid-19th century was a hub of intellectual ferment, particularly regarding questions of faith and theology.

The Oxford Movement, led by figures such as John Henry Newman, sought to revive Catholic elements within Anglicanism [5]. This movement profoundly influenced Hopkins during his time at the university.

At Balliol, Hopkins excelled academically and formed lasting friendships with notable contemporaries such as Robert Bridges (later Poet Laureate of England). Bridges would play a crucial role in preserving and publishing Hopkins’s poetry after his death. During this period, Hopkins continued writing poetry but also began engaging with questions of faith that would lead to a dramatic transformation of his life

In 1866, under the influence of Newman’s writings and teachings, Hopkins converted to Roman Catholicism. This decision caused significant tension in his family, all of whom were devout Anglicans. However, for Hopkins, the conversion represented a profound spiritual awakening that would shape both his personal life and his artistic vision.

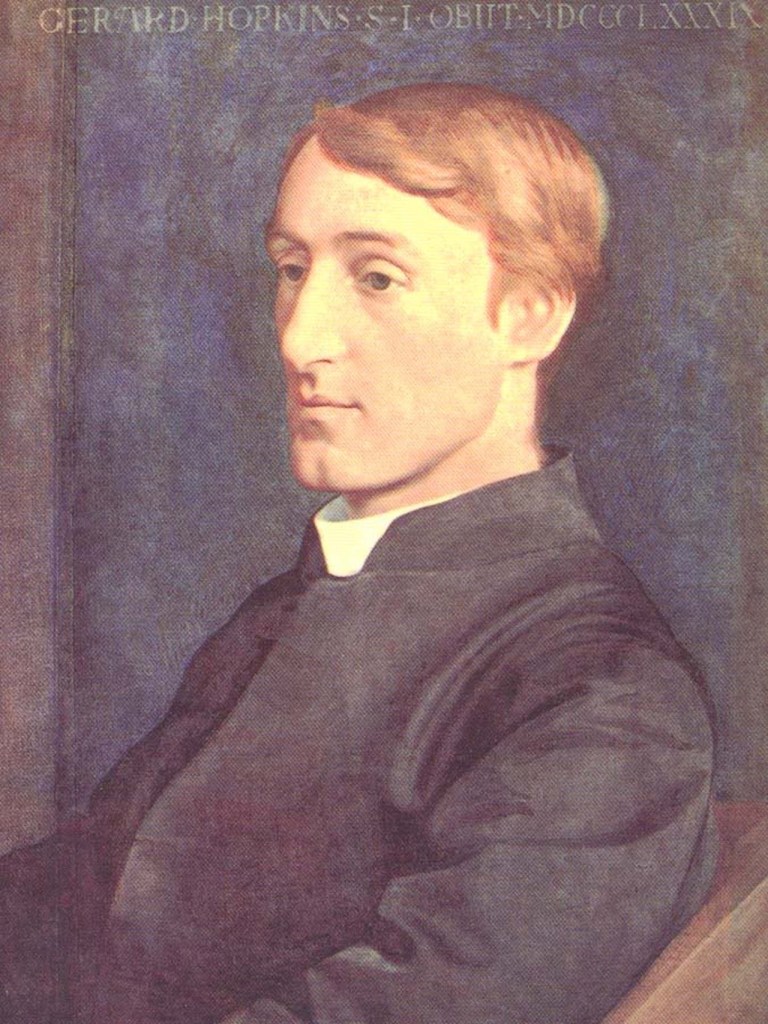

Image: Gerard Manley Hopkins

Religious Vocation: Joining the Jesuit Order

After graduating from Oxford with first-class honors in the Classics in 1867, Hopkins decided to pursue a religious vocation In 1868, he joined the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits), beginning his novitiate at Manresa House in Roehampton. As part of his training, he took vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

Hopkins believed that his religious commitment required him to renounce personal ambition, including his aspirations as a poet. In an act of self-denial characteristic of his Jesuit discipline [3], he burned many of his early poems upon entering the order. For several years, he refrained from writing any poetry at all.

During this pause from creative writing, Hopkins’s religious studies deepened his understanding of theology and philosophy. He studied at Stonyhurst College in Lancashire before moving to St. Beuno’s College in North Wales to study theology [6]. It was during this period that he began to reconcile his poetic gift with his spiritual calling.

The Wreck of the Deutschland: A Return to Poetry

In 1875, an event occurred that reignited Hopkins’ poetic creativity: the wreck of the German ship Deutschland off the coast of England. Among those who perished were five Franciscan nuns fleeing anti-Catholic persecution in Germany [1]. Deeply moved by their sacrifice and martyrdom, Hopkins composed The Wreck of the Deutschland, a long narrative poem that marked his return to writing.

The poem is notable for its novel experimentation with language and form. It introduced what Hopkins called “sprung rhythm,” a metrical system based on stressed syllables rather than traditional foot-based metrics. Sprung rhythm allowed him greater flexibility in capturing natural speech patterns while maintaining musicality.

Although The Wreck of the Deutschland was not published during Hopkins’s lifetime (it was deemed too unconventional), it signaled the beginning of his mature poetic phase. Over the next decade, he would compose some of his most celebrated and later anthologized works.

Major Themes and Innovations

Hopkins’s poetry is characterized by its vivid imagery, innovative use of language, and deep spiritual resonance. Central themes include the following:

Nature

Hopkins viewed nature as a manifestation of God’s glory—a concept he expressed through what he called “inscape,” or the unique essence of each created thing. Poems like “Pied Beauty” celebrate the variety and intricacy of nature:

“Glory be to God for dappled things—

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;”

Religion

As a devout Jesuit priest, Hopkins often explored themes of faith, grace, and divine presence. In “God’s Grandeur,” he reflects on humanity’s relationship with the Divine Reality (God): “The world is charged with the grandeur of God.”

Human Struggle

Hopkins did not shy away from depicting despair and inner turmoil. His so-called “terrible sonnets,” written during periods of depression in Dublin later in life (“No Worst There Is None” and “I Wake And Feel The Fell Of Dark”), are raw expressions of spiritual desolation.

Language

Hopkins’s creative inventiveness set him apart from other Victorian poets. He employed compound words (“dapple-dawn-drawn”), alliteration (“kingdom of daylight’s dauphin”), and unconventional syntax to create striking effects. It might be noted that E. E. Cummings’ innovation remains a 20th century parallel to that of Father Hopkins 19th century foray into stylizing novelty.

Academic Career in Dublin

In 1884, after years serving as a parish priest in England and Scotland (often under challenging conditions), Hopkins was appointed Professor of Greek Literature at University College Dublin.

While teaching brought him some satisfaction intellectually, he still continued to struggled with feelings of isolation as an Englishman residing and working in Ireland during a time of political upheaval.

Image: Gerard Manley Hopkins

Death and Legacy

Father Hopkins’ final years were marked by declining health and bouts of depression—what he referred to as “the long dark night.” Despite these challenges, he continued writing poetry until shortly before his death.

Father Hopkins died on June 8, 1889, at the age of 44 from typhoid fever in Dublin. At the time of his death, none of his major poems had been published; they existed only in manuscript form.

It was not until 1918—nearly three decades after his death—that Robert Bridges edited and published the collection simply titled Poems, bringing Hopkins’ work to public attention for the first time. The collection received mixed reviews initially but gained increasing recognition over time.

By the mid-20th century, critics such as F.R. Leavis had established Hopkins as one of the most original voices in English poetry. His innovative techniques anticipated modernist trends seen later in poets like T.S. Eliot, Dylan Thomas, and E. E. Cummings.

Father Gerard Manley Hopkins remains one of English literature’s most enigmatic figures—a poet-priest whose work brought together certain Victorian sensibilities with modernist experimentation. His legacy rests not only in his technical innovations but also in his ability to convey profound spiritual truths through language that continues to resonate with readers today.

Sources

[1] Gerard Manley Hopkins. Poems. Edited by Robert Bridges. Oxford University Press. 1918.

[2] Gerard Manley Hopkins. Poems and Prose. Edited by W. H. Gardner. Penguin Classics. 1953.

[3] Eleanor Ruggles. Gerard Manley Hopkins: A Life. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. 1944.

[4] Norman H. Mackenzie. A Reader’s Guide to Gerard Manley Hopkins. Cornell U P. 1981.

[5] John Cowie Reid. “Gerard Manley Hopkins.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. Accessed January 1, 2026.

[6] Curators. “Gerard Manley Hopkins.” Poetry Foundation. Accessed January 1, 2026.

🕉

You are welcome to join me on the following social media:

TruthSocial, Locals, Gettr, X, Bluesky, Facebook, Pinterest

🕉

Share

Poem Commentaries

- Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “God’s Grandeur” Father Gerard Manley Hopkins’ motivation to imitate Spirit (God) prompts him to craft his poems in forms, as Spirit creates entities in forms—from rocks to animals to plants to the human body.

- Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “Pied Beauty.” Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “Pied Beauty” is an eleven-line curtal sonnet dedicated to honoring and praising God for the special beauty of His creation. Father Hopkins coined the term “curtal” to label his eleven-line sonnets.

- Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “The Habit of Perfection” The title “The Habit of Perfection” of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem features a pun on the term “habit.” As a monk, the poet had accepted the garb of the monastic, sometimes called a habit.