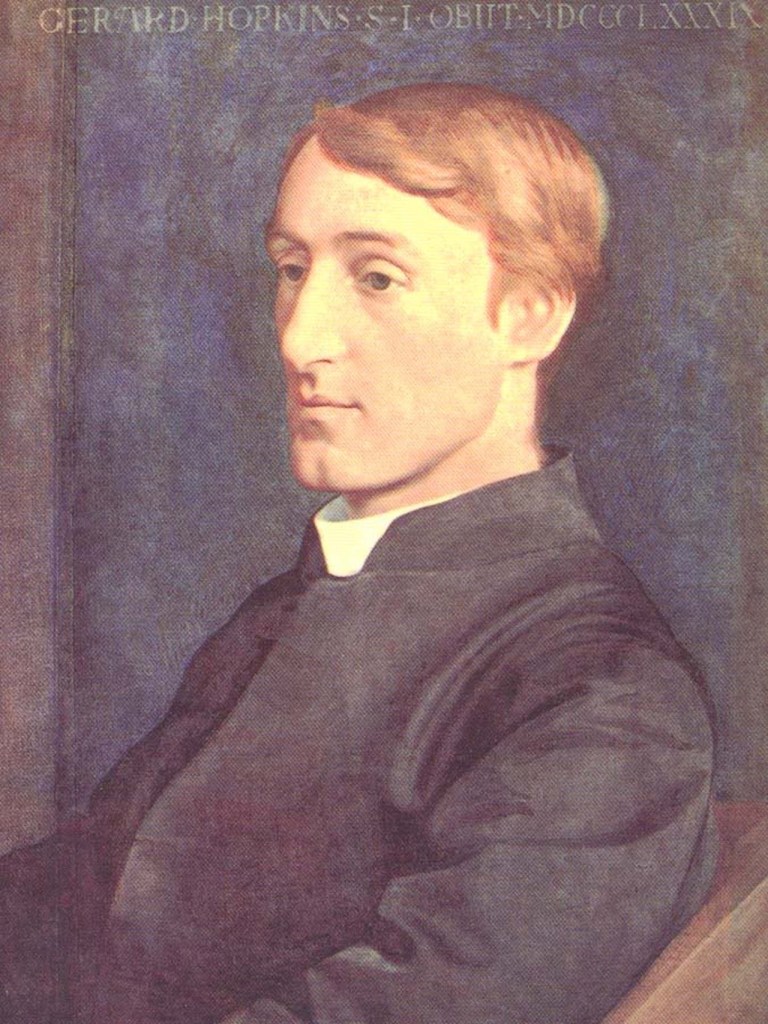

Image: Gerard Manley Hopkins

Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “God’s Grandeur”

Despite the “smudge” and “smear” from some human activity, the speaker is offering assurance that the Creator’s blessings and restoration of Planet Earth remain in effect through the “grandeur” of that Creative Force-God. Instead of instilling fear of earthly events, he encourages worship.

Introduction with Text of “God’s Grandeur”

Father Gerard Manley Hopkins’ motivation to imitate Spirit (God) prompts him to craft his poems in forms, as Spirit creates entities in forms—from rocks to animals to plants to the human body.

Father Hopkins often employs the sonnet form. “God’s Grandeur” is a sonnet—fourteen lines, more similar to the Petrarchan than the Elizabethan. The first eight lines (octave) present an issue; then, the remaining six lines (sestet) address that issue.

Father Hopkins’ rime scheme is typically ABBAABBA CDCDCD, which also resembles the Petrarchan rime scheme in the octave. He employs iambic pentameter but varies from spondee to trochee. Father Hopkins’ called his unique form “sprung rhythm.”

God’s Grandeur

The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man’s smudge and shares man’s smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And though the last lights off the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs —

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

Reading:

Commentary on “God’s Grandeur”

Decrying the “smudge” and “smear” from human activity, the speaker asserts that despite humankind’s penchant for defiling nature, the Creator continues to bless and restore the world—a message that flies in the face of climate alarmists.

However, in today’s smudged, postmodern world, one pays a price for criticizing climate alarmists who have replaced faith in the Creator with constant agitation for political ascendency.

The Octave: Pantheistic View of God

The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man’s smudge and shares man’s smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

The speaker in this Petrarchan sonnet sees God everywhere: “The world is charged with the grandeur of God.” His soul is convinced, but his senses tell him that people do not behave as if this were true: “Why do men then not reck his rod?”

Not only do men, i.e. humankind, not heed the Divine, they also seem content to exist in darkness from where they spread gloom on the environment. The speaker contends that whole generations of humanity have trampled the earth, defiling nature as they apply their systems of “trade.”

The speaker is dramatizing Father Hopkins’ sense that human beings have become more interested in materialistic gain and possessions than in celebrating the glory of a loving, merciful, Heavenly Father.

The Sestet: God’s Gifts Cannot Be Exhausted

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And though the last lights off the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs —

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

The octave has presented the issue: humankind is oblivious to God’s gifts and thus defiles them. The sestet addresses the issue: despite indifference to the Creator, humankind cannot exhaust the gifts that the Creator bestows, because nature continues to renew itself through the agency of the Divine.

Thus, a “dearest freshness” continues to assert itself, despite the dirty ways of humankind. Humankind may disregard God’s grandeur, but everything renews despite human activity.

The speaker’s faith leaves him no room for doubt, because that faith has infused in him the intuition that the “Holy Ghost” is always watching over humankind, the children of Spirit-God, somewhat like a mother bird watches over her little flock.

The Holy Ghost (Divine Mother) will ever mother humanity—Her little birds. Father Hopkins’ mystical insight brings him to the faith that throbs in his soul—in his “inscape,” his unique term for his inner landscape.

The Mystical Poet and God’s Creation

And “in the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (KJV, John 1:1). This line speaks gently but firmly to the inner ear of mystically inclined poets.

As originally determined, a poet is a word craftsman, and when the poet of genuine faith builds with words, he is imitating God, taking his discourse out of dogma and into true spirituality. The form of “God’s Grandeur” closely resembles Father Hopkins’ other poems.

In “The Windhover,” the rime scheme is the same as that of “God’s Grandeur.” The same is true for “The Lantern out of Doors,” “Hurrahing in Harvest,” and “As Kingfishers Catch Fire.”

Father Hopkins sonnets celebrate Spirit and continue the search for a deeper relationship with the Mastercraftsman (God). Occasionally, as he structures his sonnets, they produce an order that further marks a style uniquely his own.

Readers do not encounter any structure resembling “Stirred for a birds, the achieve of, the mastery of the thing” in a Thomas Hardy or A. E. Housman poem—or that of any other poet—the uniqueness of Father Hopkins is so firmly established.

Also, a typical line of Father Hopkins is “Let him easter in us, be a dayspring to the dimness of us, be a crimson-cresseted east,” which contains the example of his meter and content.

Divine Melancholy

The melancholy experienced by Father Gerard Manley Hopkins is of divine origin. The ameliorist in Thomas Hardy produces in his poems a different sort of melancholy. Father Hopkins has faith; Hardy has hope. One may deem Hardy spiritually adrift on the sea of humankind’s woe, even when he sings,

I talk as if the things were born

With sense to work its mind;

Yet it is but one mask of many worn

By the Great Face behind.

Referring to the veiled nature of God, Hardy seems to bemoan it rather than celebrate it, as Father Hopkins does. Housman is preoccupied with endings. He says, “And since to look at things in bloom / Fifty springs are little room” and “sharp the link of life will snap.”

Of course, all poets are concerned with endings, but each poet in his work will treat those concerns in distinctive ways, according to their levels of understanding and faith. Hardy, Housman, and many other poets remain earthbound looking for answers to ultimate questions among the various outlets for human intellectual expression. And their search is a vital one for humankind.

However, Father Hopkins’ “God’s Grandeur” along with the rest of his canon affords the reader the experience of hearing beautiful singing loud and sweet a poet’s song of the love for the Divine.

Father Hopkins’ faith set him free to pursue and express Divine Love, instead of endless searching for that something-else that the faithless heart craves as it laments the trammels of Earth.

🕉

You are welcome to join me on the following social media:

TruthSocial, Locals, Gettr, X, Bluesky, Facebook, Pinterest

🕉

Share