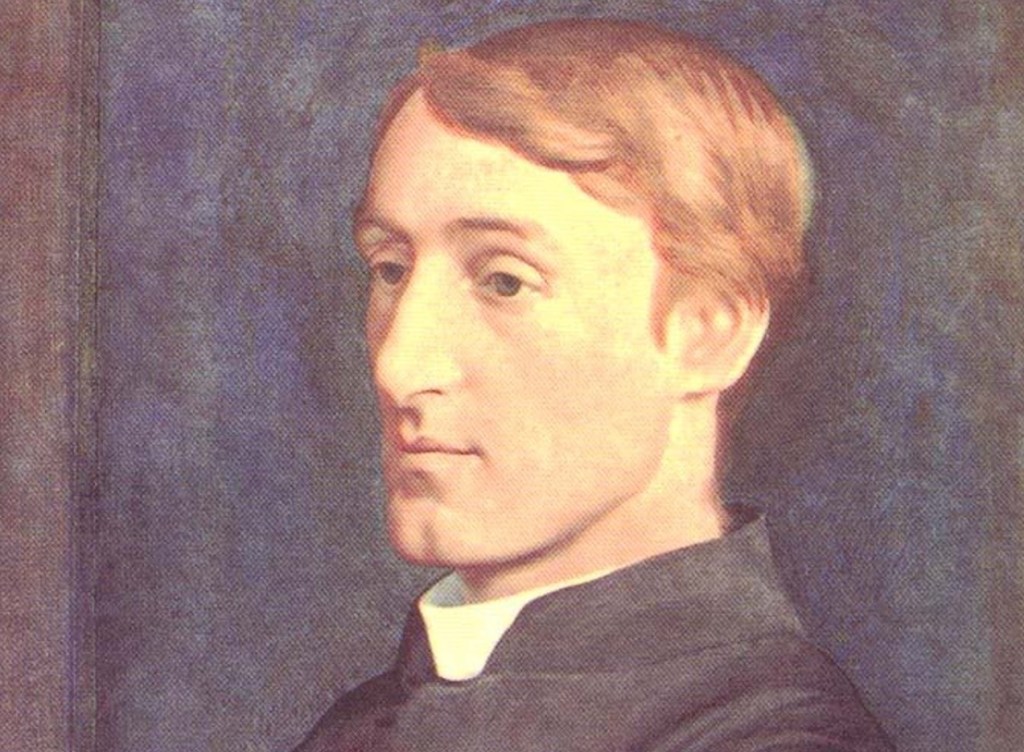

Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day”

The speaker Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day” is confronting spiritual desolation, interior darkness, and the sense of abandonment by God.

Awakening into psychological night, the speaker measures time not in hours but in years of suffering. His cries feel unheard, like letters sent to one who lives far away. In the sestet, suffering turns inward as his soul becomes both the source and the punishment of torment.

Introduction and Text of “I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day”

This sonnet is the second installment belonging to the group of six poems often called the “terrible sonnets.” They focus on intense inward struggle in highly compressed language, and they reveal a profound sense of spiritual trial. The speaker is describing an internal condition of darkness that persists even after waking.

The poem follows the traditional Petrarchan structure, but the poet displayed the poem on the page separating the octave into two quatrains and the sestet into two tercets. The octave presents the condition of suffering, followed by the sestet which deepens and internalizes that suffering. The language remains quite visceral, yet sacramental and judicial, suggesting punishment and endurance.

I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day

I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day.

What hours, O what black hours we have spent

This night! what sights you, heart, saw; ways you went!

And more must, in yet longer light’s delay.

With witness I speak this. But where I say

Hours I mean years, mean life. And my lament

Is cries countless, cries like dead letters sent

To dearest him that lives alas! away.

I am gall, I am heartburn. God’s most deep decree

Bitter would have me taste: my taste was me;

Bones built in me, flesh filled, blood brimmed the curse.

Selfyeast of spirit a dull dough sours. I see

The lost are like this, and their scourge to be

As I am mine, their sweating selves, but worse.

Reading

Commentary on “I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day”

In the octave, the speaker presents spiritual suffering as prolonged night and unanswered prayer, while the sestet reveals suffering as internalized judgment.

Octave: “I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day.”

I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day.

What hours, O what black hours we have spent

This night! what sights you, heart, saw; ways you went!

And more must, in yet longer light’s delay.

With witness I speak this. But where I say

Hours I mean years, mean life. And my lament

Is cries countless, cries like dead letters sent

To dearest him that lives alas! away.

The octave opens abruptly: “I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day.” The speaker awakens, yet awakening does not bring light. The word fell suggests something savage, cruel, or deadly, as though darkness itself were an attacking force.

Day has failed to arrive, not externally but internally. The speaker’s consciousness remains trapped in night. This darkness is not merely the absence of light but a palpable weight that can be felt.

The second line intensifies this experience. The repetition emphasizes exhaustion. These hours are not ordinary; they are “black hours,” heavy with dread. The speaker addresses his own heart directly, asking it to remember what it has seen and where it has wandered, suggesting a night filled with disturbing thoughts, memories, or spiritual visions that cannot be escaped even in sleep.

The line “And more must, in yet longer light’s delay” extends the suffering into the future. Relief is postponed; light is delayed. The speaker anticipates further endurance without comfort. The octave has thus established a defining theme: suffering continues; the speaker is conscious of the fact that it is also unavoidable.

In the second quatrain, the speaker asserts his testimony. He is not exaggerating or indulging emotion; instead, he is claiming authority as one who has endured. Yet immediately, time expands. When he says “hours,” he means “years,” and beyond that, “life.” What began as a single night becomes a metaphor for an entire existence marked by anguish. The darkness is not episodic but continually defining.

The lament itself takes the form of “cries countless.” These cries are compared to missives sent to a loved one far away. The metaphor is striking. The speaker believes his cries are addressed to God, “dearest him,” yet they receive no reply. Like letters that never reach their destination, these prayers feel wasted, unheard, and perhaps unopened. God is known to be living, yet distant.

The emotional force of the octave lies in this tension: the speaker continues to cry out, continues to bear witness, even while believing those cries go unanswered. The speaker is not revealing disbelief but instead he is demonstrating faith that yet suffers.

The speaker holds no compunction to deny God’s existence, a suffering humanity often is wont to do; instead, he suffers under God’s silence. The speaker therefore is expressing despair not as rebellion but as endurance under abandonment. The night continues, the cries continue, and the speaker remains awake within it.

Sestet: “I am gall, I am heartburn. God’s most deep decree”

I am gall, I am heartburn. God’s most deep decree

Bitter would have me taste: my taste was me;

Bones built in me, flesh filled, blood brimmed the curse.

Selfyeast of spirit a dull dough sours. I see

The lost are like this, and their scourge to be

As I am mine, their sweating selves, but worse.

The sestet takes a decisive inward turn. Where the octave emphasized time and unanswered cries, the sestet focuses on the body and self as the site of punishment. The speaker does not merely feel bitterness; he is bitterness. Gall, a bitter substance associated with suffering and poison, suggests spiritual nausea. Heartburn implies a burning from within, a pain generated internally rather than inflicted from without.

The speaker attributes this condition to “God’s most deep decree.” This suffering is not accidental or random. It is permitted, even ordained. The bitterness is something the speaker must taste, yet the shocking revelation follows: “my taste was me.” The self (soul) becomes both the instrument and the substance of suffering. There is no external punishment necessary; identity itself is the affliction.

The line “Bones built in me, flesh filled, blood brimmed the curse” intensifies the embodiment of despair. The curse is not simply symbolic; it saturates the physical body. Bones, flesh, and blood—the fundamental elements of life—are all implicated. Suffering is total, leaving no refuge within the soul. The speaker’s claims suggest a complete inhabitation or incarnation of pain, as though despair has become structural.

The metaphor of fermentation is created in the line “Selfyeast of spirit a dull dough sours.” Yeast is normally a source of growth and life, but here it produces sourness. The spirit works upon itself destructively. The self generates its own decay. This image reinforces the idea that suffering is self-contained, inescapable, but continuous.

In the final lines, the speaker broadens his vision. He recognizes his condition as a foretaste of damnation. The lost are punished not by external flames but by being trapped within themselves. Their scourge is to be “their sweating selves.” The speaker identifies with this fate, acknowledging that he already experiences something like it, though he believes theirs will be worse.

The sestet ends without consolation. There is no resolution, no light breaking through. Instead, the poem concludes with recognition and endurance. The speaker understands the nature of suffering more clearly, but understanding does not remove it. The sonnet closes in grim clarity rather than hope.

🕉

You are welcome to join me on the following social media:

TruthSocial, Locals, Gettr, X, Bluesky, Facebook, Pinterest

🕉

Share