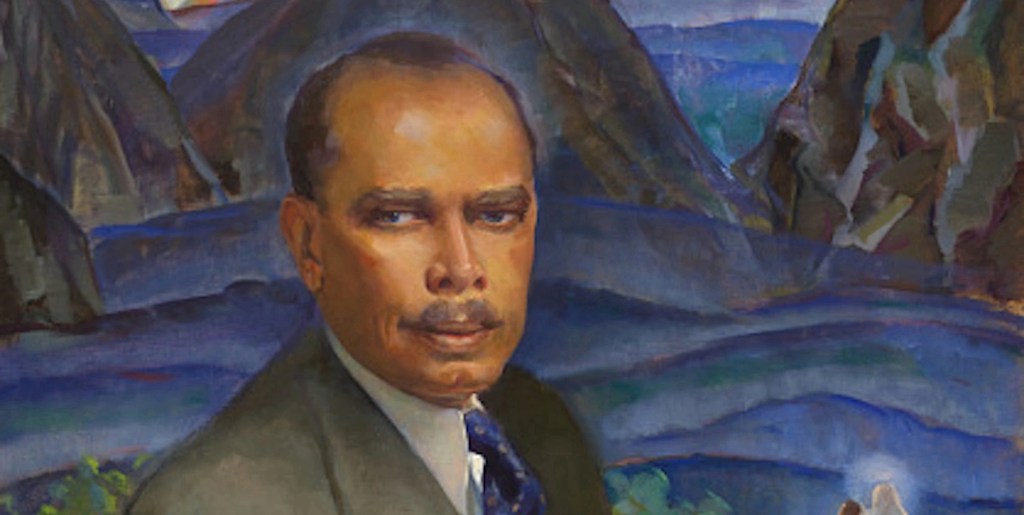

Image:James Weldon Johnson – Portrait by Laura Wheeler Waring

Life Sketch of James Weldon Johnson

A true “Renaissance man,” James Weldon Johnson wrote some the best spiritual poems and songs in the American literary canon. He also held positions as attorney, diplomat, professor, and activist in a political party, fighting for the civil rights of black Americans.

(Note on Term Usage: Before the late 1980s, the terms “Negro,” “colored,” and “black” were accepted widely in American English parlance. Then in 1988, the Reverend Jesse Jackson began insisting that Americans adopt the phrase, “African American.” The earlier more accurate terms were the custom at the time James Weldon Johnson was writing.)

Early Life and Schooling

James Weldon Johnson was born on June 17, 1871, in Jacksonville, Florida, [1] to James Johnson, of Virginia, who had held a position as headwaiter at a resort hotel, and Helen Louise Dillet, of the Bahamas, who had served as a teacher in Florida.

His parents raised James to be a strong, independent man. The future poet became a free-thinker as his parents encouraged him to understand that he was capable of achieving all the success in life for which he sought to strive.

In 1894, after completing the bachelor’s degree at Atlanta University, he accepted a position as principal at the Edwin M. Stanton School. His mother had taught at that school. In his position as principal of Stanton, he made great improvements in the curriculum, adding grades 9 and 10.

While serving at the Stanton school as principal, Johnson founded the newspaper, The Daily American. The paper remained in publication for only a year, but it served as a lever for Johnson’s role as an activist, bringing him to the attention of Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois, two of the most influential activists of the civil rights movement.

Johnson began the study of law in Thomas Ledwith’s law office in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1896 [2]. He passed the bar exam in 1898 and was admitted to the Florida bar. He practiced law for several years and then decided to pursue other lines of work.

From New York City to the Diplomatic Corp

To engage a career in songwriting, in 1901 James and his brother Rosamond moved to New York City. They became partners with Bob Cole and accepted a publishing contract which paid a $1200 monthly stipend. That income amounted to a fortune in the early 20th century.

During the next half decade, the Johnson brothers wrote and produced a whopping 200 songs for both Broadway and for other formats. Their substantial list of hits include titles such as “Didn’t He Ramble,” “Under the Bamboo Tree,” and “The Old Flag Never Touched the Ground.”

Along with Bob Cole, the Johnsons earned a outstanding reputation as a musical trio. They became known affectionately as “Those Ebony Offenbachs.” While they eschewed the artistry of the minstrel show stereotypes, they did agree to create simplified versions of black life of rustics for white audiences that seemed to relish such fare.

But their most important contribution includes a suite of six songs titled The Evolution of Ragtime, a documentary which has remained important for recording the black experience in contributing to music. Residing in New York also allowed Johnson the opportunity to attend Columbia University, where he engaged formally in the study literature and creative writing.

Johnson also began his civil rights activism in Republican Party politics. While serving as the treasurer of New York’s Colored Republican Club, he wrote two songs for Theodore Roosevelt’s 1904 presidential campaign. Roosevelt won that campaign, becoming the 26h president of the United States.

The black national civil rights leadership divided into two factions: one remained traditional and was led by Booker T. Washington. The other faction turned radical and was headed up by W.E.B. Du Bois. Johnson chose to follow Washington and the traditionalists.

Washington’s leadership had offered the appropriate influence and had helped Roosevelt win the presidency. Thus, Washington exerted his influence again to have Johnson appointed as the U.S. consulate to Venezuela.

Johnson’s stint in Venezuela afforded him time to create poetry. There he composed his magnificent, nearly perfect sonnet, “Mother Night,” during this time. Also, during this three year period of service as consul on Venezuela, he was able to finish his novel, The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man.

After Johnson’s service in Venezuela, he received a promotion that relocated him to Nicaragua. His job in Nicaragua became more demanding, allowing him less time for literary efforts.

Back to New York and the Harlem Renaissance

In 1900, Johnson composed the hymn “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” for a school celebration of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday [3]. His brother Rosamond later added the melody to the lyric. In 1919, the National Association for Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) designated the song the “Negro National Hymn (Anthem).”

In 1913, because of the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat, Johnson resigned his foreign service position and returned to the U.S.A. In New York, Johnson began writing for New York’s prestigious black newspaper, the New York Age. He wrote essays explaining and promoting the importance of the hard-work ethic and education.

Johnson’s traditionalism kept his position more in line with Booker T. Washington than with the radical militant W.E.B. Du Bois. Despite those differences in ideologies, Johnson remained on good terms with both activists.

In 1916, after Du Bois suggested the position to Johnson, he accepted the role as secretary in the NAACP. In 1920, Johnson led the organization as president. Despite his many activist duties with the NAACP, Johnson dedicated himself to writing full time. In 1917, he published his first collection of poems, Fifty Years and Other Poems. That collection received great critical acclaim and established him as an important voice in the Harem Renaissance Movement.

Johnson continued writing and publishing; he also served as editor for numerous volumes of poetry, such as The Book of American Negro Poetry (1922), The Book of American Negro Spirituals (1925), and The Second Book of Negro Spirituals(1926).

In 1927, Johnson published his second book of poems God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse [4]. Again, his collection received much praise from critics. Dorothy Canfield Fisher, a best-selling author and activist for education reform, stated in a letter about Johnson’s style:

. . . heart-shakingly beautiful and original, with the peculiar piercing tenderness and intimacy which seems to me special gifts of the Negro. It is a profound satisfaction to find those special qualities so exquisitely expressed.

Back to Teaching

After his retirement from the NAACP, Johnson continued writing. He also served as professor at New York University. Johnson’s stellar reputation again preceded him; as he joined the NYU faculty, Deborah Shapiro testified:

Dr. James Weldon Johnson was already a world-renowned poet, novelist, and educator when he arrived at the School of Education in 1934. His faculty appointment was in the Department of Educational Sociology, yet Johnson’s influence did not end there. As the first black professor at NYU, Johnson broke a crucial color barrier, inspiring further efforts toward racial equality both within and outside the boundaries of Washington Square.

Death

In 1938 at age 67, Johnson was killed in an automobile accident in Wiscasset, Maine, after a train crashed into the vehicle in which the poet was a passenger. His funeral, held in Harlem, New York, was attended by over 2000 individuals.

Johnson’s creative power and activism rendered him a true “Renaissance man,” who lived a full life. He penned some of the finest poetry and songs ever to appear on the American literary and music scenes. Johnson’s life creed bestows on the world an uplifting inspiration after which any individual might choose to chisel his life:

I will not allow one prejudiced person or one million or one hundred million to blight my life. I will not let prejudice or any of its attendant humiliations and injustices bear me down to spiritual defeat. My inner life is mine, and I shall defend and maintain its integrity against all the powers of hell. [5]

The poet’s body is interred in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York [6]. In an unconventional final expression, his body has been arrayed in his favorite lounging cape, with his hands clutching a copy of his collection God’s Trombones.

Sources

[1] Editors. “James Weldon Johnson.” Famous African Americans. Accessed January 27, 2023.

[2] Malik Simba. “Profile: James Weldon Johnson (1871- 1938).” Black Art Story. Accessed January 27, 2023.

[3] Editors. “The Story Behind the Black National Anthem.” Black Excellence. September 26, 2018.

[4] Editors. “James Weldon Johnson.” Poetry Foundation. Accessed January 27, 2023.

[5] Christine Weerts. “How ‘Lift Every Voice And Sing’ Became A Song Of Hope For Generations.” The Federalist. February 12, 2021.

[6] FindAGrave. “James Weldon Johnson.” Accessed January 27, 2023.

Commentaries on Poems by James Weldon Johnson

This room in my literary home holds links to poems written by James Weldon Johnson along with commentaries on the poems.

Poems with Commentaries

- “Noah Built the Ark”

- “Go Down Death”

- “Sence You Went Away”

- “Fifty Years”

- “A Poet to His Baby Son”

- “Lift Every Voice and Sing”

- “Mother Night”

- “The Creation”

- “O Black and Unknown Bards”

- “My City”

🕉

You are welcome to join me on the following social media:

TruthSocial, Locals, Gettr, X, Bluesky, Facebook, Pinterest

🕉

Share

Full Image:James Weldon Johnson – Portrait by Laura Wheeler Waring