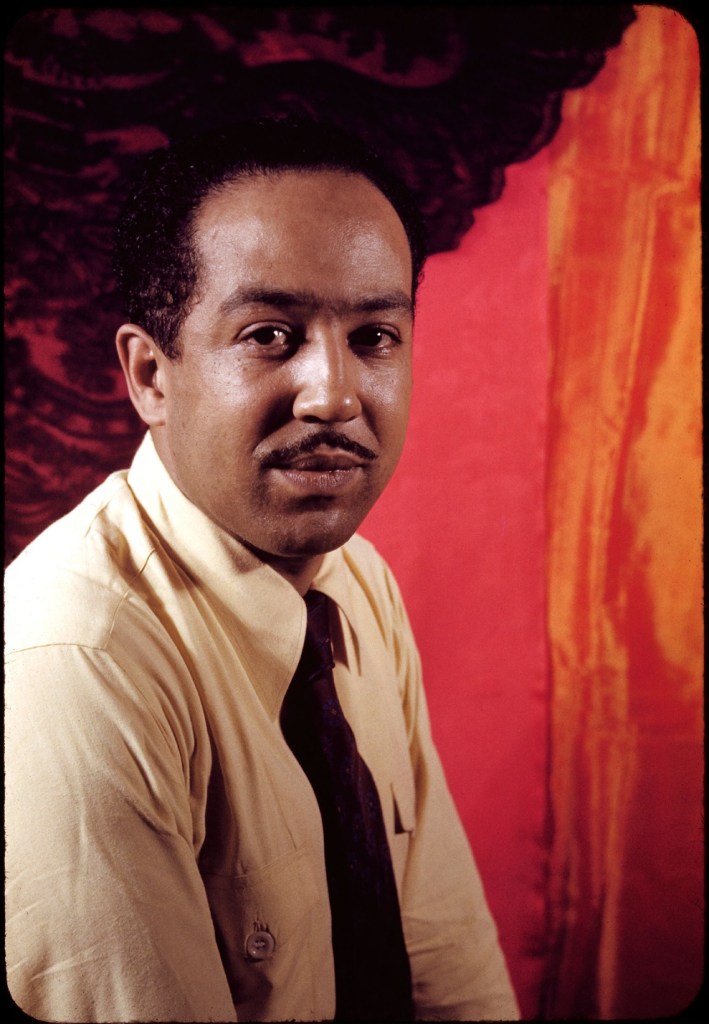

Image: Langston Hughes Carl Van Vechten Trust / Beinecke Library, Yale

Life Sketch of Langston Hughes

Hoyt W. Fuller, critic, editor, and founder of the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC), has pointed out that Langston Hughes possessed a “deceptive and profound simplicity.” Fuller insists that understanding these qualities in Hughes is key to understanding and appreciating his poetry.

Early Life and Education

On February 1, 1902, Langston Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri, to James Nathaniel Hughes and Caroline Mercer Langston. The poet’s full name is James Mercer Langston Hughes. His parents divorced when Langston was very young, and he was raised primarily by his grandmother in Lawrence, Kansas [1]. In his first autobiography, The Big Sea, Hughes reveals,

My grandmother raised me until I was twelve years old. Sometimes I was with my mother, but not often. My mother and father had separated. And my mother, who worked, always traveled about a great deal, looking for a better job.

When I first started to school, I was with my mother a while in Topeka. (And later, for a summer in Colorado, and another in Kansas City.) She was a stenographer for a colored lawyer in Topeka, named Mr. Guy. She rented a room near his office, downtown. So I went to a “white” school in the downtown district.[2]

The poet’s father James Hughes had studied law and had planned to practice, but Jim Crow laws prevented him from taking the bar exam. The elder Hughes then moved to Mexico, where not only was he admitted to the bar, but he also became very successful through the practice of law.

Langstons’ father’s financial success allowed him to become the owner of much property in Mexico City, where nearby he purchased and resided on a huge ranch in the hills. He also became a money lender and foreclosed on mortgages.

About his father, the poet has remarked, “my father was interested in making money to keep.” This attitude contrasted with his mother and his stepfather, who were interested in making money to spend. Thus, his mother and stepfather moved around a great deal to take advantage of better employment.

In 1920, Langston Hughes graduated from Central High School in Cleveland, Ohio. He had hopes of attending Columbia University to study to become a writer, but his father refused to pay for his son’s schooling unless the younger Hughes studied engineering.

Hughes started his university studies at Columbia but stayed for only a year. He found racism at the school intolerable, so he left the university and took a number of jobs to support himself.

In 1929, Hughes completed his university studies at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. The school pays tribute to their most famous graduate with a library named in his honor, Langston Hughes Memorial Library [3].

Full Image: Langston Hughes Carl Van Vechten Trust / Beinecke Library, Yale

Poetry

Langston Hughes opens his first autobiography, The Big Sea, by reporting on a melodramatic event: he is tossing into the ocean one by one all the books he had studied while at Columbia University.

He had recently joined the large merchant ship S. S. Malone as a seaman; he was only twenty-one years old, and he made up his mind that nothing would ever again happen to him that he did not want to have happen.

He became intent on securing his own freedom with his little dramatic ritual of unloading his college books into the ocean. In the life of Langston Hughes, one poetic act often led to another. Four years before this important, liberating act, however, the poet had traveled to Mexico to visit his father to ask for financial assistance to attend the university.

But he reports that his visits with his father in Mexico were mostly unsatisfactory; he could not identify with his father’s mindset. His father hated his own race of people, and he was interested only in making money. However, Langston needed his father’s financial support, so he spent time with him in Mexico.

On this particular trip, while Hughes was only seventeen years old, the poet composed one of his most anthologized poems “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.” He gives details of his inspiration for this poem in The Big Sea; he wrote the poem “just outside of St. Louis, as the train rolled toward Texas”:

It came about in this way. All day on the train I had been thinking about my father and his strong dislike of his own people. I didn’t understand it, because I was a Negro, and I liked Negroes very much.

He then describes meeting a number of blacks who had come “up from the South” as he worked at one of his “happiest jobs” at a soda fountain. He reports that he enjoyed “hearing them talk, listening to the thunderclaps of their laughter, to their trouble, to their discussions of the war and the men who had gone to Europe from the Jim Crow South, their complaints over the high rent. . . .” To Hughes, these people seemed to be the “gayest and bravest people possible” as they worked “trying to get somewhere in the world.”

Crossing the Mississippi River at sunset, Hughes peered out of the Pullman window and saw “the great muddy river flowing down toward the heart of the South,” and he started musing on “what the river, the old Mississippi, has meant to Negroes in the past.”

He mused on the tragedy of slaves being sold down the river as the “worst fate” that a slave could suffer. He then began musing on President Abraham Lincoln’s having rafted on the Mississippi down to New Orleans. Lincoln had seen “slavery at it worst, and had decided within himself that it should be removed from American life.”

Hughes’ musing in this creative reverie then turned to additional rivers that had affected the lives of members of his ethnicity: the Congo, the Niger, and the Nile. And then the thought came to him: “I’ve known rivers.”

He wrote down that one line on an envelope holding the letter from his father which he carried in his pocket, and then within the next fifteen minutes, he had composed his magnificent poem, which he titled “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.”

As one of the most important creative contributors to the Harlem Renaissance, Hughes has offered many poems to the American literary canon. A small sample of his poems include “A Mother to Son,” “Madame’s Calling Cards,” “Theme for English B,” “Night Funeral in Harlem,” “Goodbye, Christ,” and “Cross.”

Supporting Himself by Writing

Langston Hughes has been most noted as a poet, and he managed to finish his college education after being awarded a full scholarship based on his proficiency as a poet. After receiving his B.A. degree in 1929, he continued to publish widely, earning for himself the achievement of being a writer, who was able to support himself as an adult solely with his writings [4].

In addition to poetry, which remained his first love, Hughes published three novels, Not without Laughter (1932), Scottsboro Limited (1932), and The Ways of White Folks (1934). In 1935, Hughes was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship. The Gilpin Players (Karamu House) produced six of the poet’s plays in 1936 and 1937. Hughes founded the Negro Theater in Los Angeles in 1939 and composed the script “Way Down South.”

Hughes published eight collections of poems; he also published four books of fiction and six books for children and teens. He added three books of humor to his resume as well as two autobiographies. He also wrote essays and a number of books on black history. As a prominent figure in the civil rights movement, he traveled and lectured widely throughout the world [5].

Illness and Death

In 1967, at the Stuyvesant Polyclinic in New York City, Hughes submitted to t0 a surgical procedure to treat prostate cancer. The surgery was a tragic failure, and he died from complications arising from that medical procedure [6]. Hughes’ body underwent cremation, and his ashes remain interred at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, under the floor of the foyer in the institute.

The artwork on the flooring features a medallion of a human being formed by rivers and includes the line, “My soul has grown deep like the rivers,” from the poet’s inspirational poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.”

Sources

[1] Editors. “Langston Hughes: 1902–1967.” Poetry Foundation. Accessed January 12, 2026.

[2] Langston Hughes. The Big Sea: An Autobiography. Thunder’s Mouth Press. New York. 1940. 1986. Print.

[3] Editors. “About the Library.” Lincoln University. Accessed January 12, 2026.

[4] Langston Hughes. I Wonder as I Wander: An Autobiographical Journey. Thunder’s Mouth Press. New York. 1956. 1986. Print.

[5] Curators. The Langston Hughes Society. Horsham, Pennsylvania. Accessed January 12, 2026.

[6] Editors. “Langston Hughes.” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History: Case Western Reserve University. Accessed January 12, 2026.

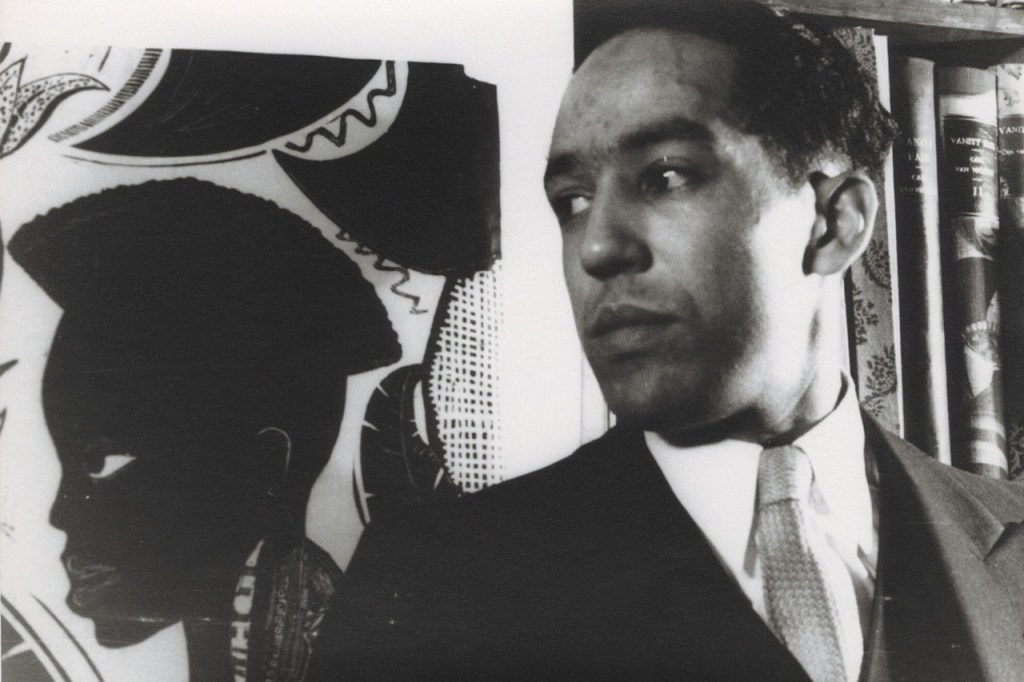

Image: Langston Hughes – Poetry Foundation

Commentaries on Langston Hughes Poems (forthcoming)

- “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” Langston Hughes’ speaker in “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” displays his message with a “cosmic voice,” which includes and unites all of humanity. The poem plays out in five versagraphic movements, focusing on the theme of soul exploration.

- “Harlem” Langston Hughes became the most influential poet of the Harlem Renaissance. His works focus primarily on the lives of the everyday working man or woman. He wanted to bring attention to those hard-working folks whose lives were under-appreciated.

- “A Mother to Son” The speaker in Langston Hughes’ narrative poem “Mother to Son” is engaging the literary device known as the dramatic monologue, a poetic device employed with expertise by the English poet, Robert Browning. In Langton Hughes’ narrative, a ghetto mother is advising her son about his direction in life.

- “Cross” The speaker in Langston Hughes’ “Cross” laments having been born to biracial parents, a white father and a black mother. But the poem merely dramatizes stereotypes, and that reliance limits its achievement. This poem fails to exemplify the true achievement of this poet.

- “Madam’s Calling Card” Alberta K. Johnson is a character in Langston Hughes’ twelve-poem set called “Madam to You.” In this poem, she has herself some name cards printed.

- “Night Funeral in Harlem” The speaker in Langston Hughes’ “Night Funeral in Harlem” wonders how this poor dead boy’s friends and relatives are able to afford such a lavish funeral. But he finally admits that the tears shed by the mourners are the feature that made the deceased’s funeral “grand.”

- “Theme for English B” The speaker is a non-traditional, older student in a college English class who has been given the assignment to write a paper that “come[s] out of you.” The instructor has insisted that the paper will be “true” if the student simply writes from his own heart, mind, and experience, but the speaker remains a bit skeptical of that claim, thinking that maybe he is unsure that it is “that simple.”

- “Goodbye, Christ” Langston Hughes wrote “Goodbye, Christ” in 1931. It was published in the statist publication called “The Negro Worker” in 1932, but Hughes later withdrew it from publication.

Note on Term Usage

Before the late 1980s in the United States, the terms “Negro,” “colored,” and “black” were accepted widely in American English parlance. While the term “Negro” had started to lose it popularity in the 1960s, it wasn’t until 1988 that the Reverend Jesse Jackson began insisting that Americans adopt the phrase “African American.” The earlier more accurate terms were the custom at the time that Langston Hughes was writing.

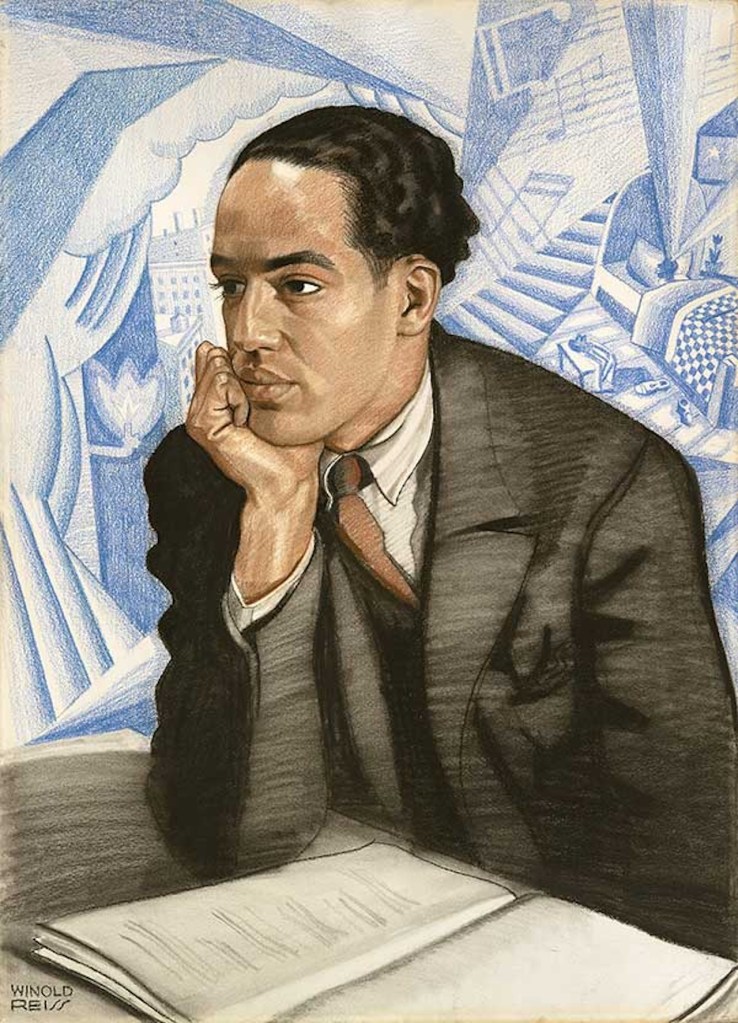

Image: Langston Hughes. Portrait by Winold Reiss (1886–1953) – National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

🕉

You are welcome to join me on the following social media:

TruthSocial, Locals, Gettr, X, Bluesky, Facebook, Pinterest

🕉

Share