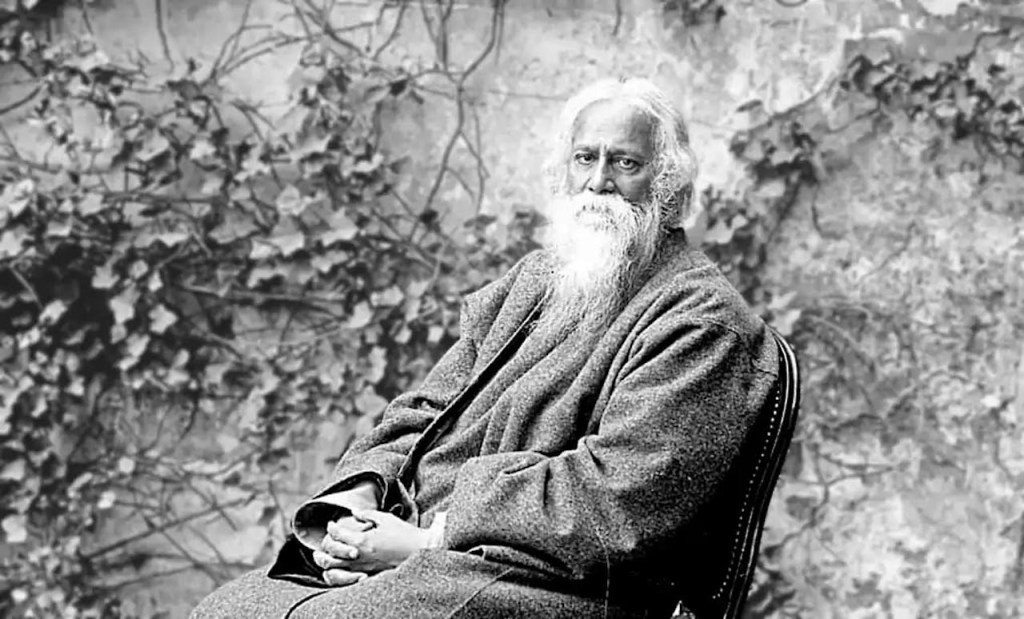

Image: Rabindranath Tagore Beshara Magazine

Life Sketch of Rabindranath Tagore

In 1913, Rabindranath Tagore, Indian Nobel Laureate, won the literature prize for his prose translations of Gitanjali, Bengali for “song offerings.” A true Renaissance man, he served as a poet, social reformer, and founder of a school.

Early Life and Education

Rabindranath Tagore, (in Bengali, Rabīndranāth Ṭhākur), was born May 7, 1861, Calcutta, India, to the religious reformer Debendranath Tagore (1817–1905) and Sarada Devi (1830–1875). Sarada gave birth to fifteen children with Debendranath Tagore [1].

Rabindranath was the youngest of the children and was raised primarily by his oldest sister and servants. His mother fell ill after giving birth to her last child, and she died when Rabindranath was only fourteen years of age.

Tagore came to disdain formal education. He was first enrolled in public education at the Oriental Seminary School in Calcutta. At only seven years of age, he dropped out of school after attending for one month. Students at the school were punished by being beaten with sticks.

After enrolling in the school of Saint Xavier in 1876, he managed to attend for six months but then again left the institution. However, he did retain some pleasant memories of his attendance at Saint Xavier and in 1927, he gifted the school with a statue of Jesus Christ from his personal collection.

Saint Xavier values its relationship with Tagore, despite its brevity, and commemorates his birthday anniversary, even holding their ceremony during the pandemic in 2021:

The principal of the college, Father Dominic Savio, said: “We have decided to remember him on his birthday not only for paying tribute to a true Xaverian, who preached universal humanism but also to get inspiration from his writings, preaching and philosophy, particularly at this trying time”.[2]

Tagore was richly homeschooled by his many accomplished siblings; his brother Hemendranath trained his younger brother in physical culture, having “Rabi” swim in the Ganges and hike through the surrounding hills.

Rabindranath also practiced gymnastics, wresting, and judo, under the watchful eye of his older brother. With other siblings, Tagore studied history, geography, drawing, anatomy, mathematics. Most importantly for his future writing career, he studied Sanskrit and English literature.

Tagore’s contempt for formal schooling was on display when he enrolled in Presidency College but then spent only one day at the school. His philosophy of teaching held that appropriate teaching included fueling curiosity not merely explaining situations.

Founding His Own School

Ironically, Tagore’s later interest in education led him to the founding of his own school in 1901 at Santiniketan (“Peaceful Abode”) in the bucolic countryside in West Bengal. His school was established as an experimental educational institution, which would blend the best features of Eastern and Western traditions in education.

Tagore relocated from Calcutta to reside permanently at his school. In 1921, it became officially known as Visva-Bharati University, an important learning institution still flourishing today. The following is from the school’s mission statement:

The principal of the college, Father Dominic Savio, said: “We have decided to remember him on his birthday not only for paying tribute to a true Xaverian, who preached universal humanism but also to get inspiration from his writings, preaching and philosophy, particularly at this trying time”.[2]

To bring into more intimate relation with one another, through patient study and research, the different cultures of the East on the basis of their underlying unity.

To approach the West from the standpoint of such a unity of the life and thought of Asia.

To seek to realize in a common fellowship of study the meeting of the East and the West, and thus ultimately to strengthen the fundamental conditions of world peace through the establishment of free communication of ideas between the two hemispheres. [3]

Tagore’s keen perception and deep understanding of the areas in which public education had become hopelessly corrupt prompted him to create a learning environment in which his vision of holistic learning could become a reality while continuing to grow and flourish.

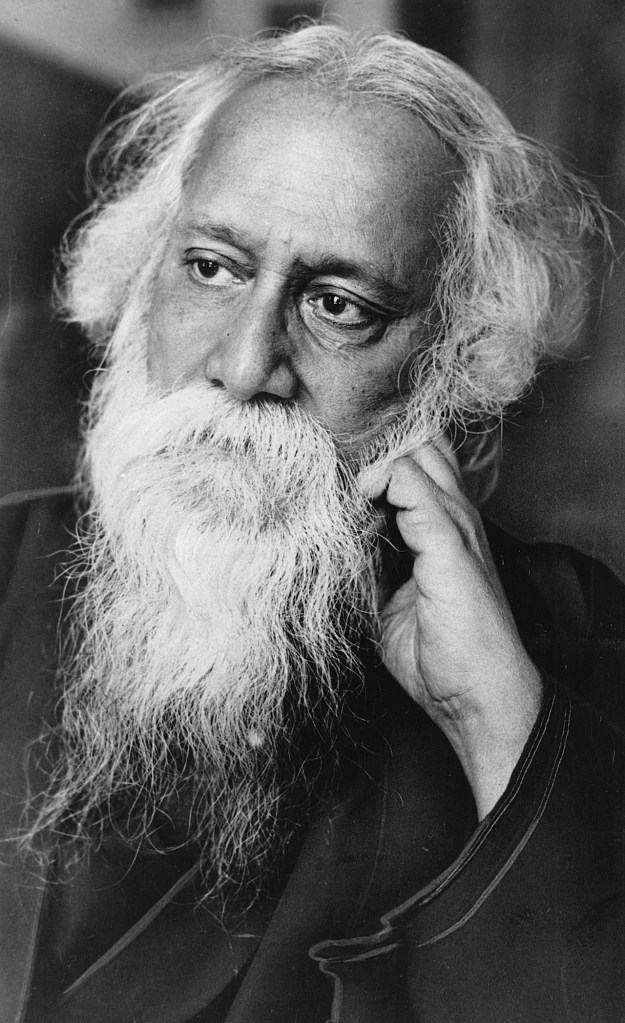

Image: Rabindranath Tagore – Nobel Prize

Nobel Prize for Literature

The English painter and art critic William Rothenstein [4] became deeply interested in the philosophy and writings of Rabindranath Tagore. The painter especially was attracted to Tagore’s prose poems from Gitanjali, Bengali for “song offerings.” The beauty and charm of these poems compelled Rothenstein to suggest to Tagore that he translate them into English so people in the West could appreciate them.

Tagore, following Rothenstein’s advice, translated his song offerings in Gitanjali into English prose renderings. In 1913, Rabindranath Tagore was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature primarily for this volume of poems. Also in 1913, the publishing house Macmillan brought out the hardcover copy of Tagore’s prose translations of Gitanjali.

William Butler Yeats, the greatest Irish poet, also a Nobel Laureate (1923), penned the introduction to Gitanjali. Yeats reports that this volume of poems “stirred [his] blood as nothing has for years.” About Indian culture in general, Yeats opines, “The work of a supreme culture, they yet appear as much the growth of the common soil as the grass and the rushes.”

Yeats’ interest and perusal of Eastern philosophy intensified, and he was particularly moved by Tagore’s spiritual writing. Yeats avers that Tagore’s tradition was one wherein

poetry and religion are the same thing and that it has passed through the centuries, gathering from learned and unlearned metaphor and emotion, and carried back again to the multitude the thought of the scholar and of the noble. [5]

Yeats later composed many poems based on Eastern concepts, although their subtleties at times evaded him [6]. Nevertheless, Yeats deserves credit for advancing the West’s attention and interest in the spiritual essence of those concepts. Yeats further asserts in his introductory piece to Gitanjali,

If our life was not a continual warfare, we would not have taste, we would not know what is good, we would not find hearers and readers. Four-fifths of our energy is spent in this quarrel with bad taste, whether in our own minds or in the minds of others.

Yeats’ decidedly severe appraisal of Western culture quite accurately reflects the mood of his era: the Irish poet’s birth and death dates (1861-1939) sandwiches his life between two bloody Western wars, the American Civil War (1861–1965) and World War II (1939–1945).

Yeats also accurately speaks to Tagore’s achievement as he reports that Tagore’s songs “are not only respected and admired by scholars, but also they are sung in the fields by peasants.” The Irish poet would have been astonished and delighted if his own poetic efforts had been accepted by such a wide spectrum of the populace.

In Yeats’ poem, “The Fisherman,” he creates a speaker who is asserting the need for such an organic, pastoral style of poetry. He is calling for a poetry that will be meaningful for the common folk.

Yeats reveals his contempt for charlatans, while encouraging an ideal that he feels must guide culture and art. Yeats encouraged a style of art that he felt most closely appealed to the culture of the Irish. Thus, the Irish poet comprehended the beauty and simplicity native to the concept of a poetry for the common folk.

Image: Rabindranath Tagore

Sample Poem from Gitanjali

The following prose-poem rendering #7 is representative of the Gitanjali’s form and content:

My song has put off her adornments. She has no pride of dress and decoration. Ornaments would mar our union. They would come between thee and me. Their jingling would drown thy whispers.

My poet’s vanity dies in shame before thy sight. O Master Poet, I have sat down at thy feet. Only let me make my life simple and straight like a flute of reed for thee to fill with music.

This poem unveils a charm that remains humble: it is, in fact, a prayer to soften the poet’s heart to his Belovèd Master Poet (God), without unnecessary words and gestures. A poet steeped in vanity produces only ego-centered poetry, but this guileless poet/devotee seeks only to be open to the simple humbleness of truth that only the Heavenly Father-Creator can bestow upon his soul.

As the Irish poet William Butler Yeats has averred, these songs emerge from a culture in which art and religion have become synonymous. Thus, it comes as no surprise that the offerer of these humble songs is speaking directly to the Divine Belovèd (God) in song after song, and song rendering #7 remains a perfect example.

In the last line of song #7 is a subtle allusion [7] to Bhagavan Krishna. The great yogi/poet Paramahansa Yogananda elucidates the meaning:

Krishna is shown in Hindu art with a flute; on it he plays the enrapturing song that recalls to their true home the human souls wandering in delusion.

Tagore’s employment of religious themes remains a subtle yet integral part of his works. He seldom engages in overtly polemical exposition, only a natural, organic art that inspires even as it educates and entertains.

Renaissance Man

Rabindranath Tagore became an accomplished writer of poetry, essays, plays, and novels. And despite his early disagreeable relationship with schooling, he is also noted for becoming an educator and founder of Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan, West Bengal, India.

Tagore’ many accomplishments renders him a perfect example of a Renaissance man, who is skilled in many fields of endeavor, including spiritual poetry. Despite being a world traveler, Rabindranath Tagore lived most of his life in the same house in which he was born. On August 7, 1941, he died in that same house, three months after his 80thbirthday.

Sources

[1] Editors. “Rabindranath Tagore.” Britannica. Accessed February 17, 2022.

[2] Debraj Mitra. “Rabindranath Tagore’s Birthday Celebrated at Xavier’s.” The Telegraph Online. October 5, 2021.

[3] Official Website of Visva-Bharati University. Accessed February 19, 2023.

[4] William Rothenstein. Rabindranath Tagore. Imperfect Encounter : Letters of William Rothenstein and Rabindranath Tagore, 1911-1941. Semantic Scholar. Accessed January 2, 2024.

[5] Malcolm Sen. “Mythologising a ‘Mystic’: W.B. Yeats on the Poetry of Rabindranath Tagore.” History Ireland. July/August 2010.

[6] Linda S. Grimes. “William Butler Yeats’ Transformations of Eastern Religious Concepts.” Dissertation Abstract. Ball State University. Advisor: Thomas R. Thornburg. 1987.

[7] Paramahansa Yogananda. “Chapter 15: The Cauliflower Robbery from Autobiography of a Yogi.” Hinduwebsite.com. Accessed February 17, 2022.

🕉

You are welcome to join me on the following social media:

TruthSocial, Locals, Gettr, X, Bluesky, Facebook, Pinterest

🕉

Commentaries on Rabindranath Tagore Poems

- Rabindranath Tagore’s Gitanjali #48: “The morning sea of silence…” Rabindranath Tagore’s poem elucidating a metaphorical and metaphysical journey is number 48 in his most noted collection titled Gitanjali. The poet received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913, specifically for that collection.

- Rabindranath Tagore’s “Light the Lamp of Thy Love” Rabindranath Tagore’s poem “Light the Lamp of Thy Love” is a devotional lyric that expresses the speaker’s longing for self-realization. Through colorful imagery, the poem explores themes of transformation, redemption, and the transcendence of human limitation through spiritual awakening.

- Rabindranath Tagore’s “The Last Bargain” Rabindranath Tagore’s “The Last Bargain” focuses on what seems to be an quandary: how is it that a child’s offering of “nothing” to a seeker becomes the “last bargain” as well as the best bargain?

🕉

Share