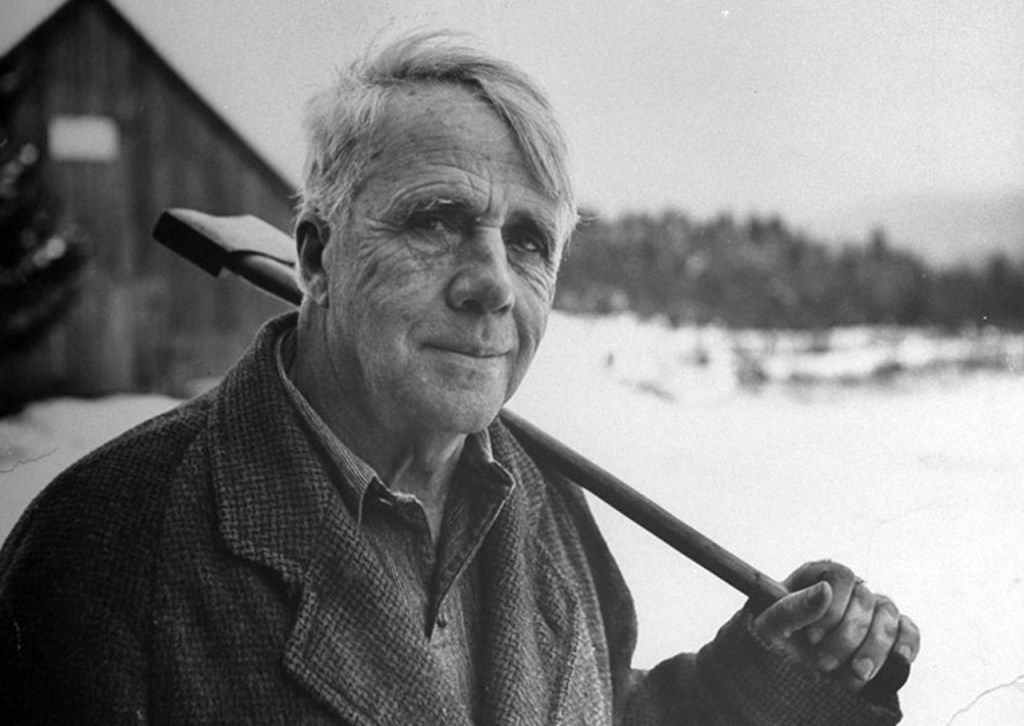

Image: Robert Frost – Library of America

Life Sketch of Robert Frost

Taking his place among luminaries such as Dickinson and Whitman, Frost has remained one of the most widely anthologized American poets of all time. His poems are more complex than simple nature pieces; many are “tricky—very tricky,” as he once quipped about “The Road Not Taken.”

Robert Frost has earned his reputation as one of America’s most beloved poets. The poet holds the honor of being the first American poet to deliver his poems to the assembled celebrants at the 1961 inauguration of the 35th president of the United States of America, John F. Kennedy.

Early Life

Robert Frost’s father, William Prescott Frost, Jr., was a journalist, residing in San Fransisco, California, when Robert Lee Frost was born on March 26, 1874. Robert’s mother, Isabelle, was an immigrant from Scotland.

The young Frost spent the first eleven years of his childhood in San Fransisco. After his father died of tuberculosis, Robert’s mother relocated the family, including his sister, Jeanie, to Lawrence, Massachusetts, where they lived with Robert’s paternal grandparents.

In 1892, Robert graduated from Lawrence High School, where he and Elinor White, his future wife, served as co-valedictorians.

Robert then made his first attempt to attend college at Dartmouth College, but after only a few months, he left school and returned to Lawrence, where he began working a series of part-time jobs [1].

Marriage and Children

Elinor White, who had been Robert’s high school sweetheart, was attending St. Lawrence University when Robert proposed to her. She turned him down because she wanted to complete her college education before she married.

Robert then moved to Virginia, and then after he returned to Lawrence, again he proposed to Elinor, who had now completed her college education. The couple married on December 19, 1895. They produced six children.

Their son, Eliot, was born in 1896 but died in 1900 of cholera; their daughter, Lesley, lived from 1899 to 1983. Their son, Carol, born in in 1902 but committed suicide in 1940.

Their daughter, Irma, 1903 to 1967, battled schizophrenia for which she was confined in a mental hospital. Daughter, Marjorie, born 1905 died of puerperal fever after giving birth. Their sixth child, Elinor Bettina, who was born in 1907, died one day after her birth.

Only Lesley and Irma survived their father. Mrs. Frost suffered heart issues for most of her life. She was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1937 but the following year died of heart failure [2].

Farming and Writing

Robert then again attempted to attend college. In 1897, he enrolled in Harvard University, but because of health problems, he was forced to leave school again. He rejoined his wife in Lawrence. Their second child Lesley was born in 1899.

The family then relocated to a New Hampshire farm that Robert’s grandparents had procured for him. Robert’s farming phase thus began as he strove to farm the land while continuing his writing. The Frost’s farming endeavors continued to result in unsuccessful fits and starts. Frost became well adjusted to rustic life, despite his lack of success as a farmer.

On November 8, 1894, in The Independent, a New York newspaper, Frost’s first poem “My Butterfly” appeared in print. The next dozen years proved to be a difficult period in the poet’s personal life yet a fertile one for his writing. The poet’s writing life was launched in a impressive fashion, and the rural, rustic influence on his poems would set a tone and style for all of his works.

Nevertheless, despite the popularity of his individually published poems, such “The Tuft of Flowers” and “The Trial by Existence,” he could not secure a publisher for his collections of works [3].

Moving to England

In 1912, Frost sold the New Hampshire farm and relocated his family to England. Because of his failure to find a publisher in the US for his collections of poems, he decided to try his luck across the pond.

That moved turned out to be life-line for the young poet and his career. At age 38 in England, Frost found a publisher for his collection A Boy’s Will and soon after for his collection North of Boston.

In addition to securing publishers for his two books, the American poet became acquainted with Ezra Pound and Edward Thomas, two important contemporary poets. Pound and Thomas reviewed favorably Frost’s two book, and thus Frost’s career as a poet was launched.

Frost’s friendship with Edward Thomas became especially important, and Frost has revealed that the long walks taken by the two poet/friends had influenced his writing in a wonderfully constructive manner.

Frost has given credit to Thomas for one of his most famous poems, “The Road Not Taken,” which was influenced by Thomas’ attitude toward the fact of not being able to take two different paths on their long walks.

Returning to America

After World War 1 began in Europe, the Frosts moved back to the United States. Their brief stay in England had sparked useful results for the poet’s reputation, for even in his native country, he was becoming well known and loved.

American Publisher Henry Holt republished Frost’s earlier collections, and then published the poet’s third collection, Mountain Interval, which had been written while Frost was still living in England.

Frost began to experience the pleasing situation of having the same journals, such as The Atlantic, solicit his work, even though they had rejected those same works only a few years earlier.

In 1915, the Frosts purchased a farm, located in Franconia, New Hampshire. Their traveling days had come to and end, and Frost continued his writing career. Frost also taught intermittently at a number of colleges, including Dartmouth, University of Michigan, and especially Amherst College, where he served regularly from 1916 until 1938.

Amherst’s primary library is now the Robert Frost Library, in honor of the long-time educator and poet. Frost also spent most of his summers teaching English at Middlebury College in Vermont.

Frost never completed a university degree, but over his lifetime, he accumulated more than forty honorary degrees. Frost won the Pulitzer Prize four times for his books, New Hampshire, Collected Poems, A Further Range, and A Witness Tree.

Frost labeled himself a “lone wolf” in the world of poetry because he did not follow any current literary movements. His only motivation was to express the human condition in a world of duality.

Frost did not pretend to explain that condition; he sought solely to create his little dramas to reveal the nature of the emotional life in the mind and heart of a human being [4].

First American Inaugural Poet

Robert Frost had intended to star his occasional piece “Dedication” as a preface to the poem that the President-Elect John F. Kennedy had requested for his 1961 inauguration.

But the sun rendered Frost’s reading impossible, so he dropped “Dedication” but continued on to recite “The Gift Outright” from memory.

Introduction with Text of “Dedication”

On January 20, 1961, Robert Frost became the first American poet to deliver a poem at a presidential inauguration. He recited his poem “The Gift Outright” at the swearing in of John F. Kennedy as the 35th president of the United States of America. Frost had also written a new poem to preface his recitation of “The Gift Outright,” but he did not have time to commit his new piece to memory.

At the inauguration, Frost began to read the new piece, but he was unable to see clearly his copy of the poem because of the bright sunlight bouncing off the snow; he managed to stumble through the first 23 lines of the new poem [5]. But then he switched to reciting “The Gift Outright,” which he had by memory.

While Frost’s “Dedication” offers some useful and important historical features, it does reveal some of the fawning exaggeration that occasional poems [6] are often wont to suffer.

Dedication

Summoning artists to participate

In the august occasions of the state

Seems something artists ought to celebrate.

Today is for my cause a day of days.

And his be poetry’s old-fashioned praise

Who was the first to think of such a thing.

This verse that in acknowledgement I bring

Goes back to the beginning of the end

Of what had been for centuries the trend;

A turning point in modern history.

Colonial had been the thing to be

As long as the great issue was to see

What country’d be the one to dominate

By character, by tongue, by native trait,

The new world Christopher Columbus found.

The French, the Spanish, and the Dutch were downed

And counted out. Heroic deeds were done.

Elizabeth the First and England won.

Now came on a new order of the ages

That in the Latin of our founding sages

(Is it not written on the dollar bill

We carry in our purse and pocket still?)

God nodded his approval of as good

So much those heroes knew and understood,

I mean the great four, Washington,

John Adams, Jefferson, and Madison

So much they saw as consecrated seers

They must have seen ahead what not appears,

They would bring empires down about our ears

And by the example of our Declaration

Make everybody want to be a nation.

And this is no aristocratic joke

At the expense of negligible folk.

We see how seriously the races swarm

In their attempts at sovereignty and form.

They are our wards we think to some extent

For the time being and with their consent,

To teach them how Democracy is meant.

“New order of the ages” did they say?

If it looks none too orderly today,

‘Tis a confusion it was ours to start

So in it have to take courageous part.

No one of honest feeling would approve

A ruler who pretended not to love

A turbulence he had the better of.

Everyone knows the glory of the twain

Who gave America the aeroplane

To ride the whirlwind and the hurricane.

Some poor fool has been saying in his heart

Glory is out of date in life and art.

Our venture in revolution and outlawry

Has justified itself in freedom’s story

Right down to now in glory upon glory.

Come fresh from an election like the last,

The greatest vote a people ever cast,

So close yet sure to be abided by,

It is no miracle our mood is high.

Courage is in the air in bracing whiffs

Better than all the stalemate an’s and ifs.

There was the book of profile tales declaring

For the emboldened politicians daring

To break with followers when in the wrong,

A healthy independence of the throng,

A democratic form of right divine

To rule first answerable to high design.

There is a call to life a little sterner,

And braver for the earner, learner, yearner.

Less criticism of the field and court

And more preoccupation with the sport.

It makes the prophet in us all presage

The glory of a next Augustan age

Of a power leading from its strength and pride,

Of young ambition eager to be tried,

Firm in our free beliefs without dismay,

In any game the nations want to play.

A golden age of poetry and power

Of which this noonday’s the beginning hour.

Commentary on “Dedication”

Robert Frost’s poem “The Gift Outright” remains the poem remembered for the inauguration of John F. Kennedy, and it also happens to be a much stronger poem than “Dedication.”

Frost once remarked [7] about his poem “The Gift Outright” that is was “a history of the United States in a dozen lines of blank verse.”

First Movement: Invocation to Artists

Summoning artists to participate

In the august occasions of the state

Seems something artists ought to celebrate.

Today is for my cause a day of days.

And his be poetry’s old-fashioned praise

Who was the first to think of such a thing.

This verse that in acknowledgement I bring

Goes back to the beginning of the end

Of what had been for centuries the trend;

A turning point in modern history.

The speaker seems to be postponing his task of making this inauguration a grand and glorious event by remarking the efficacy and appropriateness of artists contributing to such an occasion. He likens his current effort to past glories of “poetry’s old-fashioned praise” of remarking that certain occasions are bound to point to historical trends.

The speaker’s claims remain rather vague and noncommittal but still leave open the possibility that things will become clearer and more specific as he continues to offer his gems of wisdom.

He claims that what he is doing, bringing verse to event, is as old as the beginning. But that beginning is then sparked by the “beginning of the end”; thus, the speaker is covering himself in case he may be proven wrong.

Second Movement: The Forming of a Nation

Colonial had been the thing to be

As long as the great issue was to see

What country’d be the one to dominate

By character, by tongue, by native trait,

The new world Christopher Columbus found.

The French, the Spanish, and the Dutch were downed

And counted out. Heroic deeds were done.

Elizabeth the First and England won.

The speaker then draws an interesting picture of “colonial” America. He contends that the many nations that have found their progeny on the new shores were battling for dominance, putting forth the question: would France, Spain, or Holland take the lead in heading the American nation?

But then he answers the question by declaring England the winner, as “Elizabeth the First and England won.” Thus, the speaker provides answers to this question of whose characteristics, language, and traits would prevail: America would not adopt French or Spanish or Dutch as its native language; it would be English whose tongue the New World would speak.

Also, one can imagine the “native traits” including English style clothing, manners, and food. The other nations, while welcome, would take their place as an accompanying position.

Third Movement: Tribute to the Founding

Now came on a new order of the ages

That in the Latin of our founding sages

(Is it not written on the dollar bill

We carry in our purse and pocket still?)

God nodded his approval of as good

So much those heroes knew and understood,

I mean the great four, Washington,

John Adams, Jefferson, and Madison

So much they saw as consecrated seers

They must have seen ahead what not appears,

They would bring empires down about our ears

And by the example of our Declaration

Make everybody want to be a nation.

While this movement contains a number of historically accurate statements, it remains rather awkward in its structural execution. The parenthetical—”(Is it not written on the dollar bill / We carry in our purse and pocket still?)”— followed by the line,”God nodded his approval of as good” render their substance less impactful.

That “Latin of our founding sages” refers to “E Pluribus Unum,” (Out of the many, One) and loses it heft when placed as a parenthetical. Robert Frost was a somewhat religious agnostic. That he would claim that God was nodding approval of anything seems a bit out of character sparking a question of sincerity.

Because of Frost’s wholly secular take on the historical founding of a nation— despite the fact that one of the founding principles for founding this nation was religious—the questionable sincerity issue continues to present itself.

This issue is especially evident since the poem is an occasional poems specifically written to celebrate a politician in his ascendency to political office. The tribute to “Washington, / John Adams, Jefferson, and Madison,” whom the speaker designates “as consecrated seers” remains a wholly accurate statement.

And the final two lines appropriately celebrate the document the “Declaration of Independence” which along with the U. S. Constitution remain two of the most important texts ever to exist. The existence of those documents remains important both to the American nation and the world, making “everybody want to be a nation.”

Fourth Movement: Pursuing Life, Liberty, and Happiness

And this is no aristocratic joke

At the expense of negligible folk.

We see how seriously the races swarm

In their attempts at sovereignty and form.

They are our wards we think to some extent

For the time being and with their consent,

To teach them how Democracy is meant.

“New order of the ages” did they say?

If it looks none too orderly today,

‘Tis a confusion it was ours to start

So in it have to take courageous part.

No one of honest feeling would approve

A ruler who pretended not to love

A turbulence he had the better of.

The speaker then engages the issue of immigration to this newly formed nation. It makes perfect sense that folks from all over the world would desire to emigrate from totalitarian, freedom-squelching dictators in their own nations. And it remains quite sensible that they would want to relocate to this new land.

This new land from the beginning embraces freedom and individual responsibility while promising such in those documents delineating the basic human rights of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

The speaker denigrates the notion that only the aristocrats were appreciated and allowed to flourish in this new land. New immigrants may become our “ward,” but that status is only temporary and “with their consent.” In other words, new immigrants can become citizens of our new land of freedom because that new land represents the “[n]ew order of the ages.”

Fifth Movement: A Courageous Nation

Everyone knows the glory of the twain

Who gave America the aeroplane

To ride the whirlwind and the hurricane.

Some poor fool has been saying in his heart

Glory is out of date in life and art.

Our venture in revolution and outlawry

Has justified itself in freedom’s story

Right down to now in glory upon glory.

Come fresh from an election like the last,

The greatest vote a people ever cast,

So close yet sure to be abided by,

It is no miracle our mood is high.

Courage is in the air in bracing whiffs

Better than all the stalemate an’s and ifs.

The speaker then focuses on the very specific event of the Wright Brothers (“the twain”) and their new invention “the aeroplane.” He then asserts that such feats have put the lie to the “poor fool” who thinks that there is no longer any “glory” in “life and art.” He insists that the American adventure story in “revolution and outlawry” has been gloriously vindicated and “justified [ ] in freedom’s story.”

The speaker then offers his take of how this recent election, whose result he is now celebrating, played out. He deems it the “greatest vote a people ever cast”—an obvious exaggeration. Yet, while the election was “close,” it will be “abided by.” The citizenry’s mood is “high,” and that fact is “no miracle.” He then asserts that such a situation arises out of the courage of the nation.

Sixth Movement: The Curse of the Inaugural Poem

There was the book of profile tales declaring

For the emboldened politicians daring

To break with followers when in the wrong,

A healthy independence of the throng,

A democratic form of right divine

To rule first answerable to high design.

There is a call to life a little sterner,

And braver for the earner, learner, yearner.

Less criticism of the field and court

And more preoccupation with the sport.

It makes the prophet in us all presage

The glory of a next Augustan age

Of a power leading from its strength and pride,

Of young ambition eager to be tried,

Firm in our free beliefs without dismay,

In any game the nations want to play.

A golden age of poetry and power

Of which this noonday’s the beginning hour.

In the opening line of this final movement, the speaker alludes to John F. Kennedy’s book, Profiles in Courage—”book of profile tales.” Of course, the inaugural poet in his inaugural poem had to focus on the subject of this occasion, the new president of the United States, whom he is celebrating with his poem.

But then he becomes overly solicitous in his following remarks claiming that this president was a politician who can “break with followers when in the wrong.” The speaker furthers his fawning remarks by suggesting that this administration would be a “democratic form of right divine / To rule first answerable to high design.” This statement boarders on toadying flattery.

Then the puffery in the movement continues with the prediction of a “next Augustan age,” until the final unfortunate lines, “A golden age of poetry and power / Of which this noonday’s the beginning hour.”

Of course, hindsight now confirms that no “golden age” ever resulted for politics or poetry. And this president was assassinated before the completion of his first term in office.

While Frost’s “Dedication” offers some useful commentary, it still fails as a genuine poem. Even as an occasional poem in it final movement, it engages overzealously in exaggerated flattery.

One is reminded that fortunately, this piece did not see the light of day, as Frost was unable to read it as he intended. The poet was spared the drubbing he no doubt would have received had the sunlight not conspired to keep that piece in the dark.

Robert Frost’s “The Gift Outright”

Robert Frost’s “The Gift Outright” became the first inaugural poem, after President-Elect John F. Kennedy asked the famous poet to read at his swearing in ceremony—the first time a poet had read a poem at a presidential inauguration.

Introduction with Text of “The Gift Outright”

On January 20, 1961, John F. Kennedy was inaugurated the 35th president of the United States of America. For the inauguration ceremony, Kennedy had invited America’s most famous poet, Robert Frost, to write and read a poem. Frost rejected the notion of writing an occasional poem, and so Kennedy asked him to read “The Gift Outright.” Frost then agreed.

Kennedy then had one more favor to ask of the aging poet. He asked Frost the change the final line of the poem from “Such as she was, such as she would become” to “Such as she was, such as she will become.”

Kennedy felt that the revision reflected more optimism than Frost’s original. Frost did not like the idea, but he relented for the young president’s sake. Frost did, nevertheless, write a poem especially for the occasion titled “Dedication,” which he intended to read as a preface to “The Gift Outright.”

At the inauguration, Frost attempted to read his occasional poem, but because of the bright sunlight bouncing off the snow, his aging eyes could not see the poem well enough to read it. He then continued to recite “The Gift Outright.”

Regarding the changing of the final line: instead of merely reading the line with the revision Kennedy had requested, Frost stated,

Such as she was, such as she would become, has become, and I – and for this occasion let me change that to –what she will become. (my emphasis added)

Thus, the poet remained faithful to his own vision, while satisfying the presidential request. Robert Frost’s poem, “The Gift Outright,” offers a brief history of the USA, which has just elected and was in the process of inaugurating its 35th president.

The speaker of Frost’s poem, without becoming chauvinistically patriotic, manages to offer a positive view of the country’s struggle for existence, a struggle that can be deemed a gift that the Founding Fathers gave to themselves and the world.

To the question—“Well, Doctor, what have we got—a Republic or a Monarchy?”—regarding the product created by the Constitutional conveners during their meetings from May 25 to September 17, 1787, in Philadelphia, Founder Benjamin Franklin responded, “A Republic, if you can keep it” [8].

The US Constitution became a gift that has kept on giving in the best possible way. It replaced the old, weak Articles of Confederation and kept the nation in tact even during a bloody Civil War, nearly a century later.

The speaker in Frost’s poem offers a brief overview of the American struggle for existence, and he describes that struggle resulting in a Constitution as a gift the Founders gave themselves and to all the generations to follow.

The Gift Outright

The land was ours before we were the land’s.

She was our land more than a hundred years

Before we were her people. She was ours

In Massachusetts, in Virginia,

But we were England’s, still colonials,

Possessing what we still were unpossessed by,

Possessed by what we now no more possessed.

Something we were withholding made us weak

Until we found out that it was ourselves

We were withholding from our land of living,

And forthwith found salvation in surrender.

Such as we were we gave ourselves outright

(The deed of gift was many deeds of war)

To the land vaguely realizing westward,

But still unstoried, artless, unenhanced,

Such as she was, such as she would become.

Robert Frost Reading “The Gift Outright”

At Inauguration

Commentary on “The Gift Outright”

Robert Frost’s inaugural poem offers a glimpse into the history of the country that has just elected its 35th president.

First Movement: The Nature of Possession

The land was ours before we were the land’s.

She was our land more than a hundred years

Before we were her people. She was ours

In Massachusetts, in Virginia,

But we were England’s, still colonials,

Possessing what we still were unpossessed by,

Possessed by what we now no more possessed.

The first movement begins by offering a brief reference to the history of the country over which the new government official would now preside. The speaker asserts that the men and women who had settled on the land, which they later called the United States of America, had begun their experiment in freedom living on the land which would later become their nation, and they would then become its citizens.

Instead of merely residing as a loosely held-together band of individuals, they would become a united citizenry with a name and government shared in common. The official birthdate of the United States of America is July 4, 1776; with the Declaration of Independence, the new country took its place among the nations of the world.

And the speaker correctly states that the land belonged to the people “more than a hundred years” before Americans became citizens of the country. He then mentions two important early colonies, Massachusetts and Virginia, which would become states (commonwealths) after the new land was no longer a possession of England.

Second Movement: The Gift of Law and Order

Something we were withholding made us weak

Until we found out that it was ourselves

We were withholding from our land of living,

And forthwith found salvation in surrender.

During the period from 1776 to 1887, the country struggled to found a government that would work to protect individual freedom and at the same time provide a legal order that would make living in a free land possible. An important first step was the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union [9], the first constitution written in 1777, which was not ratified until 1781.

The Articles failed to provide enough structure for the growing nation, and by 1787, it was deemed that a new, stronger document was needed to keep the country functioning and united. Thus, the Constitutional Convention of 1787 [10] was convened to rewrite the Articles.

Instead of merely writing them, however, the Founding Fathers scrapped the old document and composed a new U.S. Constitution, which has remained the founding set of laws guiding America since it was finally ratified June 21, 1788 [11].

The speaker describes America’s early struggle for self governance as “something we were withholding,” and that struggle “made us weak.” But finally, we found “salvation in surrender,” that is, the Founding Fathers surrendered to a document that provided legitimate order but at the same time offered the greatest possible scope for individual freedom.

Third Movement: The Gift of Freedom

Such as we were we gave ourselves outright

(The deed of gift was many deeds of war)

To the land vaguely realizing westward,

But still unstoried, artless, unenhanced,

Such as she was, such as she would become.

The speaker describes the early turbulent history of his country as a time of “many deeds of war,” which would include the war [12] the early Americans had to fight against England—its mother country—to secure the independence that it had declared and demanded.

But the young nation wholeheartedly gave itself that “gift” of existence and freedom by continuing its struggle and continuing to grow by expanding “westward.” The people of this nation struggled on through many hardships “unstoried, artless, unenhanced” to become the great nation that now—at the time of the poet’s recitation—has elected its 35th president.

Sources

[1] Editors. “Robert Frost.” Poetry Foundation. Accessed March 26, 2023.

[2] Editors. “Who Was Robert Frost?” Biography. Updated: December 1, 2021.

[3] Editors. “Robert Frost at the Farm.” Robert Frost Farm. Accessed March 26, 2023.

[4] Robert P. Eckert, Jr. “Robert Frost in England.” Mark Twain Quarterly. Vol. 3, No. 4 (SPRING, 1940). Via Jstor.

[5] Tim Ott. “Why Robert Frost Didn’t Get to Read the Poem He Wrote for John F. Kennedy’s Inauguration.” Biography. June 1, 2020.

[6] Editors. “Occasional Poem.” American Academy of Poetry. Accessed June 28, 2021.

[7] Maria Popova. “On Art and Government: The Poem Robert Frost Didn’t Read at JFK’s Inauguration.” brainpickings. Accessed July 1, 2021.

[8] Editors. “Benjamin Franklin.” Respectfully Quoted: A Dictionary of Quotations. bartleby.com. Accessed March 26, 2023.

[9] Editors. “Articles of Confederation.” History. October 27, 2009.

[10] Richard R. Beeman. “The Constitutional Convention of 1787: A Revolution in Government.” Interactive Constitution. Accessed March 10, 2021.

[11] NCC Staff. “The Day the Constitution Was Ratified.” National Constitution Center. June 21, 2020.

[12] Curators. “Timeline of the Revolutionary War.” UsHistory.org.

Commentaries on Robert Frost Poems (in process)

- Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken” This poem has been one of the most anthologized, analyzed, and quoted poems in American poetry. It has also remained one of the most misunderstood and thus misinterpreted poems in the English language.

- Robert Frost’s “Birches” Also one of Frost’s most famous poems, “Birches”features a speaker looking back on a boyhood experience that he cherishes and would like to do again. Unfortunately, this “tricky poem” has suffered ludicrous readings that insert onanism into its innocent nostalgia.

- Robert Frost’s “Carpe Diem” The phrase “carpe diem,” meaning “seize the day,” originates with the classical Roman poet Horace. Frost’s speaker offers a different view that questions the usefulness of that idea. This poem offers a sample of the themes and the style in which Frost wrote most of his more successful poems.

- Robert Frost’s “Bereft” Robert Frost’s poem “Bereft” displays one of the most amazing metaphors to be encountered in poetry: “Leaves got up in a coil and hissed, / Blindly struck at my knee and missed.” Like “The Road Not Taken,” however, this poem offers up a tricky feature.

- Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” This poem remains simple, but the repeated phrase, “And miles to go before I sleep,” gives room for Interpretation. Many of Frost’s poems possess a tricky element, and he quipped about “The Road Not Take” being “very tricky.”

🕉

You are welcome to join me on the following social media:

TruthSocial, Locals, Gettr, X, Bluesky, Facebook, Pinterest

🕉

Share