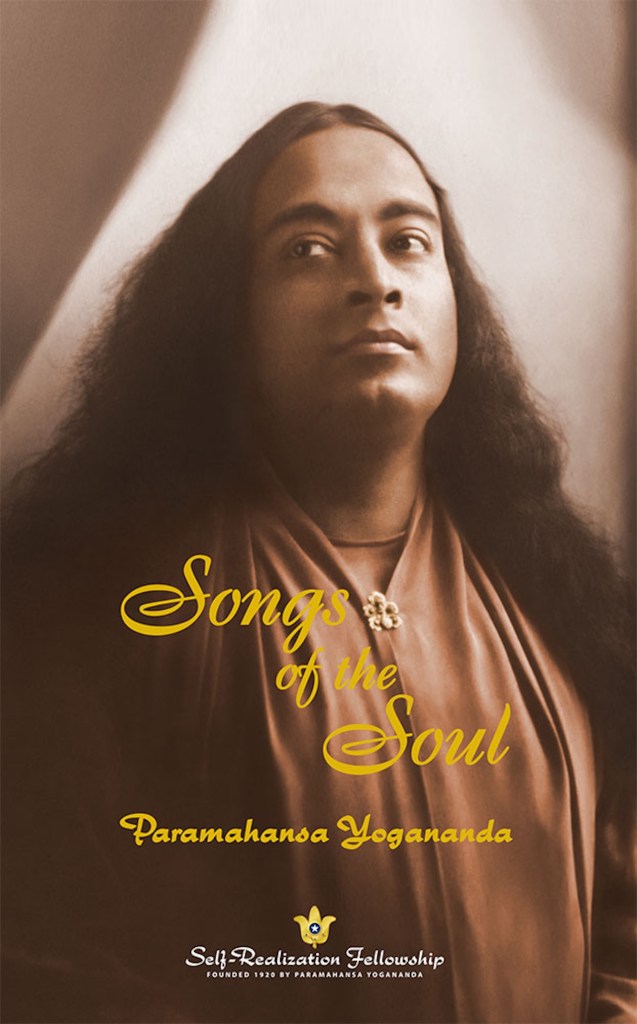

Image: Paramahansa Yogananda’s Song of the Soul

Commentaries on Paramahansa Yogananda’s Songs of the Soul

Each time my father, mother, friends

Do loudly claim they did me tend,

I wake from sleep to sweetly hear

That Thou alone didst help me here.

—from “One Friend”

for Ron Grimes, my soulmate

with whom I travel the spiritual path

About These Commentaries

This collection of personal commentaries is a companion to the book of spiritual poems, Songs of the Soul, written by Paramahansa Yogananda, the “Father of Yoga in the West.”

While these commentaries offer elucidation of each poem, they cannot offer the beauty and majesty experienced by reading the poems themselves.

I have included only an excerpt from each poem preceding each commentary. I, therefore, humbly suggest that you acquire a copy of the great guru’s poems to experience them for yourself, along with my commentaries.

Paramahansa Yogananda’s Songs of the Soul is available at the Self-Realization Fellowship bookstore, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other online outlets, as well as in bookstores everywhere.

These commentaries are my personal responses to the poems in Paramahansa Yogananda’s Songs of the Soul. If they assist any reader in understanding the poetic language on a deeper level, then that is a bonus, for my only purpose is to offer my own personal, humble reading.

Another version of these commentaries resides on HubPages. The first installment is located at Paramahansa Yogananda’s “Consecration.”

Brief Publishing History of Songs of the Soul

The first version of Paramahansa Yogananda’s Songs of the Soul appeared in 1923. He continued to revise the poems during the 1920s and 1930s, and the definitive revision that was authorized by the great guru was published in 1983, featuring many restored lines that had been excised from the first publication of the text.

The 1923 version of the collection of poems appears online at Internet Archive. For my commentaries, I rely on the printed text of the 1983 version; the current printing year for that version is 2014. The 1983 printing offers the final approved versions of these poems.

Special Purpose of the Poems in Songs of the Soul

The poems in Songs of the Soul come to the world not as mere literary pieces that elucidate and share common human experiences as most ordinary successful poems do, but these mystical poems also serve as inspirational guidance to enhance the study of the yoga techniques disseminated by the great guru, Paramahansa Yogananda.

He came to the West, specifically to Boston, Massachusetts, in the United States of America, to share his deep knowledge of yoga through techniques that lead the mind to conscious awareness of God, a phenomenon that he called “self-realization.”

The great guru published a series of lessons that contain the essence of his teaching as well as practical techniques of Kriya Yoga.

His organization, Self-Realization Fellowship, has continued to publish collections of his talks in both print and audio format that he gave nationwide during the 1920s, 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s.

In addition to Songs of the Soul, the great guru/poet offers mystical poetic expressions in two other publications, Whispers from Eternity and Metaphysical Meditations, both of which serve in the same capacity that Songs of the Soul does, to assist the spiritual aspirant on the journey along the spiritual path.

The official website for Paramahansa Yogananda’s Self-Realization Fellowship offers further information about the Lessons and Kriya Yoga.

Image: Book Cover – Songs of the Soul

Commentaries

This section features the commentaries, one for each of the 101 poems in Songs of the Soul. Each commentary is preceded by a brief introduction and excerpt from the poem.

1. “Consecration”

In the opening poem, titled “Consecration,” the speaker humbly offers his works to his Creator. He offers the love from his soul to the One Who gives him his life and his creative ability, as he dedicates his poems to the Divine Reality or God.

Introduction and Excerpt from “Consecration”

Paramahansa Yogananda, the great guru/poet and founder of Self-Realization Fellowship, known as the “Father of Yoga in the West,” dedicates his book of mystical poems, Songs of the Soul, to his earthly father and consecrates it by offering it to his Heavenly Father (God—the Divine Creator). In dedicating his collection to his earthly father, the great guru writes,

Dedicated

to my earthly father,

who has helped me in all my spiritual

work in India and America

The first poem appearing in the great yogi-poet’s book of spiritual poems is an American (innovative) sonnet, featuring two sestets and a couplet with the rime scheme AABBCC DDEFGGHH.

The first sestet is composed of three rimed couplets; the second sestet features two rimed couplets and one unrimed couplet that occupies the middle of the sestet.

This innovative form of the sonnet is perfectly fitted to the subject matter and purpose of the Indian yogi, who has come to America to minister to the waiting souls, yearning for the benefits of the ancient yogic techniques in which the great guru will instruct them.

The ancient Hindu yogic concepts offer assistance to Westerners in understanding their own spiritual traditions, including the dominant Christianity of which many are already devotees.

Excerpt from “Consecration”

At Thy feet I come to shower

All my full heart’s rhyming* flower:

Of Thy breath born,

By Thy love grown,

Through my lonely seeking found,

By hands Thou gavest plucked and bound . . .

*The spelling, “rhyme,” was introduced into English by Dr. Samuel Johnson through an etymological error. As most editors require the Johnson-altered spelling of this poetic device, the text of Songs of the Soul also adheres to that requirement featuring the spelling, “rhyming.” However, when I employ that term in my commentaries, I use the original spelling, “rime.”

Commentary

These spiritual poems begin with their consecration, a special dedication that offers them not only to the world but to God, the Ultimate Reality and Cosmic Father, Mother, Friend, Creator of all that is created.

First Sestet: Dedication of Poetic Effort

The speaker proclaims that he has come to allow his power of poetry to fall at the feet of his Divine Belovèd Creator. He then avers that the poems as well as the poet himself are from God Himself.

The Divine Belovèd has breathed life into the poems that have grown out of the speaker’s love for the Divine. The speaker has suffered great loneliness in his life before uniting with his Divine Belovèd.

The spiritually striving speaker, however, has earnestly searched for and worked to strengthen his ability to unite with the Divine Creator, and he has been successful in attaining that great blessing.

The speaker/devotee is now offering that success to his Divine Friend because he knows that God is the ultimate reason for his capabilities to accomplish all of his worthwhile goals. As he feels, works, and creates as a devotee, he gives all to God, without Whom nothing that is would ever be.

Second Sestet: Poems for the Divine

In the second sestet, the speaker asserts that he has composed these poems for the Belovèd Creator. The collection of inspirational poetic works placed in these pages contains the essence of the guru-poet’s life and accomplishments made possible by the Supreme Spirit.

The writer asserts that from his life he has chosen the most pertinent events and experiences which will illuminate and inform the purpose of these poems.

The speaker is metaphorically spreading wide the petals of his soul-flowers to allow “their humble perfume” to waft generously.

He is offering these works not merely as personal effusions of shared experience for the purpose of entertainment or self-expression but for the upliftment and soul guidance of others, especially for his own devoted followers.

His intended audience remains the followers of his teachings, for he knows they will continue to require his guidance as they advance on their spiritual paths.

The Couplet: Humbly Returning a Gift

The speaker then with prayer-folded hands addresses the Divine directly, averring that he is in reality only returning to his Divine Belovèd that which already belongs to that Belovèd. He knows that as a writer he is only the instrument that the Great Poet has used to create these poems.

As the humble writer, he takes no credit for his works but gives it all to the Prime Creator. This humble poet/speaker then gives a stern command to his Heavenly Father, “Receive!”

As a spark of the Divine Father himself, this mystically advanced speaker/poet discerns that he has the familial right to command his Great Father Poet to accept the gift that the devotee has created through the assistance of the Divine Poet.

2. “The Garden of the New Year”

In “The Garden of the New Year,” the speaker celebrates the prospect of looking forward with enthusiastic preparation to live “life ideally!”

Introduction and Excerpt from “The Garden of the New Year”

The ancient tradition of creating New Year’s resolutions has situated itself in much of Western culture, as well as Eastern culture. As a matter of fact, world culture participates in this subtle ritual either directly or indirectly.

This tradition demonstrates that hope is ever present in the human heart. Humanity is always searching for a better way, a better life that offers prosperity, peace, and solace.

Although every human heart craves those comforts, each culture has fashioned its own way of achieving them. And by extension, each individual mind and heart follows its own way through life’s vicissitudes.

The second poem is titled “The Garden of the New Year.” This poem dramatizes the theme of welcoming the New Year, using the metaphor of the garden where the devotee is instructed to pull out “weeds of old worries” and plant “only seeds of joys and achievements.”

The pulling out of weeds from the garden of life is a perfect metaphor for the concept of a New Year’s resolution. We make those resolutions for improvement and to improve we often find that we must eliminate certain behaviors in order to instill better ones.

The poem features five unrimed versagraphs*, of which the final two are excerpted.

Excerpt from “The Garden of the New Year”

. . . The New Year whispers:

“Awaken your habit-dulled spirit

To zestful new effort.

Rest not till th’ eternal freedom is won

And ever-pursuing karma outwitted!”

With joy-enlivened, unendingly united mind

Let us all dance forward, hand in hand,

To reach the Halcyon Home

Whence we shall wander no more . . .

*The term, “versagraph,” is a conflation of “verse paragraph,” the traditional unit of lines for free verse poetry. I coined the term for use in my poem commentaries.

Commentary

This poem is celebrating living life “ideally,” through changing behavior that has limited that ability in the past.

First Versagraph: Out with the Old and in with the New

The speaker is addressing his listeners/readers as he asserts that the old year has left us, while the New Year is arriving.

The old year did spread its “sorrow and laughter,” yet the New Year holds promises of brighter encouragement and hope. The New Year’s “song-voice” offers grace to the senses, while commanding, “Refashion life ideally!”

This notion is universally played out as many people fashion New Year’s resolutions, hoping to improve their lives in the coming year.

Because most people are always seeking to improve their situations, they determine how to do so and resolve that they will follow a new path that will lead to a better place.

Second Versagraph: Abandoning the Weed to Plant New Seeds

In the second versagraph, the speaker employs the garden metaphor to liken the old problematic ways to weeds that must be plucked out so that the new ways can be planted and grow.

The speaker instructs the metaphoric gardener to pull out the weeds of “old worries” and in their place plant “seeds of joys and achievements.”

Instead of allowing the weeds of doubt and wrong actions to continue growing, the spiritual gardener must plant seeds of “good actions and thoughts, all noble desires.”

Third Versagraph: The Garden Metaphor

Continuing the garden metaphor, the speaker advises the spiritual aspirant to “sow in the fresh soil of each new day / Those valiant seeds.” After having sown those worthy seeds, the spiritual gardener must “water and tend them.”

The perfect metaphor for one’s life is the garden with its life-giving entities as well as its weeds. As one tends a garden, one must tend one’s life as well to make them both the best environment for life to thrive.

By careful attention to the worthy, good seeds of attitudes and habits, the devotee’s life will become “fragrant / With rare flowering qualities.”

Fourth Versagraph: New Year as Spiritual Guide

The speaker then personifies the New Year as a spiritual guide who gives sage advice through whispers, admonishing the devotees to employ real effort to wake up their sleeping spirit that has become “habit-dulled.”

This new spiritual guide advises the spiritual aspirant to continue struggling until their “eternal freedom” is gained.

The spiritual searchers must work, revise their lives, and continue their study until they have “outwitted” karma, the result of cause and effect that has kept them earth-bound and restless for aeons.

The beckoning New Year always promises a new chance to change old ways. But the seekers must do their part. They must cling to their spiritual path, and as soon as they veer off, they must return again and again until they have reached their goal.

Fifth Versagraph: A Benediction of Encouragement

The speaker then offers a benediction of encouragement, giving the uplifting nudge to all those spiritual aspirants who wish to improve their lives, especially their ability to follow their spiritual paths.

The speaker invites all devotees to “dance forward” together “With joy-enlivened, unendingly united mind.” The speaker reminds his listeners that their goal is to unite their souls with their Divine Beloved Who awaits them in their “Halcyon Home.”

And once they achieve that Union, they will need no long venture out into the uncertainty and dangers as they exist on the physical plane.

The New Year always holds the promise, but the spiritual aspirant must do the heavy lifting to achieve the lofty goal of self-realization.

3. “My Soul Is Marching On”

This amazing poem, “My Soul Is Marching On,” offers a refrain which devotees can chant and feel uplifted in times of lagging interest and seeming spiritual dryness.

Introduction and Excerpt from “My Soul Is Marching On”

The poem, “My Soul Is Marching On,” offers five stanzas, each with the refrain, “But still my soul is marching on!” The poem demonstrates the soul’s power in contrast with the weaker powers of entities from nature.

For example, as strong as the light of the sun may be, it vanishes at night, and will eventually be extinguished altogether in the long, long run of aeons of time.

Unlike those seemingly forceful, yet ultimately, much weaker physical, natural creatures, the soul of each individual human being remains a strong, vital, eternal, immortal force that will keep marching on throughout all time—throughout all of Eternity.

Devotees who have chosen the path toward self-realization may sometimes feel discouraged as they tread the path, feeling that they do not seem to be making any progress.

But Paramahansa Yogananda’s poetic power comes to rescue them, giving in his poem a marvelous repeated line that the devotee can keep in mind and repeat when those pesky times of discouragement float across the mind.

Included here are the epigram and first two stanza of the poem, “My Soul Is Marching On.”

Excerpt from “My Soul Is Marching On”

Never be discouraged by this motion picture of life. Salvation is for all. Just remember that no matter what happens to you, still your soul is marching on. No matter where you go, your wandering footsteps will lead you back to God. There is no other way to go.

The shining stars are sunk in darkness deep,

The weary sun is dead at night,

The moon’s soft smile doth fade anon;

But still my soul is marching on!

The grinding wheel of time hath crushed

Full many a life of moon and star,

And many a brightly smiling morn;

But still my soul is marching on! . . .

Commentary

Before beginning his encouraging drama of renewal, Paramahansa Yogananda offers an epigram that prefaces the poem by stating forthrightly its intended purpose. In case the reader may fail to grasp the drama of the poetic performance, the epigram will leave no one in doubt.

The Epigram: A Balm to the Marching Soul

The great guru avers that there is no other reality but the soul’s forward march. Despite all circumstance to the contrary, the soul will, in fact, continue its march.

The devotee simply has to come to realize that fact that all “wandering footsteps” return to their home in the Divine. The guru then states unequivocally, “There is no other way to go.”

This amazing, inspiring statement culminates in the refrain that allows the devotee to take into mind a chant for upliftment anytime, anywhere it is needed.

First Stanza: The Soul Marches on in Darkness

The speaker begins by asserting that the bright bodies of the stars, sun, and moon are often hidden. The stars seem to sink into the black backdrop of the sky, or even remain hidden by day, as if never to be seen again, yet other times, they are completely invisible.

The largest dominant star of all—the sun—also seems to completely vanish from the sight of world-weary inhabitants of planet Earth. The sun seems to be “weary” as it has crossed the diurnal sky and then sinks out of sight.

The moon whose glow remains less bright compared to the sun, nevertheless, also fades out of sight. All of these bright orbs of such tremendous magnitude glow and fade, for they are mere physical beings.

The speaker then adds his marvelous, encouraging claim that becomes his refrain—”But still my soul is marching on!” The speaker will continue repeating this vital assertion as he dramatizes his poem to encourage and uplift devotees whose spirits may from time-to-time lag.

This refrain will then ring in their souls and urge them to keep marching because their souls are already continuing that march.

Second Stanza: Nothing Physical Can Halt the Spiritual

The speaker then reports that time has already smashed moons and stars and obliterated them from existence. Many cycles of creation and recreation have come and gone from the annals of eternity.

That eventuality remains the nature of physical creation: it emerges from the depths of the body of the Divine Creator and then later is taken back into that Divine Body, disappearing as if they had never been.

But regardless of what happens on the physical level, the soul remains an existing Entity throughout Eternity. The soul of each individual continues its journey. It makes no difference on which planet it may appear; it may continue from planet to planet, if necessary, as it marches back to its Creator.

The soul will continue to “stand unshaken amidst the crash of breaking worlds” because that is the nature of the indestructible soul, the life energy that informs each human being.

That soul will continue its march to the Divine, despite all cosmic activity. Nothing can prevent the soul’s forward march, nothing can stop the marching soul, and nothing can hinder that march. The refrain shall again and again ring in the mind of the devotee who has begun this march to self-realization.

Third Stanza: The Evanescence of Nature

The speaker then reports on other natural phenomena. Marvelous, beautiful flowers have offered their colorful blooms to the eyes of humankind, but then they invariably fade and shrivel up to nothingness. The evanescence of beauty remains a conundrum for the mind of humankind.

Like the beauty yielding flowers, the gigantic trees offer their “bounty” for only a while, and then they too sink into nothingness. The naturally appearing entities that feed the human mind as well as the human body all mysteriously come under “time’s scythe,” appearing and disappearing again and again.

But the soul again remains in contrast to these wonderful natural entities. The soul continues its eternal march, unlike the outer physical realities of flowers and trees. The human soul will continue its march, as will the invisible souls of those seemingly vanishing nature’s living beings.

The refrain must take hold in the mind of the devotee, who in times of lagging interest and self-doubt will chant its truth and become re-invigorated.

Fourth Stanza: As Physical Life Fades, The Soul Continues Unabated

All of the great emissaries sent by the Divine Creator continue to speed by. Vast swaths of time also speed by as creation seems to remain on a collision course with ultimate disaster.

The human being must remain in a perpetually vigilant state of mind just to remain alive in this dangerous and pestilent-filled world. Even human against human remains a continued concern as “man’s inhumanity to man” prevails in very age in every nation of planet Earth.

But the speaker is not only referring to the small planet at a short period of time; he is speaking cosmically of the entire history of all Creation.

He is averring that being born a human being at any time in history brings that individual soul into the same arena of struggle. As each human being lets fling his arrows in battle, the individual finds that all of his “arrows” have been used up. He finds his life ebbing away.

But again, while the physical body remains the battle ground of trials and tribulations, the soul is unaffected. It will continue on its path back to its Divine Haven, where it will no longer need those arrows. The devotee will continue to chant this truth again and again to spark his march to greater heights.

Fifth Stanza: The Refrain Must Remain

The speaker has observed that his fight with nature has been a fierce one. Failures have blocked his way. He has experienced the ravages of death’s destruction. He has had to face obstructions blocking “his path.”

All of nature has conspired to “block [his] path.” Nature has always been a challenging force, but the human being who has determined to overcome the ravages of nature will find that his “fight” is stronger than that of nature, despite the fact that nature remains a “jealous” power.

The soul continues to march to its home in God, where it will never again have to face the fading of beautiful light, the vanishing of colorful flowers, the failures that obstruct and slow one’s pace.

The soul will continue to march, to study, to practice, to meditate, and to pray until it at last experiences success, until it as last finds itself totally awake in the arms of the Blessed Divine Over-Soul, from which it has come.

The devotee will continue to hear that amazingly uplifting line and continue to know that his/her “soul is marching on!”

4. “When Will He Come?”

How to stay motivated in pursuing the spiritual path remains a challenge. This poem, “When Will He Come?,” dramatizes the key to meeting this spiritual challenge.

Introduction and Excerpt from “When Will He Come?”

Perhaps today is not going well, and you feel indifferent about your work and your progress. You might begin to think about how you have not been giving enough time and effort to your spiritual progress.

You might then begin to feel deeply depressed and begin to judge your motives harshly. And finally, you decide that you do not deserve to reach your spiritual goals because of your laxity.

You realize that days have gone by, and you have taken care of every detail of your life, but you have neglected your soul. You have veered off your spiritual path and are dallying in the ditch of delusion.

Of course, you know what the problem is and you know how to solve it, so you turn back to your spiritual studies.

You pick a spiritual poem to uplift your thinking. Likely there is no better poem than the one that answers your immediate question as you wonder when the Lord will finally appear to you.

This poem contains the exact message that you need right now: “Even if you are the sinner of sinners, / Still, if you never stop calling Him deeply / In the temple of unceasing love, / Then He will come.”

The poem uplifts you because it simply reminds you to get out of that ditch and back on the road to your goal. You have thought you could not continue, and you have become convinced that Spirit will never come to you, but this inspired spiritual poet’s metaphors dramatically tweak your thoughts back to your goal.

Excerpt from “When Will He Come?”

When every heart’s desire pales

Before the brilliancy of the ever-leaping flames of God-love,

Then He will come.

When, in expectation of His coming,

You are ever ready

To fearlessly, grieflessly, joyously

Burn the faggots of all desires

In the fireplace of life,

That you may protect

Him from your freezing inner indifference,

Then He will come . . .

Commentary

These seven stanzas work to uplift the devotee’s lagging mood and urge it on to greater effort on the path to soul-realization.

First Stanza: The All-Consuming Flame of Spirit

Humanity finds itself needing and wanting a myriad of things of this world. Those things are both tangible or material and intangible or spiritual.

Even in those who are not spiritually inclined, the mind still craves nourishment such as is offered through studying and learning. The impulse to read widely comes from a hungry mind that wishes to know more about the world we live in.

Along the way, however, as these human hearts and minds continue to gather the things of this world, they may suddenly realize that none of those things has the power to make them truly and lastingly happy or can even offer a modicum of permanent comfort and joy.

It is at this point most folks are introduced to the value of a spiritual life: that only the Divine Belovèd can offer everything that the physical, material world cannot.

All of the accumulated earthly desires will eventually lead only dullness and suffering. However, in the first stanza of this poem, devotees are reminded that Spirit’s love is great like “ever-leaping flames.” Such “brilliancy” they must realize will cause every desire of the human heart to pale in comparison.

And all they have to do is keep their attention and concentration on their spiritual routine on the path. A devotee may wonder how s/he could have ever given in to doubt, and yet s/he has read only the opening stanza.

Second Stanza: A Temporary Spacing

The second stanza continues to remind devotees of their own role in finding Spirit, in getting this blessing to come to them: those little pale desires amount to a “freezing inner indifference” that all devotees must burn “fearlessly, grieflessly, joyously” in the “fireplace of life.”

Of course, devotees already know this is true, but they sometimes do temporarily forget. Thus, the purpose of these uplifting, spiritually forward-thrusting poems can be fulfilled as devotees continues to live in their message and be guided by their wisdom.

Daily life becomes routine, and as the initial enthusiasm over beginning a spiritual path wanes, the devotee may find herself in this period of spiritual dryness.

Devotees are urged to continue by reading and rereading their spiritual works and most importantly to continue with their spiritual routines including meditation and prayer.

The speaker of this poem continues to cast the contrast between “desire” and the marvelous achievement to be possessed after quieting desire that continues to eat away at one’s soul.

Third Stanza: Constancy Assures His Ultimate Arrival

Stanza three continues to remind devotees: When Spirit is certain of the devotee’s utmost attention, when the Divine Belovèd knows that the devotee will ever keep her/his mind focused on soul, when nothing else can claim the steadfast heart of the devotee who gives total devotion to his/her spiritual life, “Then He will come.”

It does seem somewhat puzzling that the human heart and mind do not seem to learn that half-heartedly doing anything, whether physically or spiritually oriented, is bound to lead to failure.

If one is studying to become a lawyer, half-hearted attention to one’s studies will not result in success, and obviously that fact is operative in every endeavor.

The same applies to the spiritual path: one must remain on the path with attention focused on the goal in order to succeed.

Fourth Stanza: Ignoring the Hopeless for the Hopeful

But even though devotees may mentally take in these ideas, seekers may still feel easily oppressed by life, may still become moody and feel powerless, and thus may wonder if they can really change enough so that Spirit will come to them and remain permanently.

The demand is quite simple, yet often not so easy to accomplish. But devotees have been assured by the great guru that they can accomplish their spiritual goal, if they continue to love God, stick to the path, and serve willingly in any capacity for which they have an aptitude.

Fifth Stanza: Concentrating the Mind on the Goal

But the mind is stubborn and will fight against the devotee’s best effort, telling him/her that it does not matter how much hope the individual entertains, the devotee will remain weak and therefore undeserving of Spirit. Paramahansa Yogananda insists that

if the devotee switches his thoughts from failure to success and believes strongly that the Lord is on His way to the devotee, then the Divine will, in fact, appear to the striving devotee.

Yes, a great solace is remembering the power of the soul. Greater than the body that changes daily and the mind that flits every which way is the soul that is ever united with Spirit already.

All each individual has to do is get out of that ditch and continue on down his/her path and refuse to listen to the opposition, i.e., the Devil or Satan, that would keep the devotee’s mind earthbound committed to the rounds of karma and reincarnation.

Sixth Stanza: When Nothing Else Can Claim the Mind and Heart

Then, the great leader instructs that wandering mind: “When He shall be sure nothing else can claim you, / Then He will come.”

Again and again, the guru continues to remind the wandering mind and soul of his followers to keep focused on the goal, and do not let trivia block you from your Divine Beloved.

When the Divine Goal is all that remains in the concentrated mind of the devotee, that devotee can be assured of success. But each individual must remember the Creator expects the devotee to be mindful that nothing else must claim his/her attention.

The devotee must put his/her whole heart and mind into the studies and devotions to reap the benefits.

Seventh Stanza: The Sinner Becomes the Seeker

The great guru then assures his devotee that even the greatest of sinners can gain heaven, simply by abandoning his/her indifferent ways and by continuing to rely upon the Divine Reality. The sinner must not think of himself as a sinner but as one who is a seeker of the Divine Creator.

The former sinner must keep calling on the Divine Beloved, taking the beloved name again and again, chanting love for the Only Reality.

And after diving into this inspired song of the soul written just for the devotees by this great Spirit-illumined poet, they are prepared to enter again that “temple of unceasing love” where they will be ready to greet Him when He comes.

Poetic Encouragement

The sentiment and guidance of the poems in Songs of the Soul are there for the devotee.

Regardless of how downtrodden each individual may feel, whether tormented by trials and tribulations, tested by karmic factors, no matter how fearful, if the practicing devotee remains steadfastly on the path, and if the devotee keeps hope alive in his/her heart, the Divine Belovèd is sure to come into one’s life.

The reassurance that calming the dogs of desire can be of helpful assistance as one travels that path to spirit is offered repeatedly in these poems.

They help one return again and again to the traits that one needs for soul-realization, which includes the coming of the Divine into one’s consciousness.

The great guru is not instructing his devoted followers to ignore their material duties. He states often that one must take care of the body and mind as well as the soul and must perform those duties that involve family.

The devotee who shirks familial responsibilities is also likely to shirk his/her spiritual duties.

The key is to find balance, to perform one’s material duties with full attention and then as soon as those duties are completed to return the mind to the spiritual goal.

These poems shine a light on how to live in this world and yet not become so attached to the things of this world that such attachment interferes with spiritual goals.

5. “Vanishing Bubbles”

Worldly things are like bubbles in the sea; they mysteriously appear, prance around for a brief moment, and then are gone.

This speaker dramatizes the bubbles’ brief sojourn but also reveals the solution for the minds and hearts left grieving for those natural phenomena that have vanished like those bubbles.

Introduction and Excerpt from “Vanishing Bubbles”

“Vanishing Bubbles” features five variously rimed stanzas. The irregularity of the rime-scheme correlates perfectly with the theme of coming and going, appearing and disappearing, existing and then vanishing. Also, the frequent employment of slant-rime and near-time support that main theme as well.

The poem’s theme dramatizes the evanescence of worldly objects under the spell of maya, and the speaker expresses a desire to understand where these things come from and where they go after they seem to disappear.

This age-old conundrum of life remains a pervasive feature of every human mind—born into a fascinating yet dangerous world, seeking to understand, survive, and enjoy.

Excerpt from Vanishing Bubbles

Many unknown bubbles float and flow,

Many ripples dance by me

And melt away in the sea.

I yearn to know, ah, whence they come and whither go—

The rain drops and dies,

My thoughts play wild and vanish quick,

The red clouds melt into the skies;

I stake my purse, I’ll slave all life, their motive still to seek . . .

Commentary

The things of this world are like bubbles in the ocean—appearing and then disappearing as if they had never been.

First Stanza: Coming and Going in the Mayic Drama

In the first stanza, the speaker states that many things come and go, and he would like to know both where they come from and to where they vanish.

The speaker metaphorically compares these worldly objects to “bubbles,” indicating that their existence is tenuous, ephemeral, and that they are in reality only temporary appearances on the screen of life.

The bubbles remain “unknown,” for they seem to appear as if by magic. The observer cannot determine how, where, or why they so magically appear.

The speaker continues to describe the bubbles as things that, “dance with me / And melt away into the sea.” The waves of the sea that cause little watery bubbles to bounce around the swimmer serve as a useful metaphor for all the worldly things that are passing through a fragile existence on their way to who knows where.

By extension, the observer may also think of every physical object in existence as a magical production because the observer/thinker cannot think his way to the origin of all those bubble-like things.

Even each human life may be compared to a vanishing bubble; from the time of birth to the moment of death, the exact locus of the human soul cannot be understood with the human brain.

Thus all of human existence along with the things that humans experience, including the grandest scale items such as mountains, stars, universes, may be metaphorically expressed as vanishing bubbles.

Second Stanza: The Evanescence of Natural Phenomena

The speaker then reports that rain drops appear and die away as quickly as they approached, noting again another natural phenomenon that comes quickly and leaves just as quickly.

But then the speaker adds that his thoughts also come and go with great speed. As if with the rain, the speaker’s thoughts arrive and then flee.

The nature of thought adds to the mystery of all things; while there are physical, seemingly concrete items one perceived as reality, there is also the subtle, abstract realm where thoughts, feelings, ideas, and notions of all kinds appear and disappear and seem to possess an equal portion of reality.

Again, making his observation as concrete as possible, the speaker then reports that “red clouds” seem to dissolve into the skyey surrounding; the rain vanishes and the cloud vanishes, leaving the speaker to desire ever so strongly to know the why and wherefore of such actions.

As the human mind takes in the drama of its physical surroundings, it not only observes the actions but begins to wonder about the nature of those things, where they come from, where they are going, and for what purpose.

And as wishes, desires, and feelings intrude upon the mind, the speaker becomes even more determined to understand the drama which he is observing.

Most human beings, especially those with a contemplative penchant, at some point in their lives feel that they would give all their hard-earned wealth just to understand some of the mysteries that continue to play in their lives.

The human heart and mind especially yearn to understand why suffering and pain must play such a large part in the drama of life.

And the “vanishing bubble” metaphor yields a deep metaphoric meaning for those hearts and minds that have suffered great loss in life.

But just as the mind cannot answer to what it loses, it cannot answer from what it has gained. Winning and losing become part of the same phenomenon tossed by the sea of life with all of the vanishing bubbles.

Just so, the speaker thus vows to “stake [his] purse” and “slave all [of his] life” to find out why these things behave as they do.

The difference between this dramatic speaker and the average human observer is the intensity with which the former craves such knowledge.

This speaker would give all his wealth, and in addition, he will work—even “slave”—all his life to know the secrets behind all of these mysterious bubbles.

Third Stanza: The Intense Desire to Know

The speaker then notes that even some of his friends have vanished, but he asserts that he knows he still has their love. He, thus, is imparting the knowledge that the unseen is the part of creation that does not vanish.

The physical bodies of his friends must undergo the vanishing act, but their love does not, because love is entrenched in the immortality of the soul.

As the speaker broaches the spiritual concepts, including love, he begins to point to the reality of existence where things do not behave as vanishing bubbles.

He supports that great claim that love is immortal, and although his friends have, as bubbles do, appeared and then disappeared behind that seemingly impenetrable screen, that love that he harbored for them and they for him cannot disappear and cannot behave bubble-like.

The speaker then avers that his “dearest thoughts” also can never be lost. He then points out that the “night’s surest stars” that were “seen just above” have all “fled.”

Objects as huge and bright as stars come and go, but his own thoughts and love do not. He has thus reported that it is the concrete things that seem to come and go, while the abstract is capable of remaining.

Fourth Stanza: All Matter of Sense-Appealing Nature

In the fourth stanza, the speaker offers to the eye and ear a list of nature’s creatures, such as lilies, linnets, other blooming flowers with sweet aromas, and bees that are “honey-mad.”

These lovely features of nature once appeared on the scene under shady trees, but now only empty fields are left on the scene. As the little wavelets and rain and the stars appeared and then vanished, so did these other phenomena.

The speaker chooses those natural features that life offers in order to report beauty. Flowers along with their scent appeal to both eye and nose.

It is, of course, the senses that are piqued by those natural features, and the human mind, like the “honey-mad” bee becomes attached to the things of the world.

By pointing out the fact that all life’s phenomena appear and then disappear, the speaker, at the same time, is pointing out that it is the spiritual aspect of life that remains eternally.

While the scent of the flower along with their beauty will grace the vision and sense of smell briefly, love and beautiful thoughts may grace the mind and soul eternally for they are the features that retain the ability to remain.

Fifth Stanza: Evanescent Images of Entertainment

The speaker again refers to the evanescent images of “bubbles, lilies, friends, dramatic thoughts.” He then reports that they play “their parts” while they “entertain.”

The speaker then dramatically proclaims that after they vanish, they exist only “behind the cosmic screen.” They do not cease to exist, however; they merely change “their displayed coats.”

Instead of the physical world’s mayic drama of sight and sound, these once worldly presences become “quiet” for they are “concealed.”

But the important, uplifting thought that accompanies the spiritual reality of all phenomena is that they do not truly vanish; they “remain.”

The scientific law of the conservation of energy, as well as the spiritual law of immortality, proclaim their eternal existence.

Again, the speaker has demonstrated that nothing that exists ever, in fact, ceased to exist. The vanishing of things is just the delusion of maya.

Thus because of the great desire to retain all those beautiful features of life, the human mind becomes attracted to and attached to only the acts that lead to true understanding beyond the reach of maya.

6. “The Screen of Life”

“The Screen of Life” dramatizes the mayic dance of life with all its many activities and myriad natural objects that continually come and go.

Introduction and Excerpt from “The Screen of Life”

The poem, “The Screen of Life,”features five versagraphs. The drama emphasizes the vital importance of understanding the delusive nature of the natural world and realizing the reality of the life behind the “screen.”

This colorful poem dramatizes the dance of maya that stirs life with all its many activities and myriad natural objects that so mysteriously continue to appear and then vanish.

Excerpt from “The Screen of Life”

When dawn breaks the spell of darkness

And roses bloom;

When little pleasures all dance round you,

And fickle festivity sings

Of babes newborn (in future sure to die);

When fortune laughs

And praise weaves garlands

And glory makes the crown;

When on all sides men shout your praises

And thousands follow —

You see His hands showering blessings . . .

Commentary

Featuring the interplay of many activities and the objects of nature, this drama plays out like a mayic dance.

First Versagraph: Beauty in the Light of Day

The speaker catalogues items and events that occur after “dawn breaks the spell of darkness.” In the light of day, the individual observes beauty when “roses bloom.”

People experience “little pleasures” that “dance . . . around [them].” The speaker remarks that “fickle festivity sings / Of babes newborn.”

The celebratory atmosphere is “fickle” because that newborn is “sure to die,” even if the death may occur far “in future.” But individuals will go on experiencing praise from others and “fortune” will “laugh.”

This teeming life full of gifts comes to the devotees from the Divine, Who quietly operates the cosmic projector that throws all the images upon the screen of life, and those who look will “see His hands showering blessings.”

Second Versagraph: The Essence of Joy Remains

Even in seasons when life seems to lie dormant, when the rose is without its beautiful blossoms and lush green leaves, even in the midst of snow, the essence of “budding joy” exists “in every twig.”

While joy exists in the activity of experiencing the dawn, it also exists “in waiting” for that “streak of dawn in the dark.” Each pair of opposites contains within it equal joy before the Lord.

Third Versagraph: The Necessity of Opposition

The speaker then examines the nature and the need for the pairs of opposite in the physical world of maya. Without “persecution,” one would not be able to realize the joy of praise.

Without having to go through a period of expectancy, the achievement of a goal would be less joyous. It is the “uncertain darkness” that causes “each little flame of joy” to “burn[ ] brighter.”

While it is human nature to disdain one state and exalt another, the ability to transcend human nature requires a new way of understanding the purpose of unwelcome things and acts.

Fourth Versagraph: Demonstrations of Delusion

Above all, it is important to understand and realize that the images projected upon this screen of earth life demonstrate delusion not “true Life”: “Behind the unreal motion pictures of things seen / Unfolds the real drama.”

Using the metaphor of the motion picture, the speaker reveals that the sense-experienced existence consists of mere “shadows” “lined with light.”

But instead of sinking into melancholy with the news that sense experience is delusion, the speaker helps his listeners understand that “Sorrows bulge with joy. / Failures are potent with determination for success, / Cruelties urge the instinct to be kind.” The bad is not meant to cause harm but to encourage and motivate for the good.

Fifth Versagraph: Awakening in Solitude

The speaker reveals that when the human mind is occupied with the things of this world, especially those that are deemed pleasant and desirable, these things “hide [the Divine Beloved’s] presence.”

But when those things “all are gone,” and the devotee’s mind observes “solitude,” and there is no one left “shaking hands with you,” then “[the Divine] comes to take your hand.” The Blessèd Reality comes after all else has abandoned one.

7. ”Shadows”

Although a “shadow” takes on the form that is standing between it and a light source, it has no reality of its own; it is only the illusion of a form, an airy nothingness, making it a perfect metaphor for the delusion of Maya, variously called “Satan” and the “Devil” in the West.

Introduction and Excerpt from “Shadows”

According to Paramahansa Yogananda, the power of delusion is very strong. A human being is a soul who has a body and a mind, but the power of delusion makes humans think that they are just minds and bodies, and many people tend to think that perhaps the soul is a religious fiction, concocted for the clergy to gain control over the behavior of their minions.

The deluded mind coupled with the solid body convinces humankind that its main reality exists in them. But according to spiritual leaders and teachers, humanity is deluded by maya, the principle of relativity, inversion, contrast, duality, or oppositional states. Maya’s nameis “Satan” in the Old Testament and is referred to as the “Devil” in Christianity.

Jesus Christ colorfully described the mayic devil: “He was a murderer from the beginning, and abode not in the truth, because there is no truth in him. When he speaketh a lie, he speaketh of his own, for he is a liar and the father of it” (King James Version, John 8:44).

Paramahansa Yogananda explains that maya is a Sanskrit word meaning “the measurer,” a magical power in creation which divides and manipulates the Unity of God into limitations and divisions. The great guru says, “Maya is Nature herself—the phenomenal worlds, ever in transitional flux as antithesis to Divine Immutability.”

The great yogi/poet further defines the mayic force by explaining that the purpose of maya is to attempt to divert humankind from Spirit to matter, from Reality to unreality. The great guru further explains,

Maya is the veil of transitoriness of Nature, the ceaseless becoming of creation; the veil that each man must lift in order to see behind it the Creator, the changeless Immutable, eternal Reality.

Paramahansa Yogananda has instructed his devotee-students regarding the workings of the mayic concept of delusion. He often employs useful metaphoric comparisons filled with colorful images.

Excerpt from “Shadows”

Beds of flowers, or vales of tears;

Dewdrops on buds of roses,

Or miser souls, as dry as desert sands;

The little running joys of childhood,

Or the stampede of wild passions;

The ebbing and rising of laughter,

O the haunting melancholy of sorrow . . .

These, all these, but shadows are . . .

(Please note: This poem appears in Paramahansa Yogananda’s Songs of the Soul, published by Self-Realization Fellowship, Los Angeles, CA, 1983 and 2014 printings. A slightly different version of this commentary appears in my publication titled, Commentaries on Paramahansa Yogananda’s Songs of the Soul.)

Commentary on “Shadows”

Jesus Christ described the devil as a murderer and a liar because there is no truth in him. The character/force, called “Satan” in the Old Testament and the “devil” in Christianity, is labeled Maya in Hinduism and yogic philosophy.

First Movement: Maya Similar to Shadows

Beds of flowers, or vales of tears;

Dewdrops on buds of roses,

Or miser souls, as dry as desert sands;

The little running joys of childhood,

Or the stampede of wild passions;

The ebbing and rising of laughter,

O the haunting melancholy of sorrow

A beautiful and revealing example of Paramahansa Yogananda’s dramas featuring maya can be found in this poem. The poem’s first fifteen lines offer a catalogue of pairs of opposites: “bed of flowers,” the first image encountered, is a positive one that readers can visualize as colorful beauty and possibly fragrant smells wafting from the flowers, while “vale of tears” denotes a negative tone of sadness and sorrow.

Then the two images, “Dewdrops on buds of roses, / Or miser souls, as dry as desert sands,” offer again two oppositional pairs, the beauty and life of rosebuds with dew on them contrasts with the aridity of selfishness.

Two further images, “little running joys of childhood, / Or the stampede of wild passions,” contrast innocence with violent emotions. Additionally, the “ebbing and rising of laughter, / Or the haunting melancholy of sorrow” contrast happiness and sadness.

Second Movement: Desire is Will-o-the Wisp

There is an important, interesting break in this pattern with the following lines:

The will-o-the wisp of our desire,

Leading only from mire to mire;

The octopus grip of self-complacency

And the time-beaten habits

While human desire sometimes leads humankind astray from “mire to mire,” human beings may also suffer from their own self-inflicted inertia that prevents them from changing their error-strewn path as their self-complacency and habits hold them in an octopus-like grip.

Both of these pairs are negative. One could speculate about why the poet let these negatives remain without countering them with positives as he did in the other catalogued pairs.

While those two negatives may seem to imbalance the poem, they serve the useful purpose of offering the strong hint that the extremely attractive power of maya causes humanity to mistakenly feel that the world has more negative than good qualities.

Third Movement: Shadows Only for Entertainment and Education

The next two pairs, however, return to the positive/negative pattern: a newborn infant’s first cry vs the death rattle and excellent health of the body vs degenerating diseases.

Then the final six lines aver that all of these experiences of the senses, mind, and emotion are nothing more than “shadows.” They are merely the forces of maya—seen by humanity on the cosmic mental screen.

But instead of allowing human hearts and minds to take from all this that the unreality of maya amounts to airy nothingness, the great spiritual leader enlightens all who encounter his marvelous teachings, to the fact that those shadows contain many shades from dark to light, and those “shadows” are not meant to hurt and discourage the children of the Divine Creator but to serve as a prompt, in order to entertain, educate, and enlighten them.

8. “One That’s Everywhere”

The speaker in “One That’s Everywhere” reveals that Divine Omnipresence strives to reveal Itself through all creatures, even the inanimate.

Introduction and Excerpt from “One That’s Everywhere”

The great spiritual leader, Paramahansa Yogananda, composed many amazing, divinity-inspired poems that inspire and uplift all who are blessed to hear them. One need not be a follower of the great guru’s teachings to understand, appreciate, and benefit from these beautiful, spiritually blessed compositions.

The great guru’s Metaphysical Meditations and Whispers from Eternity are also filled with pieces that guide and inspire as they accompany the devotee on the path to self-realization through the meditation techniques created and offered by the great guru.

This poem features two variously rimed stanzas. The speaker celebrates all natural creatures, including language-blessed humankind. The great guru’s poem reveals that Divine Omnipresence strives to reveal Itself through all creatures, even the so-called inanimate.

All of nature asserts itself from a divine origin. However, because the other creatures remain without language and a definite manner for clear communication, they do not reach the level of capabilities that the human being does.

The complex brain of each human individual that retains the ability to create such a complex and clear system of communication bespeaks the special creation that the human being has undergone through evolution.

Excerpt from “One That’s Everywhere”

The wind plays,

The tree sighs,

The sun smiles,

The river moves.

Feigning dread, the sky is blushing red

At the sun-god’s gentle tread . . .

Commentary

The speaker in this poem is colorfully revealing that Divine Omnipresence strives to reveal Itself through all creatures, even the inanimate.

First Stanza: Varied Creations of Nature

In the first stanza, the speaker begins with deliberation by cataloguing a short list of nature’s entities all coupled with their own special activity: wind playing, tree sighing, sun smiling, and river moving. These varied creations of nature offer the human individual a vast field for thought and wondrous amazement about the natural environment.

This speaker interprets the activities in playful and colorful ways. For example, instead of observing mundanely that the wind blows, his cheerful, creative mind interprets, “the wind plays.” Similarly, instead of merely averring that the sun shines, he offers the unique perspective that “the sun smiles.” The association of “sun” and “smiles” is now quite a widespread phenomenon.

To remark about the largest natural feature of humankind’s field of vision, the speaker offers an expansive line: “Feigning dread, the sky is blushing red / At the sun-god’s gentle tread.” The beauty of the sky becomes intense and palpable through this marvelous interpretation of events.

The triple rime, dread-red-thread, multiplies the phenomenal effect of sun’s rays as they paint the sky. The speaker then dramatizes the daily occurrence of planet Earth transforming from dark to light: “Earth changes robes / Of black and starlit night / For dazzling golden light.”

Second Stanza: Expressing Individuality

Referring to Mother Nature as “Dame Nature,” the speaker reports that this metaphoric lady of nature enjoys decking herself out in fabulous colors that humanity observes as the “changing seasons.”

The speaker then proclaims that “the murmuring brook” attempts to convey “hidden thought” that an unseen, inner spirit brings to the flowing water. This deeply-inspired, observant speaker then reveals, “The birds aspire to sing / Of things unknown that swell within.”

These linguistically mute creatures of nature all are motivated by the unseen, unheard, omnipresent Divinity, about which they strive to articulate in their own unique manner. But it is humankind, who “first speaks in language true.”

While the other natural creatures, also made in the image of the Divine, strive to express their own individuality as they sing of their inner spirit, only the human creature has been blessed with the ability to create and employ a fully formed system of communication.

Only the human being is capable of expressing the Divine in a conscious way. Human individuals are able to speak loudly and clearly and “with meaning new.” All natural creatures, however, are inspired by the divine, but their expression of the great spirit remains only partial.

It is a great blessing, therefore, to reach the status of being born in human form, for in that blessed form the human being is allowed to “fully declare / Of One that’s everywhere,” or state that God, the great Creator, exists in all of creation.

9. “Where I Am”

The great yogi/poet, founder of Self-Realization Fellowship, dramatizes the spiritual journey in his poems. They uplift the mind and direct it toward the Divine Reality or God. This poem offers that same upliftment with the answer to a common question regarding the Divine Reality.

Introduction and Excerpt from “Where I Am”

In “Where I Am,” the Speaker of the poem is the Blessèd, Divine Creator or God. And in this poem, God tells His listener exactly where He is. God is in the soul of each individual because each human being is a unique expression, or spark, or the Divine Creator. One need not acquire union with the Divine Belovèd, but one does have to learn to realize that fact.

Excerpt from “Where I Am”

Not the lordly domes on high

With tall heads daring clouds and sky,

Nor shining alabaster floors,

Nor the rich organ’s awesome roar,

Nor rainbow windows’ beauty quaint —

Colossal chronicle told in paint —

Nor pure-dressed children of the choir,

Nor well-planned sermon,

Nor loud-tongued prayer

Can call Me There . . .

Commentary

As in the other poems in this collection, in “Where I Am,” the great yogi/poet is dramatizing the spiritual journey. Those poems uplift the mind and direct it toward the Divine Reality or God.

First Movement: Not Drawn by Ornate Beauty

The poem opens with the Divine Belovèd describing the ornate beauties of a cathedral that will not necessarily draw His presence. Despite the ornate beauty and grandeur of this cathedral, the Speaker says He will not come there drawn by this material beauty alone.

Then after listing a catalogue of other items that make clear He is describing a majestic church, the Speaker says He will not be summoned by polished sermons and high-toned pleas.

Second Movement: Beautiful but Physical Buildings too Small

The Divine Belovèd reports that He will not enter a “richly carven door” through with only vanity and pride have entered. He will, however, come unseen and unrealized. The fancy features that offer only outward allure remain too small for “My large, large body.”

The Belovèd Lord cannot be tempted by physical beauty alone. All the marble and polished altars in the world cannot bring the Divine Presence if the soul is not tuned to His essence.

Third Movement: Only Attracted by the Soul

The celestial Speaker shows a clear preference for the simplicity of nature: “On grassy altar small — / There I have My nook.” Even ruined temples and a “little place unseen” are preferable if “A humble magnet call” of the devotee’s soul attracts Him.

The final versagraph reveals the place where God always wants to “rest and lean”: in the heart of the true seeker who is “A sacred heart / Tear-washed and true.” Such a heart draws “Me with its rue.”

The Speaker tells us that He takes no bribes—strength, wealth, beautiful, expensive cathedrals, and well-rehearsed ceremonies cannot lure God, unless they are accompanied by the deep desire for truth.

Examining One’s Life

The great ancient Greek philosopher/teacher Socrates said that the unexamined life is not worth living. The nineteenth century American poet/essayist/thinker Henry David Thoreau went to Walden Pond so he could live deliberately.

Both men of deep thought are telling us that this life has meaning and purpose. They believed that living a proper life means more than going through the motions of a daily grind without stopping to muse about the meaning that grind has for each of us.

The result of this idea—of examining our lives with deliberation—leads one to a path of spirituality. Spirituality motivates the human being to seek not only physical needs but also the needs of the mind and of the soul. Our spirituality compels us to commit to a life that allows us to flourish as we seek to understand all the mysteries that life places before us.

The question regarding the location of “God” finds the human mind’s lack of imagination a culprit in its failure to offer a satisfying answer. The great guru Paramahansa Yogananda’s direct yet simple answer to that question offers all of humankind a balm.

Guiding the Imagination Challenged of the World

Unlike the great worldly thinkers of the planet, however, the great guru is able to dramatize God’s location for the stumbling eyeless of the world. His vision far exceeds that of such philosophers as Socrates or Thoreau because as an avatar he possesses true wisdom, being united with God in soul.

In Paramahansa Yogananda’s poem, “Where I Am,” God tells us where He is: in the “sacred heart / Tear-washed and true,” and “the distant broken heart / Doth draw Me, e’en to heathen lands: / And My help in silence I impart.”

10. “In Stillness Dark”

The speaker in this poem is dramatizing the results of calming the body and mind and thus allowing the spiritual eye to come into full view on the screen of the mind, the same location experienced in dreams.

Introduction and Excerpt from “In Stillness Dark”

The poem, “In Stillness Dark,” features two stanzas; the first consists of ten lines of scatter rime, AABCDDEFGG, while the second stanza offers thirteen lines of cluster rimes, AAABBBBCCDEED. This style of rime scheme is exactly appropriate for the poem’s theme, deep meditation.

Beginning yoga meditators find their efforts come in fits and starts until they have mastered the yogic techniques that lead to the necessary stillness required for precise vision. The speaker is creating a little drama that features the journey of devotees as they practice the yogic methods, leading to peace, quiet, and stillness for the ultimate viewing of the vitally important Kutastha Chaitanya, or spiritual eye.

The spiritual eye or Kutastha Chaitanya appears in the three sacred hues of gold, blue, and white. A ring of gold circles a field of blue, at the center of which pulsates a white pentagonal star. The spiritual eye, or eye of God, appears to the deeply mediating devotee. That devotee then is able to have wonderful, divine experiences:

After the devotee is able at will to see his astral eye of light and intuition with either closed or open eyes, and to hold it steady indefinitely, he will eventually attain the power to look through it into Eternity; and through the starry gateway he will sail into Omnipresence. —from “Penetrating the Spiritual Eye” online at The Royal Path of Kriya Yoga

As the speaker in this poem avers, “Apollo droops in dread / To see that luster overspread / The boundless reach of the inner sky.” The spiritual eye puts all lesser light to shame with its brilliance.

Excerpt from “In Stillness Dark”

Hark!

In stillness dark —

When noisy dreams have slept,

The house has gone to rest

And busy life

Doth cease its strife —

The soul in pity soft doth kiss

The truant flesh, to soothe,

And speaks with mind-transcending grace

In soundless voice of peace . . .

Commentary

The speaker in “In Stillness Dark” describes the marvelous outcome that results from calming the body and mind, thus allowing the spiritual eye to become visible on the screen of the mind.

First Stanza: Communion with the Soul

The speaker begins by commanding the meditating devotee to listen carefully to his admonitions. He is instructing the devotee to be aware of what he is going to tell about the magic of becoming still at night in preparation for deep communion with the Divine.

The enlightened speaker is explaining that as the metaphorical house of the soul, the body, goes to sleep to rest, busy dreams also become quiet. As “house” metaphorically represents the body, and at the same time, it literally represents a soul’s residence.

Thus, when “busy life” calms down at night it “cease[s] its strife.” After home life has settled down for the night and the body becomes calm, the devotee may quiet the mind in preparation for the profundity of silent communion with the soul.

During that quiet time, the soul becomes aware of itself; the peace of the soul automatically causes the “truant flesh” to be “soothe[d].” The soul “speaks with mind-transcending grace,” and the “soundless voice” of the soul offers rest and peace to the body.

As the body becomes still, its muscles, heart, and lungs become quiet. Instead of the noisy, busyness with which the physical processes keep the mind stirred, the absence of that motion allows the beauty and sanctity of the soul to shine forth. This process leads to the ability to meditate in order to meet that coveted goal of God-union, or self-realization. The self is the soul, and to realize the soul is humankind’s greatest duty.

Second Stanza: Watching with Care

The speaker commands the meditating devotee to peer through the “walls of sleep.” While “peep[ing]” through those “transient fissures,” the devotee must take care not to “droop” and not to “stare,” but to simply to carefully watch.

The devotee must remain relaxed, not falling asleep nor straining as s/he watches for the “light of the spiritual eye, seen in deep meditation.” The speaker poetically refers to that spiritual eye as “the sacred glare,” which is “ablaze and clear.” The light, because it seems to appear on the screen of the mind in the forehead, does so “in blissful golden glee” as it “flash[es] past [the meditating devotee].”

The light of the spiritual eye puts “Apollo” to shame with its brilliance: “Ashamed, Apollo droops in dread.” The “luster overspread” is not that of the physical cosmos; thus, it is not the sun in the physical sky, but instead exists in the “boundless reach of the inner sky.”

The speaker dramatizes the act of achieving the magnificent result of deep meditation that leads to communion with the Divine. Through calming the physical body and the mind, the devotee allows the energy from the muscles to move to the spine and brain where true union with Divinity is achieved.

The ultimate goal of self-realization or God-union achieved by meditation remains ineffable. God cannot be described as one describes physical objects such as trees, rivers, tables, or curtains, or other human bodies. One might think of the difference in terms of body and mind. We can see a human body; we cannot see a human mind. But the importance of the mind is without doubt.

The mind creates beyond the physicality of all things seen and experienced. Because of the ineffability of the nature of God, soul, and even such familiar terms as love, beauty, and joy, the poet who wishes to explore that nature must do so with metaphoric likenesses. Only a God-realized individual can perform that poetic act with surety and direct purpose.

11. “Silence”

The poem, “Silence,” dramatizes the importance and power of silence in allowing the meditating devotee to connect with his/her inner Divine Glory.

Introduction and Excerpt from “Silence”

The poem, “Silence,” features four tightly crafted stanzas. The author has appended the following note to the lines, “They hear its call / Who noise enthrall”:

I.e., those who practice yoga techniques of meditation, which enable the mind to disconnect itself from sensory distractions, thus freeing it to experiences perceptions of the Indwelling Glory.

This note reveals the poem’s theme, while offering another wondrous name for the Nameless, Whom many simply call God. Paramahansa Yogananda’s finely crafted poem, “Silence,” features a drama of the vitality and power that silence brings, as it allows the meditating devotee to unite with the blessed Divinity within, residing as the soul.

Excerpt from “Silence”

The earth, the planets, play

In and through the sun-born rays

In majesty profound.

Umpire Time

In silence sublime

Doth watch

This cosmic match . . .

Commentary

The speaker in “Silence” is revealing the nature, power, and rôle of silence in the devotee’s struggle for self-realization or God-union.

First Stanza: Beyond Earth Awareness

The speaker begins by taking the reader’s attention beyond earth-bound awareness, remarking that the earth and other planets all participate in a drama bathed by the sun, and that drama, which proceeds like a game, is “[i]n majesty profound.” “Time” plays a rôle similar to an “umpire,” watching “in silence sublime” as the “cosmic match” proceeds.

When creating dramatic scenes from ineffable phenomena, speakers and writers must employ metaphoric likenesses from nature, including personification of abstract concepts such as “time.” Allowing “time” to perform the function of an umpire adds colorful depth as well as understanding of relationships in the ineffable dramatic presentation.

Second Stanza: The Name Unpronounceable

The speaker then explains that the creator of this heavenly match between the sun and the planets performs according to “His will.” The name of this Creator, Who is “The Author of the wondrous game,” cannot be correctly and completely pronounced. Although His children invent names for their Creator, they are unable to invent one name that can encompass all that such an Author must be.

There is simply no name that can be completely useful in labeling the entire cosmos and all of its inhabitants and entities. The pantheistic claim that God is everything makes an accurate statement, but it remains impossible to think about, and thus name, everything all at once.

All names for such an entity are deficient, and therefore unable to be spoken, except in fragments. The concept that the Divine cannot be known by the mind but can be realized by the soul eliminates the deficiency of humankind’s remaining unable to speak authoritatively the name of its Creator.

This wondrous “Author,” however, directs “without a noise.” And humankind can be thankful that as He works, He does so as He takes no notice or retribution against humankind’s ungratefulness, and instead forgives all “Unkindness” rendered by His unrealized children.

The human mind is given to judging, evaluating, and denigrating without sufficient evidence, but the Ultimate Judge holds no grudges for humankind’s errors. The Ultimate Judge simply hands down His rulings made with perfect knowledge and continues on.

Third Stanza: Muted Method of Correction

Despite the seeming obscurity of the Author of this game of life, every created child of the Author-God hears with the ear of conscience even though that conscience does not speak loudly.

Human beings are capable of perceiving that they have transgressed divine laws by the consequences they suffer thereafter; for example, when one overeats, one suffers an uncomfortable stomach, and breaking any law, divine or human, has unpleasant consequences from which the transgressor should learn to change behavior.

Through an indirect and somewhat muted method of correction, the Divine Father allows His children the freedom of will to make their mistakes and then learn from those errors.

Without such freedom, the human mind and heart would be little more than automatons. Instead, those minds and hearts are directed through silent instruction and guidance that remain infallible yet malleable as afforded by individual karma.

Similar to the laws of physics, moral law remains more obvious and compelling because it is infused in the design of nature. A very young child may likely not know beforehand that throwing an object up into the air will result in its immediate return to the ground.

But after the child has experienced the act of tossing an object into the air and finding that it does not remain there but returns to its downward position, s/he will have learned about the nature of gravity and should thereafter behave accordingly.

Thus, it is with the relationships between individuals, where the “Golden Rule” should hold sway, for its obvious glad results for all involved.

Fourth Stanza: Taming the Tiger Heart

In the final stanza, the speaker brings together metaphorically the various transgressions of human behavior that can be overcome through the “powerful silence of unspoken words.”

As noted, the Divine does not speak directly as a parent would directly instruct a child through language, but by meditating and “disconnecting” one’s attention “from sensory distractions,” the devotee who seeks to transform his life, to “tame” his “tiger” body, and “maim” his “failure’s talons,” may do so by freeing his attention from “sensory distractions.”

By contacting the inner silence, the human mind and heart learn to connect with the profound and infallible guidance that permeates every created being. As the heart seeks freedom to feel and the mind seeks freedom to express thoughts, the individual becomes more and more aware of the deep wisdom gained through stillness and silence.

Freedom from physical traumas and mental tortures is necessary for living a balanced and harmonious life. Freedom from all trials and tribulations including doubt, fear, and anxiety becomes necessary for walking the spiritual path that leads to the goal of ultimate soul freedom. After that soul freedom is achieved, the devotee can perceive that unspoken name as that “Indwelling Glory.” The Unnamable emerges as the true reality.

12. “The Noble New”

The theme of “The Noble New” is individualism; the speaker is urging the devotee not to be dragged down by a herd-mentality in journeying toward self-realization.

Introduction and Excerpt from “The Noble New”

The speaker of “The Noble New” extends eight loving commands to devotees in an octet that consists of eight movements in two quatrains.

The first quatrain features two riming couplets, and second quatrain has the traditional rime scheme of an Elizabethan sonnet, ABAB. The great guru praised the United States of America as a land of opportunity and freedom. He admired the business acumen and technological spirit of America.

While loving his native land of India dearly with its emphasis on spirituality, Paramahansa Yogananda always made it clear that the spiritual East and the industrious West were both necessary for advancement on the path to self-realization or God-union. The great spiritual leader praised individuality and always cautioned against blindly following the majority which leads the seeker down the path of stagnation.

Excerpt from “The Noble New”

Sing songs that none have sung,

Think thoughts that ne’er in brain have rung,

Walk in paths that none have trod,

Weep tears as none have shed for God . . .

Commentary

New ways of thinking and behaving do not belong only to the radical, antiestablishment element of society. The spiritual aspirant should also remain an individual, engaged in his/her own critical thinking in order to remain an original thinker, who can accomplish new feats for the world and for God.

First Movement: Unique Songs

The speaker first instructs the devotee to sing his own unique songs to the Divine. Most people are content to listen to worldly music and learn to sing only the songs that others sing.

While in the very beginning, this kind of imitation can help develop the singer’s skill, after the devotee becomes mature in his craft and his belief system, he no longer needs the guide of imitation.

Instead of singing to fellow human beings, the devotee sings only to the Divine, and these songs grow out of the unique relationship the individual has with his Divine Belovèd.

Second Movement: New Pathways of Thought

So much of humankind’s endeavors are mere repetition of what others have accomplished and so many of the thoughts that each person entertains are simply a version of what others have thought for centuries.

Most citizens of Western Civilization have relegated religion and the spiritual life to one day a week, coupled with a few holidays each year. But the devotee who craves more of the Divine than what fits into that small framework must make every effort to think of Divinity all of the time, or in the beginning as much as possible.

Thinking those thoughts to which the speaker refers means thinking about the Divine Belovèd all the time and very intensely at certain times—during meditation, prayer, and chanting.

Third Movement: A Road Truly Less Traveled