Shakespeare Sonnets: The Muse Sonnets 74—126

Shakespeare Sonnet 74 “But be contented: when that fell arrest”

Sonnet 74 “But be contented: when that fell arrest”reveals the speaker’s awareness of the triune nature of the human body’s composition and that nature’s relationship to art creation, as he continues the theme on life’s brevity.

Introduction and Text of Sonnet 74 “But be contented: when that fell arrest”

Sonnet 74 “But be contented: when that fell arrest”begins with the coordinating conjunction “but” to signal its connection to sonnet 73 (see “Shakespeare Sonnet 73 ‘That time of year thou mayst in me behold’” at HubPages) as the speaker insists that despite life’s brevity and finality, art can act as a kind of defense again annihilation.

If the speaker can portray his life, his loves, his interests honestly and clearly enough, he will in a sense be creating for his life a kind of immortality that the purely physical level of being can never emulate.

The very spirit of art is what lives on after the death of the artist, whose spirit is captured in that art, if the artist has genuine talent and the ability to fulfill its promise. Themed sub-sequences appear in the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence. Such is the case with sonnet 74, which is a companion to sonnet 73 and sonnet 75 “So are you to my thoughts as food to life.”

In sonnet 73, the speaker metaphorically dramatizes the aging process to emphasize the nature of deep love and its preservation in art: knowing that life on the physical level exists only briefly renders the ability to love and capture its qualities in art even more intense.

Sonnet 74 “But be contented: when that fell arrest”

But be contented: when that fell arrest

Without all bail shall carry me away,

My life hath in this line some interest,

Which for memorial still with thee shall stay.

When thou reviewest this, thou dost review

The very part was consecrate to thee:

The earth can have but earth, which is his due;

My spirit is thine, the better part of me:

So then thou hast but lost the dregs of life,

The prey of worms, my body being dead;

The coward conquest of a wretch’s knife,

Too base of thee to be remembered.

The worth of that is that which it contains,

And that is this, and this with thee remains.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 74 “But be contented: when that fell arrest”

Sonnet 74 “But be contented: when that fell arrest” continues with a further installment in this sub-sequence, which was begun in sonnet 73 “That time of year thou mayst in me behold”; it includes a focus on the aging and final death of the poet/speaker.

First Quatrain: Continuing the Thought

But be contented: when that fell arrest

Without all bail shall carry me away,

My life hath in this line some interest,

Which for memorial still with thee shall stay.

The speaker thus continues from the previous sonnet telling his audience to “be contented” even though they must be parted by the speaker’s death. The speaker emphasizes the inevitability of “that fell arrest” which will “carry [him] away.” He uses a legal metaphor saying there will be no “bail” to get him released from that arrest.

The speaker then opens the discussion to the possibility of a kind of immortality in which the body cannot participate but his greater self, the soul, can. And, of course, that immortality resides in the hands of his mighty talent which assists him in creating his little sonnet dramas.

The urgency of creating his bits of immortality continues to drive the speaker further into his adventure with art. Becoming aware of his considerable talent can never be enough; he knows he must engage that talent with all the strength he has. The speaker is convinced that his very soul depends on his ability to fulfill its destiny.

Second Quatrain: Part of the Planet

When thou reviewest this, thou dost review

The very part was consecrate to thee:

The earth can have but earth, which is his due;

My spirit is thine, the better part of me:

In the second quatrain, the speaker then avers that his body is simply a part of the earth, and the earth deserves to take it back. But he is more than earth; he is spirit and that cannot be taken from him, nor can it be taken from his loved ones.

This speaker’s love has been sculpted into his written creations, and he knows that they are issuing from his immortal soul. So even though his physical encasement must perish, he takes great comfort in knowing that he has left behind him great expressions of himself in his written works.

The speaker’s genuinely heartfelt desires continue to motivate him in his works. Even his dry spells will not allow him to rest; he pushes on despite all obstacles. Immortality becomes a shining star upon which he has precisely focused his attention.

This dedicated speaker knows that it takes honesty, sincerity, and perseverance applied along with his considerable talent to create the kinds of works that will outlive him and continue to honor his efforts.

Third Quatrain: The Base Body

So then thou hast but lost the dregs of life,

The prey of worms, my body being dead; The coward conquest of a wretch’s knife,

Too base of thee to be remembered.

The speaker then comforts his belovèds, among them his muse, that after the speaker has departed his body, those belovèds will have lost only the “dregs of life.” The physical body is nothing more than the “prey of worms.” Death has dominion over the physical body, and that dominion renders the physical encasement “too base” “to be remembered.”

Of the three bodies carried by each human being—causal, astral, and physical, sometimes narrowed down to merely spiritual and physical—this speaker has become cognizant that the physical body is the least of importance, while the other bodies are the ones that will remain attached to the soul until soul-liberation from them.

This notion harkens back to sonnet 72 (See “Shakespeare Sonnet 72 ‘O! lest the world should task you to recite’”at HubPages) as the speaker commanded that his name be buried with his body. He insists that loss of the gross body is not to be lamented.

This speaker retains the assurance that the mental and spiritual levels of being far outweigh in value that of the mere physical. While the physical body and the mental levels serve as instruments, it is the immortal, ever conscious, eternal soul that is responsible for the best part of him: his prowess in composition.

The Couplet: Soul in Art

The worth of that is that which it contains,

And that is this, and this with thee remains.

The couplet forcefully declares that the only value of the body is that it contains the soul. And this speaker has placed his soul into his art, which will continue to provide sustenance for all those other souls who may read his creations, including those family and friends who will mourn his loss.

The Premier World Poet: Knowledge Plus Talent

The remarkable knowledge that this speaker continues to reveal demonstrates why the writer of the Shakespeare canon has become known as the premier world poet. His skill is nearly flawless as he crafts his works with each word exactly in the place where it belongs.

Knowledge plus skill are the two necessary tools for all art. Without a balance and harmony of those two useful tools, a would-be poet becomes a mere poetaster. The Shakespeare writer demonstrates that balance and harmony in every poem and every play that he produces. His facility with language can teach anyone who wishes to accept its instruction.

Shakespeare Sonnet 75 “So are you to my thoughts as food to life”

Sonnet 75 “So are you to my thoughts as food to life” finds the speaker returning to contemplating his considerable talent as well as his belovèd muse who nourishes his inspiration in creating his sonnet dramas. But he also bemoans the dual nature of the thinking process.

Introduction and Text of Sonnet 75 “So are you to my thoughts as food to life”

In sonnet 75 “So are you to my thoughts as food to life” from the thematic group “The Muse Sonnets” in the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence, the speaker has been mourning the inevitable demise of his physical encasement and the possible waning of his talent. He was also broaching the same issue in sonnet 73 and sonnet 74.

In sonnet 75 “So are you to my thoughts as food to life,” the speaker returns to his favorite complex subject: his muse, his talent, and his ability to enshrine his deepest love in his sonnets as he battles the world of maya, whose dual nature always inserts negativity along with positivity.

The speaker notes that his muse comes and goes. At times he remains thoroughly nourished by his talent muse. But other times, he finds himself starving for inspiration. The writer is always hoping for continued inspiration for creativity.

However, this speaker also remains realistic as he bemoans the lack every time it occurs. He differs from other writers in that he is able to create fine dramas out of the very annoyance that is goading him.

Sonnet 75 “So are you to my thoughts as food to life”

So are you to my thoughts as food to life

Or as sweet-season’d showers are to the ground;

And for the peace of you I hold such strife

As ’twixt a miser and his wealth is found;

Now proud as an enjoyer, and anon

Doubting the filching age will steal his treasure;

Now counting best to be with you alone,

Then better’d that the world may see my pleasure:

Sometime, all full with feasting on your sight,

And by and by clean starved for a look;

Possessing or pursuing no delight,

Save what is had or must from you be took.

Thus do I pine and surfeit day by day,

Or gluttoning on all, or all away.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 75 “So are you to my thoughts as food to life”

The speaker is noting that the presence of his talent-muse waxes and wanes. Sometimes he can remain nourished by his considerable talent, while other times, he finds himself starving for inspiration during periods of dryness.

First Quatrain: Food of the Mind

So are you to my thoughts as food to life

Or as sweet-season’d showers are to the ground;

And for the peace of you I hold such strife

As ’twixt a miser and his wealth is found;

In the first quatrain, the speaker is addressing his muse as he avers that she nourishes his “thoughts” as “food” nourishes human “life.” Furthermore, this speaker’s muse enlivens him as the rain does the dry, parched earth. Such a useful analogy lends itself perfectly to the speaker’s purpose, which remains before him as a shining goal—he must continue to create his masterful little dramas.

The talented speaker says that he is so dependent on his muse that he must make a mighty effort to calm himself in the presence of this belovèd inspirer. He knows how profound his life has remained simply because of his considerable talent. He also has become aware of his great debt to the Giver of all talents.

If this speaker fails to engage productively with his God-given talent, he fears ultimate failure. The center of his life is his writing, his ability to produce significant, substantial art that will become and remain important to generations hence. The musing speaker likens his relationship with his muse to that of a “miser and his wealth.”

Thus the speaker is humbly deprecating himself to show that he knows he is not entirely responsible for his considerable gifts. However, despite those gifts, the speaker still has to strive to remain evenminded in his passion for creating.

He could become so flustered by doubt and fear of failure that he could disgrace himself. He, therefore, reminds himself from time to time that he must maintain his equilibrium. A too nearly perfect life would distill a dullness in this speaker; so while showing gratitude for his talent, he must also constantly strive to overcome his flaws.

On the one hand, he does comprehend that his life is hardly perfect, but on the other hand, he knows that his talent places his stature well above other artists. He must constantly strive for balance and harmony to produce the peace of mind allowing him to create.

Second Quatrain: The Art of Precision

Now proud as an enjoyer, and anon

Doubting the filching age will steal his treasure;

Now counting best to be with you alone,

Then better’d that the world may see my pleasure:

The speaker then avers that he is proud to be able to enjoy his ability to commune with his fecund muse, but he admits that he still suffers doubts that his ability will always remain as strong and vibrant as he is now experiencing.

The speaker’s humanness always demonstrates that he never becomes so self-important as to think he is more than a striving artist, despite the unique muse he has attracted. This speaker’s ability to remain humble while castigating himself for over-weaning pride actually infuses his art with precision.

The striving speaker badly needs to be precise in pursuing the qualities he most admires—truth, beauty, and love. Those three attributes have become a virtual holy trinity for this practicing artist-poet.

As an artist, this speaker remains steadfast in his zeal to portray those qualities in an honest but colorful array of works. Without doubt, he is thinking of his sonnets as he muses on such issues, but also there is no doubt that he includes in his thoughts his plays and other long poems.

Third Quatrain: Opposing States of Mind

Sometime, all full with feasting on your sight,

And by and by clean starved for a look;

Possessing or pursuing no delight,

Save what is had or must from you be took.

In the third quatrain, the speaker reports his opposing states of mind: sometimes he is able to “feast” on the muse’s bounty, and other times he is “starved” for the sight her. All artists experience such states. Creativity may seem to flow unfettered at certain unplanned times.

But then the dreaded dry periods arrive, and nothing seems to avail. During the dry periods, the artist feels that he has to strain for inspiration, that he has to try to take whatever he can get from the unyielding muse.

Interestingly, the muse of this speaker never remains absent for long, as he is able to create his fine little songs even in the face of a dry spell. He is so determined that he has become capable of creating colorful pieces that take for their subject his carping and complaining. Even as he is showing his contradictory nature, he is able provoke that muse into action, and that action always results in first rate work.

The Couplet: Two Mental Dramas

Thus do I pine and surfeit day by day,

Or gluttoning on all, or all away.

The speaker ends his musing on a plaintive note, saying that from day to day, he is tossed between those two states of mind: inspiration and lack thereof. The speaker remains at times like a glutton and at other times like a man starving.

The dualities of life are ever present, even for a divinely inspired artist whose talent is considerable. The artist who has become aware that life is composed of dualities will always have a leg up on those who have not entertained thoughts on the workings of that dual factuality of living.

The mayic world of delusion cannot hem round the deep thinking individual, and if an artist is not as deep thinking as he is creatively skillful, his talent will appear to remain meager despite the size and scope of his output.

Shakespeare Sonnet 76 “Why is my verse so barren of new pride”

The speaker in sonnet 76 “Why is my verse so barren of new pride”explores and dramatizes the fact that he always writes about one subject: his writing talent, which he calls his love.

Introduction and Text of Sonnet 76 “Why is my verse so barren of new pride”

This sonnet attests to the fact that the writer of the Shakespeare works has studied classical rhetoric. He uses the term “invention” which in classical rhetoric is the method for discovering a subject for composition. And he employs the term “argument” which means subject or content.

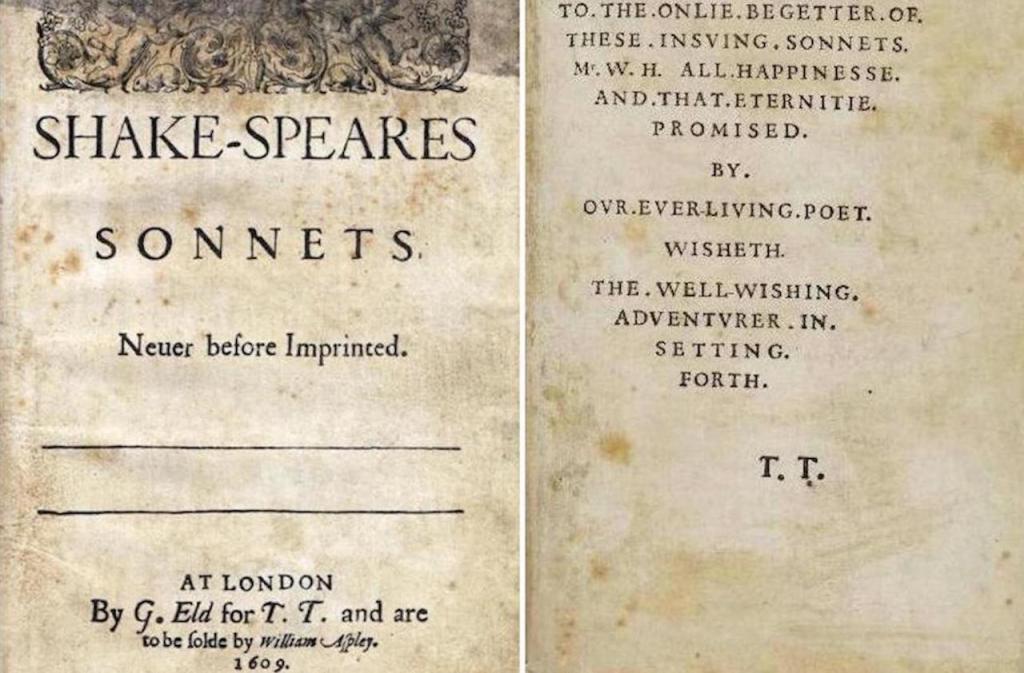

This knowledge possessed by the writer of these sonnets offers further evidence for the claim that the highly educated Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford was the actual writer of the works attributed to Gulielmus Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon—”William Shakespeare”— who attained little formal learning after leaving grammar school.

One misidentifying biographer has remarked, “It is amazing that William Shakespeare achieved so much after leaving school at the age of fourteen – with only seven years of formal education!” That would be “amazing” indeed, but the fact is that the man known as William Shakespeare is not likely the writer of the works attributed to him.

Recent research scholarship points increasing to the fact that the real “William Shakespeare” is Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, and the label “William Shakespeare” is the nom de plume employed by the earl.

Sonnet 76 “Why is my verse so barren of new pride”

Why is my verse so barren of new pride

So far from variation or quick change?

Why with the time do I not glance aside

To new-found methods and to compounds strange?

Why write I still all one, ever the same,

And keep invention in a noted weed,

That every word doth almost tell my name,

Showing their birth, and where they did proceed?

O! know, sweet love, I always write of you,

And you and love are still my argument;

So all my best is dressing old words new,

Spending again what is already spent:

For as the sun is daily new and old,

So is my love still telling what is told.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 76 “Why is my verse so barren of new pride”

The speaker in sonnet 76 “Why is my verse so barren of new pride” explores and dramatizes the fact that he always writes about one subject: his writing talent, which he calls his love.

First Quatrain: Posing Questions

Why is my verse so barren of new pride

So far from variation or quick change?

Why with the time do I not glance aside

To new-found methods and to compounds strange?

In the first quatrain, the speaker poses a compound questions: why do I fail to fill my sonnets with pride? and why do I continue to examine the same issues again and again? He wonders why his sonnets are always exploring the same subject and theme, without any variance of notice.

Then the speaker asks his second question: why do I continue to look straight a head instead of glancing about for novelty and depth? He then asks why he never seems to look anywhere for inspiration other than his accustomed place.

This speaker never explores any new manner of expression or any other “compounds strange,” or other subjects. The reader who has examined all of the sonnets from 1 through 75 can well understand these queries.

The speaker/writer has used only one form, the sonnet, and while the sonnets are traditionally sectioned into three subject areas by academics, a closer look can reveal that all, indeed, focus on the same general area: the poet’s talent and love of writing.

Second Quatrain: Continuing to Question

Why write I still all one, ever the same,

And keep invention in a noted weed,

That every word doth almost tell my name,

Showing their birth, and where they did proceed?

In the second quatrain, the speaker continues with another question, which essentially is a reiteration of the first two. He wonders why his writing is “ever the same.” He never departs from his theme and never attempts to “invent” new subjects matter to dress in a new fashioned way. This speaker “keep[s] invention in a noted weed”—the same subject dressed in the same clothing or sonnet form.

The speaker then says that, “every word doth almost tell my name.” This claim accurately reports that fact that an artist’s writing is as unique for identification as a fingerprint. The clever speaker avers that everything he writes demonstrates the same origin and the same progress.

Third Quatrain: Same Subject, Different Viewpoint

O! know, sweet love, I always write of you,

And you and love are still my argument;

So all my best is dressing old words new,

Spending again what is already spent:

Then the speaker addresses his “sweet love” and remarks, “I always write of you.” The speaker adds that, “you and love are still my argument.” He dramatically confesses that his one subject is all he cares about, and he spends his time “dressing old words new” and “[s]ending again what is already spent.” The speaker has no qualms about his seeming repetitiveness. He loves and understands his subject so well that he can present it from any number of viewpoints.

The Couplet: Like the Sun—Old and New

For as the sun is daily new and old,

So is my love still telling what is told.

The couplet likens the speaker’s “love” to the sun, which is always the same yet still “daily new.” The speaker tells “what is told” and by the retelling makes his love new. He reveals that his considerable talent has afforded him the process for experiencing new joy in perpetuity.

The speaker’s story, even as it seems to remain the same, becomes new through the speaker’s ingenuity and because of his intense, abiding love of his main subject. Thus, this speaker is engulfed in ever new joy, as he continues to create and re-create his little dramas filled with lovely images that represent his favorite love thoughts.

Shakespeare Sonnet 77 “Thy glass will show thee how thy beauties wear“

The speaker in sonnet 77 “Thy glass will show thee how thy beauties wear“is conversing with his poetself, reminding that self of the importance of his continued artistic endeavors.

Introduction and Text of Sonnet 77 “Thy glass will show thee how thybeauties wear”

In sonnet 77 “Thy glass will show thee how thy beauties wear”from the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence, the speaker is engaging the useful devices of a mirror and the empty pages of a book. He chooses those two objects in order to motivate himself to keep laboring intensely at his sonnet creation.

The speaker is expressing creatively his simple wish to complete a full dramatic record of his thoughts and feelings. He is endeavoring to create a dramatic memoir to serve as a reminder of his early perceptions of love and truth that he may peruse in his final years.

He insists that these mementos remain loyal to truth and reality so they may serve honestly as clear representations of his early perceptions of all that he deems good and beautiful.

Sonnet 77 “Thy glass will show thee how thy beauties wear”

Thy glass will show thee how thy beauties wear

Thy dial how thy precious minutes waste;

These vacant leaves thy mind’s imprint will bear,

And of this book this learning mayst thou taste.

The wrinkles which thy glass will truly show

Of mouthed graves will give thee memory;

Thou by thy dial’s shady stealth mayst know

Time’s thievish progress to eternity.

Look! what thy memory cannot contain,

Commit to these waste blanks, and thou shalt find

Those children nursed, deliver’d from thy brain,

To take a new acquaintance of thy mind.

These offices, so oft as thou wilt look,

Shall profit thee and much enrich thy book.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 77 “Thy glass will show thee how thy beauties wear”

The speaker is conversing with himself in this sonnet, which is an installment from “The Muse” thematic group of this sequence. He is musing intensely and profoundly in order to create a genuine “poetself,” a place where he can continue to remind his creative faculty of the importance of his work. He insists that he must continue crafting his fine poems—the ones that will result in his 154-sonnet sequence.

First Quatrain: The Poet’s Persona

Thy glass will show thee how thy beauties wear

Thy dial how thy precious minutes waste;

These vacant leaves thy mind’s imprint will bear,

And of this book this learning mayst thou taste.

The speaker admonishes his poet’s persona that three instruments will keep him informed about his progress:

- his mirror will remind him that he is aging;

- his clock will remind him that he is wasting time, and

- his book with only empty pages will persist in reminding him that he must continue to create and be productive in order to fill those blank pages with “learning.”

The creative speaker must continue to produce his sonnets so that he will be able to enjoy his creations into old age. He has affirmed his ability to create, but because of human inertia and habits of procrastination, he must continually remind himself of his goals. He has likely already wasted more time than he thinks can afford, but he knows he can persevere if he can muster the proper motivation.

The triple prompts of an aging face staring back from the mirror, the fleeting time measured by the clock, and empty pages that he needs to fill seem to be working to urge the speaker on to his creative efforts.

Second Quatrain: The Mirror and the Clock

The wrinkles which thy glass will truly show

Of mouthed graves will give thee memory;

Thou by thy dial’s shady stealth mayst know

Time’s thievish progress to eternity.

The speaker then again refers to the mirror and the clock. The mirror will “truly show” “the wrinkles” that will begin developing as the speaker ages, while the clock will keep ticking off the minutes as his life speeds by. But the mirror can be used as a motivational tool only if the speaker/poet will keep in mind the image of “mouthed graves.”

The open grave waits for the speaker who has ceased his work and can no longer create his valuable poems. The speaker creates such a gruesome image in order to offer himself motivation to spur his inner writer to greater effort that he may stop wasting his precious moments.

The speaker’s ability to urge himself on corresponds to his ability to fashion his creations. He has a talent for crafting beautiful, strong sonnets—a fact that has become clear to him. Now he must intensify his effort to fulfill that talent.

This effort requires a different skill but one that he knows is equally important. A skill unrealized remains as useless as a skill that never existed. He, therefore, engages every moment and all of his mental energy to make sure he realizes and engages his talent.

Third Quatrain: Command to Understand

Look! what thy memory cannot contain,

Commit to these waste blanks, and thou shalt find

Those children nursed, deliver’d from thy brain,

To take a new acquaintance of thy mind.

The speaker then shouts a command, “Look!” He commands his poetself to understand that he will not be able to remember all of the important and fascinating details of this life unless he fashions them into useful artifacts, that is, the sonnets, and “[c]ommits [them] to these waste blanks.”

The speaker insists that he must create his works because they are like his children, “deliver’d from [his] brain.” As the speaker/creator saves his “children” and fashions them into poems he will “take a new acquaintance,” and he will be reminded of his experiences in his old age.

The speaker appears to be grasping each moment, finding new ways to express ideas that extend universally to all artists. He has envisioned a world for his art, and he works to build that world with present metaphoric and mystical realities, in order that in his later years he can look back at his works and remember what he thought, how he felt, and even why he works so hard to create that world.

The Couplet: His Own Enrichment

These offices, so oft as thou wilt look,

Shall profit thee and much enrich thy book.

In the couplet, the speaker concludes his premise that if he makes haste and stays productive, he will be glad and “profit” much from “[his] book.” The speaker predicts that his enrichment will come from two sources: (1) the spiritual, which is the most important, and (2) the material, because he will also be able to gain monetarily from the sale of his book.

The speaker will “enrich” his memory, his heart and soul, as well as his pocketbook. The motivation must satisfy the speaker on all levels, if it is to work. He has noted many times in many sonnets that he is interested in capturing only beauty and truth.

The speaker knows that only what is true and beautiful will enhance his spirit as he looks back upon his life and his works. He also knows that this sequence of sonnets will have meaning and value for others also only if the poems contained therein are filled with truth and beauty, qualities with which others can identity.

The speaker also knows that folks will not appreciate the vulgar and the mundane as they look to experience through poetry the pure and exceptional. He remains aware that his exceptional talent has the ability to render him able to create a world that he and others will be capable of appreciating down through the centuries.

Shakespeare Sonnet 78 “So oft have I invok’d thee for my Muse”

The speaker in sonnet 78 “So oft have I invok’d thee for my Muse” addresses his muse with appreciation for her ever constant influence and power that elevates his art above lesser artists.

Introduction and Text of Sonnet 78: “So oft have I invok’d thee for my Muse”

The speaker in sonnet 78 “So oft have I invok’d thee for my Muse” from the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence compares his substantial muse to that of other artists. He reveals that most examples of the engagement of a muse remains for cosmetic purposes of style and outward appearance in the art.

This speaker, however, employs his superior muse for the purpose of creating content-rich, vital art filled with his favorite topics: love, beauty, and truth. Instead of merely constructing a beautiful, well-crafted sonnet form, this speaker is dedicated to establishing content of personal and universal substance.

This gifted, talent-rich speaker knows he is gifted and talented, he knows he can concoct sonnet forms, but more important for him is that he inform his art with vitally important words of truth.

Sonnet 78 “So oft have I invok’d thee for my Muse”

So oft have I invok’d thee for my Muse

And found such fair assistance in my verse

As every alien pen hath got my use

And under thee their poesy disperse.

Thine eyes, that taught the dumb on high to sing

And heavy ignorance aloft to fly,

Have added feathers to the learned’s wing

And given grace a double majesty.

Yet be most proud of that which I compile,

Whose influence is thine, and born of thee:

In others’ works thou dost but mend the style,

And arts with thy sweet graces graced be;

But thou art all my art, and dost advance

As high as learning my rude ignorance.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 78 “So oft have I invok’d thee for my Muse”

The speaker in sonnet 78 “So oft have I invok’d thee for my Muse” addresses his Muse with appreciation for her ever constant influence and power that elevates his art above lesser artists.

First Quatrain: Meshing of Theme and Subject

So oft have I invok’d thee for my Muse

And found such fair assistance in my verse

As every alien pen hath got my use

And under thee their poesy disperse.

In the first quatrain of sonnet 78, the speaker is addressing his subject, “love,” which he reveals that he has so often “invok’d for [his] Muse.” The sonnets all mesh together the theme and subject, concentrating on the speaker’s talent for poetry creation and his fascination for and interest in “love” and “truth.”

At times, the speaker addresses the poem itself and at other times he focuses on his subjects. Here he is addressing his favorite subject “love.” The speaker claims that “love” has provided him aid “in [his] verse.” Other subjects from time to time are attracted to his “alien pen,” but under the influence of love, which he takes as his Muse, he is able to bring forth his “poesy.”

Second Quatrain: The Singing of Angels

Thine eyes, that taught the dumb on high to sing

And heavy ignorance aloft to fly,

Have added feathers to the learned’s wing

And given grace a double majesty.

The speaker’s favorite subject is akin to the singing of angels; even more astoundingly, the eyes of love have “taught the dumb on high to sing.” The remarkable healing power of love even teaches “heavy ignorance” “to fly.” The “lofty” rarified air of love even “add[s] feathers to the learned’s wing.” Those who are already bright become brilliant through this all pervading, shining love.

This love furthermore “give[s] grace a double majesty.” These hyperbolic statements serve to underscore the exceptional quality of life that true, unconditional love offers as it effects and flourishes in the hands of a master craftsman the art of poetry.

Third Quatrain: Pride of Accomplishment

Yet be most proud of that which I compile,

Whose influence is thine, and born of thee:

In others’ works thou dost but mend the style,

And arts with thy sweet graces graced be;

The speaker then imparts to his Muse, his love, that she can be “proud” of what the speaker does in her favor; his Muse remains the “influence.” His inspiration has always come directly from the Muse.

The speaker’s Muse can experience pride in the knowledge of all the positive creations she has assisted him in creating. They will forever remain brilliant examples of the high quality of this Muse.

While comparing his inspiration from his Muse to that of other artists, this superior, talented speaker deems the others to lack substance. In other poets’ art, the Muse serves simply to correct “style,” and even though the Muse’s “grace” may be well represented, it lacks the substance of the accomplished craftsman.

The Couplet: Style and Substance

But thou art all my art, and dost advance

As high as learning my rude ignorance.

The speaker reveals the difference between mere style and substance. While other artists rely on the Muse for cosmetic purposes, this speaker says, “thou art all my art.” This gifted speaker’s art represents all aspects of the Muse’s power, and thus his art “do[th] advance / As high as learning my rude ignorance.” As usual, the speaker remains humble, giving credit to higher power, for he, as a poor servant, must always remain in certain “rude ignorance.”

Shakespeare Sonnet 79 “Whilst I alone did call upon thy aid”

While this Shakespearean speaker waits for what he believes to be true inspiration, he goes ahead and writes whatever he can to keep his creative juices flowing. The speaker of sonnet 79 addresses his muse directly, sorting out once again his own contribution from that of the muse.

Introduction and Text of Sonnet 79 “Whilst I alone did call upon thy aid”

The speaker in the “Muse Sonnets” sequence from the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence has repeatedly demonstrated his deep obsession with poetry creation. It is, indeed, ironic that he finds he can write even about complaining about not being able to write. This kind of devotion and determination finds expression over and over again.

While this speaker waits for what he believes to be true inspiration, he goes ahead and writes whatever he can to keep his creative juices flowing. The speaker of sonnet 79 “Whilst I alone did call upon thy aid” is addressing his muse directly, attempting to sort out once again his own individual offerings from that of the muse’s contributions.

Sonnet 79 “Whilst I alone did call upon thy aid”

Whilst I alone did call upon thy aid

My verse alone had all thy gentle grace;

But now my gracious numbers are decay’d,

And my sick muse doth give an other place.

I grant, sweet love, thy lovely argument

Deserves the travail of a worthier pen;

Yet what of thee thy poet doth invent

He robs thee of, and pays it thee again.

He lends thee virtue, and he stole that word

From thy behaviour; beauty doth he give,

And found it in thy cheek; he can afford

No praise to thee but what in thee doth live.

Then thank him not for that which he doth say,

Since what he owes thee thou thyself dost pay.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on “Whilst I alone did call upon thy aid”

The speaker of sonnet 79 “Whilst I alone did call upon thy aid” is once again directly facing his muse, as he attempts to sort out his own contribution from the inspirational contribution of the muse. Making such fine distinctions helps generate drama as well as useful images with which to create his sonnets.

First Quatrain: Bereft of the Muse

Whilst I alone did call upon thy aid

My verse alone had all thy gentle grace;

But now my gracious numbers are decay’d,

And my sick muse doth give an other place.

In the first quatrain of sonnet 79, the speaker declares that when he has depended solely on his muse for writing his sonnets, the poems professed the “gentle grace” that belongs to that muse.

But the speaker now finds himself bereft of his muse, that is, another one of those pesky periods of low inspiration is assailing him. His “sick muse” is letting him down, and he is failing to accumulate the number of sonnets he wishes to produce.

Writers have to write, and when they are faced with a blank page that seems to want to remain silent, they must cajole and pester their thought processes in order to find some prompt that will motivate the images, ideas, and context to produce the desired texts.

This speaker faces his muse—which is his own soul/mental awareness—and demands results. His determination always results in product; thus he has learned never to stay silent for long. His clever talents seem to be always equal to the task of creativity.

Second Quatrain: Search for a Better Argument

I grant, sweet love, thy lovely argument

Deserves the travail of a worthier pen;

Yet what of thee thy poet doth invent

He robs thee of, and pays it thee again.

The speaker, who is an obsessed poet, admits that “sweet love” deserves a better “argument” than he is presently capable of providing. He knows that such work demands “a worthier pen,” but when the speaker finds himself in such a dry state, destitute of creative juices, he simply has to ransack his earlier work to “pay[ ] it thee again.”

To be able to offer at least some token, the speaker has to “rob” what the muse had earlier given him. The act does not make him happy, but he feels that he must do something other than whine and mope.

Making his own works new again, however, results in a freshness that will work time and time again, but only if it can pass the poet’s own smell test. He will not allow warmed over, obviously stale images to infect his creations.

Third Quatrain: Crediting the Muse

He lends thee virtue, and he stole that word

From thy behaviour; beauty doth he give,

And found it in thy cheek; he can afford

No praise to thee but what in thee doth live.

Even such a thieving poet “lends thee virtue.” The speaker metaphorically likens his reliance on the muse to the crime of theft, but he makes it clear that he gives the muse all of the credit for his ability even to steal. It is the music unity of “behaviour” and “beauty” that lend this speaker his talents.

The speaker says he cannot accept praise for any of the works, because they all come from the muse: they are “what in thee doth live.” His talent and his inspiration that find happy expression in his works he always attributes to his muse. On those occasions that the speaker becomes too full of himself, he pulls back humbly, even though he knows he has let the cat out of the bag.

The Couplet: Undeserving of Music Gratitude

Then thank him not for that which he doth say,

Since what he owes thee thou thyself dost pay.

Finally, the speaker avers that he is not deserving of any gratitude or even consideration by the muse. He insists, “what he owes thee thou thyself dost pay.” All that the speaker may owe his muse is already contained in that muse, including any gratitude he may want to express.

Such a description of his “muse” indicates that the speaker knows the muse is none other than his own Divine Creator. His humble nature allows him to construct his sonnets as prayers, which he can offer to his Divine Belovèd.

The distinction between Creator and creation remains a nebulous one. There always seems to be a difference without an actual difference—or perhaps a distinction without a difference. What is united cannot be divided unless the human mind divides them.

The writer, especially the creative writer, has to understand, appreciate, and then be able to manipulate the Creator/creation unity if he is to continue creating. This Shakespearean speaker understands that relationship better than most writers who have even written; that understanding is responsible for the durability and classic status of the Shakespeare canon.

Shakespeare Sonnet 80 “O! how I faint when I of you do write”

The speaker in sonnet 80 “O! how I faint when I of you do write” is once again examining the nature of his most important subject, love, in regard to his talent, as he recognizes the intervention of not only the muse, but also the Divine Muse or Spirit-God.

Introduction and Text of Sonnet 80 “O! how I faint when I of you do write”

In sonnet 80 from the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence, the speaker is addressing God (or the Divine Muse), although he never uses any term to indicate so, except for the word “spirit” in the first quatrain, which is here referring to the individual soul. The speaker uses the same technique that he has employed before: he segments his “self ” into parts in order to praise while still remaining humble.

The speaker is undoubtedly aware of the concept of the religious trinity which explains the nature of the Divine Creator’s Ultimate Reality as tripartite: the force outside of nature, the force informing nature, and the force inside of nature. The Hindus refer to this force as Sat-Tat-Aum, and the tradition of the Judeo-Christian religion refers to it as “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.”

Sonnet 80 “O! how I faint when I of you do write”

O! How I faint when I of you do write

Knowing a better spirit doth use your name,

And in the praise thereof spends all his might,

To make me tongue-tied, speaking of your fame!

But since your worth—wide as the ocean is,—

The humble as the proudest sail doth bear,

My saucy bark, inferior far to his,

On your broad main doth wilfully appear.

Your shallowest help will hold me up afloat,

Whilst he upon your soundless deep doth ride;

Or, being wrack’d, I am a worthless boat,

He of tall building and of goodly pride:

Then if he thrive and I be cast away,

The worst was this;—my love was my decay.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 80 “O! how I faint when I of you do write”

This speaker is reminding his inner self of the most important aspects of his God-given talent. He knows the importance of maintaining a level of humbleness that will allow him to continue to perfect and keep his works genuine and guileless.

First Quatrain: A Humble Weakness

O! How I faint when I of you do write

Knowing a better spirit doth use your name,

And in the praise thereof spends all his might,

To make me tongue-tied, speaking of your fame!

In the first quatrain, the speaker exclaims,”O! How I faint when I of you do write.” He is overcome with a weakness that keeps him humble. This speaker is essentially dividing his consciousness into two parts, referring to one as “I” and the other as “he.” The “better spirit” refers to the muse or his native talent; he separates his various “selves” in order to explore them.

The entity becomes tripartite, representing the physical, mental, and spiritual levels of being that all unite to produce fine art. The speaker’s self qua self becomes “tongue-tied” when “speaking of the fame” of the Over-Soul’s Divinity.

He spends “all of his might” praising the Divine, and thus he transforms into a humble servant as he compares his lesser talents to those of God, or the Over-Soul or Super Muse.

Second Quatrain: Litotes of Reason

But since your worth—wide as the ocean is,—

The humble as the proudest sail doth bear,

My saucy bark, inferior far to his,

On your broad main doth wilfully appear.

The speaker then avers that the value of the Divine is “wide as the ocean,” clearly an understatement (litotes of classical rhetoric), yet suitable for his purposes. The humble speaker then metaphorically likens himself to a small boat which competes with a much larger vessel.

The speaker asserts that the Divine includes and recognizes all from the humblest to the “proudest.” His own small boat, which he labels a “saucy bark” and claims its inferiority, still finds favor enough to “appear” with the “proudest” on this all-encompassing sea. This sea, of course, metaphorically represents the art world and by extension the entire cosmos.

Third Quatrain: Muse Inspired Grace

Your shallowest help will hold me up afloat,

Whilst he upon your soundless deep doth ride;

Or, being wrack’d, I am a worthless boat,

He of tall building and of goodly pride:

Addressing the Divine, the speaker avers that even the smallest aid offered by His Greatness “will hold me up afloat.” This upliftment happens simultaneously with his other self “rid[ing]” “upon your soundless deep.”

While the muse remains silent, the speaker is permitted voice by the same grace that creates the muse and his own creative self. The talented speaker thus demonstrates the unity of the muse and his own creative self, even as he has separated them, merely for the purpose of examining them.

Again, the speaker displays his humility by claiming, “I am a worthless boat,” and at the same time averring, “He (his “self” that functions as the muse) appears “of tall building and of goodly pride.” This convenient splitting allows the speaker to remain humble yet retain his pride.

The Couplet: A Triumvirate of Self

Then if he thrive and I be cast away,

The worst was this;—my love was my decay.

The couplet binds the tripartite self together again with the speaker’s usual and most important subject—”love.” If the writing self, who is the most ordinary self, fails while his muse succeeds, then the ordinary self gets the better part of it all because he has remained true to his love, and they continue united as they venture forth aging together.

The speaker may at times find himself leaning in a direction that he does not find helpful. As he becomes too proud of his own abilities, he knows that he must temper that pride in order to remain open to possibilities for his creations. He depends on the Great Muse—or God—and he continues to remind himself that his accomplishments remain dependent on his Creator.

Although this speaker never becomes overly solicitous through his prayers, he nevertheless offers the kinds of prayers that are indistinguishable from clarified dramatic performances.

He uses his talent to praise his Creator in ways that remain unique to his own individual talent. He knows well that he must remain humble, and as he continues to pursue his art, he also continues to pursue his path through life that leads to better, more informed art.

This talented, sincere speaker has long eschewed the fake and paltry puffery in favor of genuine works that will become classic as they portray what is real and lasting for each human heart and mind.

Shakespeare Sonnet 81 “Or I shall live your epitaph to make”

Sonnet 81 “Or I shall live your epitaph to make” offers a glowing tribute to the speaker’s poems. He often extols the virtue of his own poetry because he is certain it will live long after he is gone.

Introduction and Text of Sonnet 81 “Or I shall live your epitaph to make”

In sonnet 81 “Or I shall live your epitaph to make” from the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence, the speaker addresses his poem, as he often does. In this sonnet, the speaker is celebrating his gifts and offering a magnificent, glowing tribute to the poems themselves.

This speaker has often extolled the virtue of his own poetry because he is certain his creative compositions will live long after he has shuffled off the mortal coil. Now the speaker chooses to place the poems themselves, indeed, he even gives a nod to his plays, in the spotlight and shower on them the immortality that the feels they will experience.

Sonnet 81 “Or I shall live your epitaph to make”

Or I shall live your epitaph to make

Or you survive when I in earth am rotten;

From hence your memory death cannot take,

Although in me each part will be forgotten.

Your name from hence immortal life shall have,

Though I, once gone, to all the world must die:

The earth can yield me but a common grave,

When you entombed in men’s eyes shall lie.

Your monument shall be my gentle verse,

Which eyes not yet created shall o’er-read;

And tongues to be your being shall rehearse,

When all the breathers of this world are dead;

You still shall live,—such virtue hath my pen,—

Where breath most breathes,—even in the mouths of men.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Shakespeare Sonnet 81 “Or I shall live your epitaph to make”

Sonnet 81 “Or I shall live your epitaph to make” offers a glowing tribute to the speaker’s poems. He often extols the virtue of his own poetry because he is certain it will live long after he left the world.

First Quatrain: Posing Two Ideas

Or I shall live your epitaph to make

Or you survive when I in earth am rotten;

From hence your memory death cannot take,

Although in me each part will be forgotten.

In the first quatrain, the speaker proposes two ideas: he will live to write the epitaph for his poetry, or his poetry will outlive him. The speaker chooses to believe and act on the latter because “From hence your memory death cannot take.”

Even though the speaker, who lives in a physical body, must eventually die, death cannot take away his sonnets once he has written them. While the writer of the sonnets will be forgotten, the works themselves will remain eternally.

Second Quatrain: Naming His Art

Your name from hence immortal life shall have,

Though I, once gone, to all the world must die:

The earth can yield me but a common grave,

When you entombed in men’s eyes shall lie.

After having finished composition of each sonnet, the speaker christens the work, giving it a name, and he confidently proclaims “your name from hence immortal life shall have.” This speaker has often shown his confidence in his talent, and he has often demonstrated his heavy reliance on his poetic muse.

The speaker then remarks that while his earthly flesh must be buried in that earth, his sublime poetry will live “in men’s eyes.” The interesting metaphor of likening the poetry to the entombed body generates the opposite reality. The poetry is not “entombed” but is full of vibrant life.

Third Quatrain: Poetic Monument

Your monument shall be my gentle verse,

Which eyes not yet created shall o’er-read;

And tongues to be your being shall rehearse,

When all the breathers of this world are dead;

The poetry will be a monument to the poet, but more importantly, it will be a monument to itself. The speaker calls his poetry “gentle verse.” And the speaker then indicates that it is being written for “eyes not yet created.” The speaker often projects his thoughts far into the future.

Not only will eyes play lovingly over this speaker’s “gentle verse,” but also “tongues to be your being shall rehearse.” The speaker seems to be referring not only to his sonnets but also to his plays, which, of course, continue even today to be performed world-wide.

The Couplet: Art Outliving Artist

You still shall live,—such virtue hath my pen,—

Where breath most breathes,—even in the mouths of men.

The speaker dramatizes the future of his poems in the couplet. When all the people who are living at the time of the speaker have vanished, he is confident that his poetic works “still shall live.” It is by “virtue” of his “pen” that such a phenomenon can occur. He believes the poems as they will be spoken and read by future generations will have even more life than he could ever envision.

Shakespeare Sonnet 82 “I grant thou wert not married to my Muse”

In sonnet 82 “I grant thou wert not married to my Muse,” the speaker is addressing his favorite subject, which is “love,” as he dramatizes the superior nature that this subject offers to his art.

Introduction and Text of Sonnet 82 “I grant thou wert not married to my Muse”

Sonnet 82 “I grant thou wert not married to my Muse” from the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence finds the speaker doing what he does best: dramatizing the nature of his favorite subject and how it infuses his own craft with the delicious qualities of truth and beauty.

This speaker continues to demonstrate his love for his own talent, his Muse, and creations. He especially holds originality in high regard. His God-given (Muse-driven) talent affords him the ability to detect and distinguished the genuine from the fake in art.

Sonnet 82 “I grant thou wert not married to my Muse”

I grant thou wert not married to my Muse

And therefore mayst without attaint o’erlook

The dedicated words which writers use

Of their fair subject, blessing every book.

Thou art as fair in knowledge as in hue,

Finding thy worth a limit past my praise;

And therefore art enforc’d to seek anew

Some fresher stamp of the time-bettering days.

And do so, love; yet when they have devis’d

What strained touches rhetoric can lend,

Thou truly fair wert truly sympathized

In true plain words by thy true-telling friend;

And their gross painting might be better used

Where cheeks need blood; in thee it is abus’d.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 82 “I grant thou wert not married to my Muse”

In Sonnet 82 “I grant thou wert not married to my Muse,” this speaker is demonstrating his love for his own talent, his Muse, and creations. He especially holds originality in high regard.

First Quatrain: Distinction between Muse and Love

I grant thou wert not married to my Muse

And therefore mayst without attaint o’erlook

The dedicated words which writers use

Of their fair subject, blessing every book.

In the first quatrain of sonnet 82, the speaker is again addressing his favorite subject “love.” And he is telling love that he knows his favorite subject and his “Muse” are not the same or even closely linked as by marriage. Because the Muse does not align herself irrevocable with any particular subject, theme, or topic, the writer’s inspiration and subject matter do not taint each other.

If the writer praises one, he is not necessarily praising the other. Writers will always be “blessing every book.” But their subject and their Muse are not always equal in their production and therefore cannot partake of equal appreciation.

The writer alone decides to whom he will offer his gratitude for any particular piece of work. The speaker is affirming his autonomy, even as he grants that his Muse remains vital in his quest to create useful dramas.

Second Quatrain: The Beauty of Love

Thou art as fair in knowledge as in hue,

Finding thy worth a limit past my praise;

And therefore art enforc’d to seek anew

Some fresher stamp of the time-bettering days.

The speaker then alerts love that it is “as fair in knowledge as in hue.” He is asserting that the beauty of love lies not only in its outward expression but also primarily in its knowledge. Love’s value exceeds the ability of the speaker to praise it. The writer who falls in love with love will seek answers to earthly questions as he seeks, “Some fresher stamp of the time-bettering days.”

The original writer will not be satisfied by merely copying others but will be motivated by the ever-new inspiration that love continuously infuses into his vision. Such a writer does not wait for the Muse, and readers will have noted this trait in this speaker’s method.

He writes even when he feels he has nothing to write about except to complain that he cannot write. Such depth and strength of talent seldom ever fail to assist him in producing his colorful pieces.

Third Quatrain: Straining Rhetoric

And do so, love; yet when they have devis’d

What strained touches rhetoric can lend,

Thou truly fair wert truly sympathized

In true plain words by thy true-telling friend;

Love works in a similar fashion. Even as those who formulated the rules of rhetoric have warned against the “strained touches” that the art of rhetoric can offer, love still remains true.

The speaker then drives his claim home by using the rhetorical device called repetition in the line, “Thou truly fair wert truly sympathized / In true plain words by thy true-telling friend.”

This highly educated and perceptive speaker employs the term “truly” twice and its root “true” twice in the two lines. Through this rhetorical device of repetition, he is emphasizing his stance that “love” and “truth” are, in fact, married, or unified for him.

The Couplet: Poetry and Painting

And their gross painting might be better used

Where cheeks need blood; in thee it is abus’d.

In the couplet, the speaker compares his sonnet to a painting, which has to use gross physical forms, where the painter must put blood in the cheek of his subject. But such grossness is not required for the written word.

And this speaker avers that in the sonnet “it is abus’d.” Too physical a subject abuses the spirituality with which the subjects “love” and “truth” endow his art. Thus the speaker has again touted his own talent, while praising and showing gratitude for his Muse.

Shakespeare Sonnet 83 “I never saw that you did painting need”

The speaker in sonnet 83 “I never saw that you did painting need” again offers a tribute to his poetry, as he dramatizes the nature of poetry cosmetics pitted against profound insight and inspiration.

Introduction and Text of Sonnet 83 “I never saw that you did painting need”

In sonnet 83 “I never saw that you did painting need” from the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence, this gifted speaker asserts his desire to remain a humble servant of truth. His desire to offer only beauty that bespeaks sincere love will guide him to create honest art.

This speaker is aware that many artists turn to flattering language to fill their poems with tinsel and tinker. This speaker/poet dramatizes the nature of a humble heart that is aware of its gifts, but he remains insistent that he will use his considerable gifts to create only works that represent truth and beauty. His art is his love, as he has many times proclaimed.

This speaker seems to be taking a vow or making a pact with his readers that his works will always strive to represent only the most profound subjects. He will reveal his subjects in their own brilliant light and not add glitter to falsely enhance them.

This poet-speaker knows that he possesses the ability to accomplish all of his worthy goals for his writing because he knows how deeply he loves his art as well as the qualities of divine love, truth, and beauty that he seeks for living his life.

Sonnet 83 “I never saw that you did painting need”

I never saw that you did painting need

And therefore to your fair no painting set;

I found, or thought I found, you did exceed

That barren tender of a poet’s debt:

And therefore have I slept in your report,

That you yourself, being extant, well might show

How far a modern quill doth come too short,

Speaking of worth, what worth in you doth grow.

This silence for my sin you did impute,

Which shall be most my glory, being dumb;

For I impair not beauty being mute,

When others would give life, and bring a tomb.

There lives more life in one of your fair eyes

Than both your poets can in praise devise.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 83 “I never saw that you did painting need”

The speaker in sonnet 83 is offering a heartfelt tribute to his own poetry. Also, he is revealing and dramatizing the harm that mere cosmetics smeared over simplistic, artificial fakery causes, as such harm damages and prevents profundity from taking center stage.

First Quatrain: No Mere Cosmetics

I never saw that you did painting need

And therefore to your fair no painting set;

I found, or thought I found, you did exceed

That barren tender of a poet’s debt:

Once again, addressing his poetry, the speaker-poet avers that he has never engaged in mere cosmetic dressing for his poems. He has always believed that his subjects of love, beauty, and truth provide the profundity that his creations need.

This speaker believes that he, as a poet, owes a debt to his audience, and this speaker vows that he will always pay that debt. Unlike many superficial poets, this poet-speaker will not condescend to use poetic devices such as metaphor, simile, and image for mere window dressing.

His work will always reflect his dedication to heartfelt art produced by a genuinely workable method. It is because of this dedication to his art that he bitterly complains from time to time about his periods of dryness—times when he feels abandoned by his muse.

Although his basic premise may be based upon a complaint, he still manages to create a unique little drama that not only reveals his issue but always at the same time also demonstrates the profound nature of his suffering.

Second Quatrain: The Shallow “Moderns”

And therefore have I slept in your report,

That you yourself, being extant, well might show

How far a modern quill doth come too short,

Speaking of worth, what worth in you doth grow.

Every time period has its genuinely talented artists as well as its less talented and even its poetasters and other fakes or pretenders. Even as the contemporaries of the genuine artists fall into the genuine vs the fraudulent categories, the “modern” way always brings with it those shallow writers who depend upon disingenuousness and cosmetic touches to make their poetry appear original, even as it merely shows pretension and conformity.

Such a situation can be seen in poets who become critics in order to make a case for their own poetry. A present-day example of this debauchery presents itself in the highly overrated poet and essayist, Robert Bly, who has fabricated the idea of “picturism” to support his false definition of imagism.

Such artists behave like adolescents, who must change their style out of an ignorant rebellion and an immature attempt to belong to something they do not completely understand. Instead of studying the nature of love, beauty, spirituality, and truth, they are content to dabble in “worth[less]” pursuits that lead to counterfeit art.

Third Quatrain: Base Instincts

This silence for my sin you did impute,

Which shall be most my glory, being dumb;

For I impair not beauty being mute,

When others would give life, and bring a tomb.

The poem may seem to impart “silence for my sin,” but for those speakers, who limit their intentions to base instincts, this speaker understands that they “impair not beauty being mute.”

This sincere speaker’s own poems will sing with “life,” while the superficial will “bring a tomb.” The speaker’s passion for life will live in his works because he has struggled to maintain his integrity, while paying homage to his own considerable talents.

The repetition of his subjects will not be taken as “dumb” but will “be most my glory.” While this speaker may run the risk of sounding as if he were dabbling in mere braggadocio, he knows his genuine feelings will allow him to escape such a charge. He also knows the depth and breadth of his own talent for drama creating, and he is convinced that his artistic bravado will remain strong as well as accurate and genuine.

The Couplet: Poetry of the Profound

There lives more life in one of your fair eyes

Than both your poets can in praise devise.

The speaker declares that his own poetry, because of the profound history, philosophy, and spirituality he has struggled to place into it, will contain “more life” than that of any two less honest poets.

The speaker takes such honor for himself only in that he has been able to assist his own poems into creation. This speaker’s humility can be achieved by the very talent that could, in a less realized poet, give rise to a presumptuous pride.

The overzealous fakes will always out themselves through their inability to remain consistent, as well as their through their vain attempts to make the vulgar and profane sound profound and sacred.

Readers who appreciate fine art will always be able to distinguish between the genuine and the bogus. This speaker maintains confidence in both his own ability to write and the ability of his readers to read, understand, and appreciate the depth and value of his works.

Shakespeare Sonnet 84 “Who is it that says most? which can say more”

The speaker in Shakespeare Sonnet 84 “Who is it that says most? which can say more”is examining the true ground of art, which is the human soul. He avers that the truth of the soul is indispensable for artists who aspire to be genuine.

Introduction and Text of Sonnet 84 “Who is it that says most? which can say more”

The speaker in sonnet 84 “Who is it that says most? which can say more” is once again exploring the nature of the genuine vs fake art. He contends that each human soul’s abundance of truth provides the repository from which all artists may partake in producing their works.

This speaker believes that only genuine feeling can produce useful, effective, beautiful art. His interest in pursuing the reality of truth and beauty continue to motivate his poetics and its exploration.

Sonnet 84 “Who is it that says most? which can say more”

Who is it that says most? which can say more

Than this rich praise,—that you alone are you?

In whose confine immured is the store

Which should example where your equal grew.

Lean penury within that pen doth dwell

That to his subject lends not some small glory;

But he that writes of you, if he can tell

That you are you, so dignifies his story,

Let him but copy what in you is writ,

Not making worse what nature made so clear,

And such a counterpart shall fame his wit,

Making his style admired every where.

You to your beauteous blessings add a curse,

Being fond on praise, which makes your praises worse.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 84 “Who is it that says most? which can say more”

The speaker examines the true ground of art, which is the human soul. He contends that the truth of the soul is indispensable for artists who aspire to be genuine.

First Quatrain: A Two Pronged Question

Who is it that says most? which can say more

Than this rich praise,—that you alone are you?

In whose confine immured is the store

Which should example where your equal grew.

In the first quatrain of sonnet 84, the speaker begins with a two-part question: Who is capable of producing the brightest discourse? and who can produces more than that produced by the genuine?

The speaker is addressing his soul, the life force that makes each human being unique, as he has many times before, and with his rhetorical question asserts that the greatest praise one can receive is the recognition of one’s uniqueness.

The speaker then insists that each individual contains the seeds for his own growth. His art production will “equal” the value of the individual’s worth because each person is unique. The speaker, of course, is examining his own uniqueness specifically, but his claims also flourish to universality through his broad scope and study.

Second Quatrain: A Poor Writer

Lean penury within that pen doth dwell

That to his subject lends not some small glory;

But he that writes of you, if he can tell

That you are you, so dignifies his story,

The speaker then asserts that the writer who cannot afford “some small glory” to his own soul is, indeed, a poor writer. The reader has become well aware that the speaker’s obsession with the art of writing dominates his musings. This talented speaker has intuitively grasped that the soul is the true creator, being a spark of the Supreme Creator.

Therefore, the speaker can say with certainty that if the writer will contact his soul, he will find that his work “dignifies his story.” The speaker, however, does also insist that the writer must be able to distinguish the soul from the ego; the writer must be able to “tell / That you are you.”

Third Quatrain: From the Soul

Let him but copy what in you is writ,

Not making worse what nature made so clear,

And such a counterpart shall fame his wit,

Making his style admired every where.

The speaker claims that all the writer has to do is “copy what in [the soul] is writ.” The soul is the repository of all knowledge, and if the writer will contact the soul, he will never be guilty of “making worse what nature made so clear.” And furthermore, that soul-writer’s style will be “admired every where.”

The speaker, as the reader has discovered in many of the sonnets, is most interested in truth, beauty, and love. And as such a genuine of the true and beautiful, this speaker continues to castigate poetasters for their betrayal of truth.

This speaker also has on many occasions rebuked pretenders who use poetic devices as mere cosmetics. This speaker holds special scorn for those who abuse love. In this sonnet, the speaker is especially concerned with truth; he insists that soul knowledge is the answer to the opening question.

The Couplet: Ego Failure

You to your beauteous blessings add a curse,

Being fond on praise, which makes your praises worse.

In the couplet, the speaker scolds the ego, who, when it fails to attend the soul, “add[s] a curse” to its own “beauteous blessings.” And when the ego allows itself to become inebriated “on praise,” the resulting art becomes inferior. If such art is praised, it is done so by sycophants, not true art lovers.

Shakespeare Sonnet 85 “My tongue-tied Muse in manners holds her still“

The speaker of all the Shakespeare sonnets has honed a skill in praising his own talent while appearing to remain humble.

Introduction and Text of Sonnet 85 “My tongue-tied Muse in manners holds her still”

In sonnet 85 “My tongue-tied Muse in manners holds her still” from the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence, the speaker virtually lauds his own poems while humbly attributing their worth to the muse, who remains visibly humble.

This speaker has devised many little dramas in which he has shown that his humility can remain intact while at the same time demonstrate that he knows his work is outstanding. The speaker can assert his worth while at the same time dramatize his inner humbleness that remains clothed in gratitude.

The speaker often pries apart his trinity of theme—truth, beauty, love—in order to explore each quality in depth. He does the same with the trinity of art—artist, making, art—in order to examine and craft his little dramas.

As he often speaks to his poems, he is able to demonstrate the strength and beauty that each one possesses. He can do all this without appearing to be boastful: he is merely demonstrating what truly exists—not what he might wish to fabricate or obfuscate into existence, as do poetasters such as Robert Bly.

Sonnet 85 “My tongue-tied Muse in manners holds her still”

My tongue-tied Muse in manners holds her still

Whilst comments of your praise, richly compil’d,

Deserve their character with golden quill,

And precious phrase by all the Muses fil’d.

I think good thoughts, whilst others write good words,

And, like unletter’d clerk, still cry ‘Amen’

To every hymn that able spirit affords,

In polish’d form of well-refined pen.

Hearing you prais’d, I say ‘’Tis so, ’tis true,’

And to the most of praise add something more;

But that is in my thought, whose love to you,

Though words come hindmost, holds his rank before.

Then others for the breath of words respect,

Me for my dumb thoughts, speaking in effect.

Original Text

Better Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 85 “My tongue-tied Muse in manners holds her still”

While appearing to remain humble, the clever speaker of all the Shakespeare sonnets has honed a skill in praising his own talent, as she explores that nature of art, talent, and art creation.

First Quatrain: The Quiet Composer

My tongue-tied Muse in manners holds her still

Whilst comments of your praise, richly compil’d,

Deserve their character with golden quill,

And precious phrase by all the Muses fil’d.

The speaker is addressing his sonnet, telling it that its creator remains quiet when others praise it, but he freely admits that the sonnet deserves the “praise, richly compil’d.” The sonnet shines as though written with a pen of golden ink. Not only the Muse of poetry, but also all of the other Muses are filled with pleasure at the valuable sonnets that the speaker has created.

This speaker claims that his Muse is “tongue-tied,” but the sonnet, as usual, demonstrates otherwise. The speaker never allows himself to be tongue-tied, and at times, when he might be struggling to find expression, he merely blames the Muse until he once again takes command of his thoughts, compressing them into his golden sonnets.

Second Quatrain: The Rôle of Critics

I think good thoughts, whilst others write good words,

And, like unletter’d clerk, still cry ‘Amen’

To every hymn that able spirit affords,

In polish’d form of well-refined pen.

While the speaker admits that he “think[s] good thoughts,” it is the critics who “write good words” about his sonnets. This talented speaker cannot take credit for their brilliance in exposing what a gifted writer he is. And thus, while he certainly agrees with those “good words,” he can blush outwardly while inwardly “cry[ing] ‘Amen’.”

The speaker now is emphasizing the force of his soul on his creative power as he refers to his poem as a “hymn.” To each of his sonnets, he will owe his fame, any praise they may garner him, and also the recognition he will receive for having composed them.

The speaker remains eternally in deep agreement with his words: “In polish’d form of well-refined pen.” As the speaker distinguishes his ego from the sonnet itself and also his process in creating them, he will be able to attain a humbleness while at the same time completely agree that he, in fact, will always merit the praise his creations bring him.

Third Quatrain: Fond of Praise

Hearing you prais’d, I say ‘’Tis so, ’tis true,’

And to the most of praise add something more;

But that is in my thought, whose love to you,

Though words come hindmost, holds his rank before.

The speaker then tells his sonnet that when he hears it praised, he says, “’Tis so, ’tis true.” But then the speaker also has something further to express regarding that praise; he would have to add some deprecating thought in order not to come off as engaging in braggadocio.

Because the speaker’s foremost thought is always the love he puts into his sonnets, whatever his casual remarks tend to be, he knows that those remarks are much less important than those written into the sonnet. The sonnet represents the speaker’s soul force, not the conversational small talk that results from responding to those who praise his work.

The Couplet: True Speaking

Then others for the breath of words respect,

Me for my dumb thoughts, speaking in effect.

While others praise his sonnets for their clever craft with words, the speaker feels that his thoughts, which remain unspoken but yet exist as the sonnet, are the ones that do the true speaking for him. Thus he holds that whatever he crafts will remain closer to truth than what anyone—critic, scholar, or admirer—could ever add to his conveyed message.

Shakespeare Sonnet 86 “Was it the proud full sail of his great verse”

The speaker of sonnet 86 “Was it the proud full sail of his great verse” puts on display the skills of a verbal gymnast, acrobat, or tightrope walker, and he always feels confident enough to perform the most difficult movements in his art, as he reaches ever higher for perfection.

Introduction and Text of Sonnet 86 “Was it the proud full sail of his great verse”

With the skills of a verbal gymnast, the speaker in sonnet 86 from the classic Shakespeare 154-sonnet sequence moves along his lines of poetry with the agility of a tightrope walker, and like a skillfully performing acrobat, he always feels confident enough to sway and swagger.

Sonnet 86 “Was it the proud full sail of his great verse”

Was it the proud full sail of his great verse

Bound for the prize of all too precious you,

That did my ripe thoughts in my brain inhearse,

Making their tomb the womb wherein they grew?

Was it his spirit, by spirits taught to write

Above a mortal pitch, that struck me dead?

No, neither he, nor his compeers by night