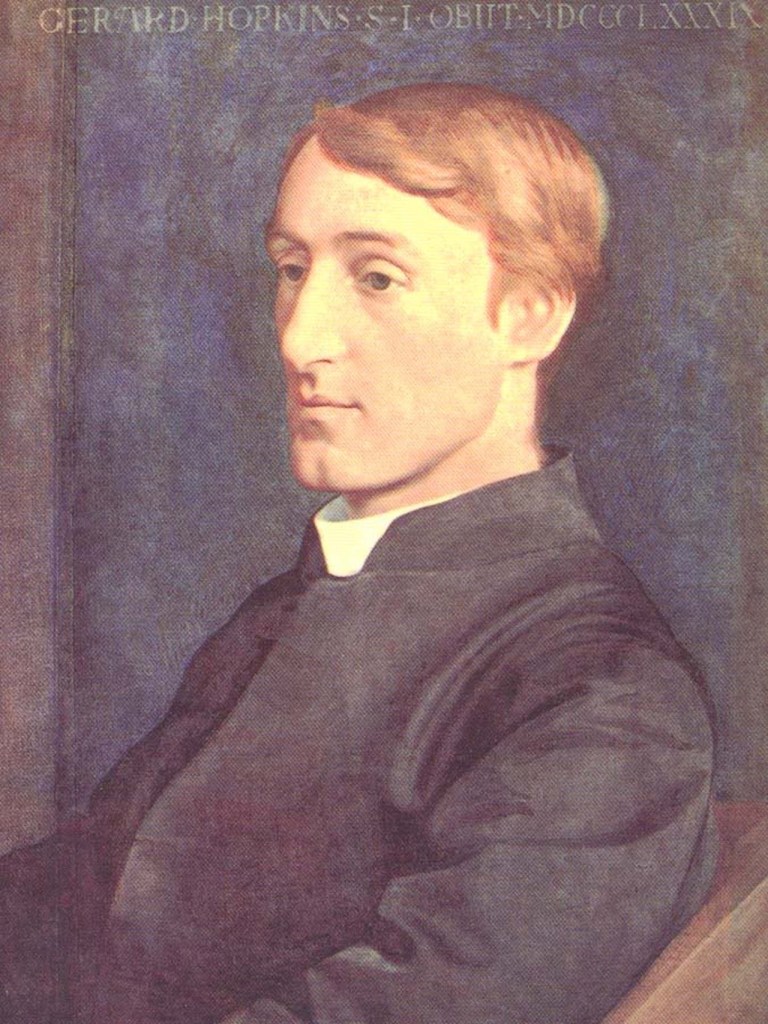

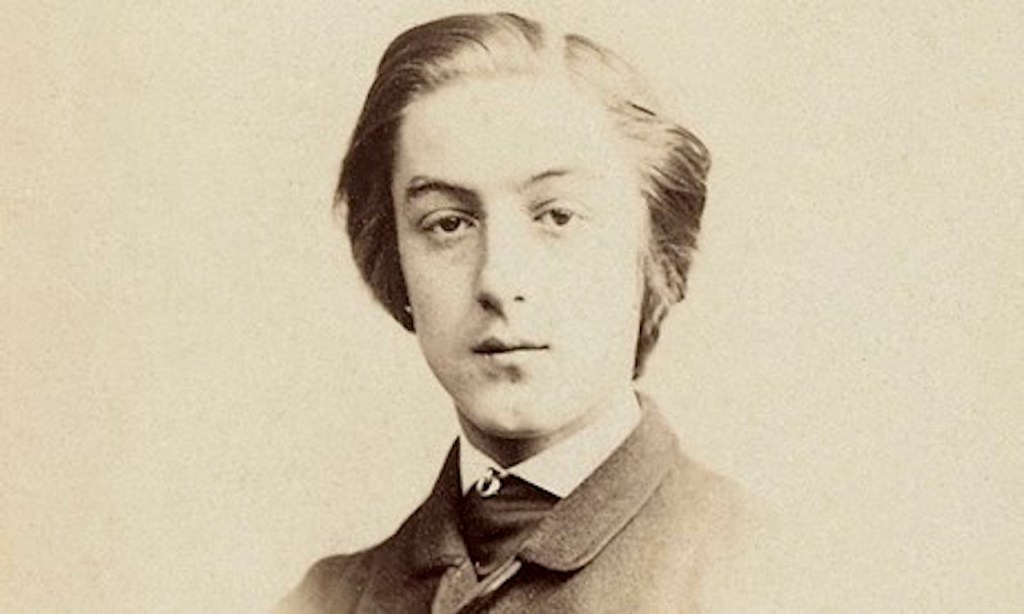

Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “Pied Beauty”

Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “Pied Beauty” is an eleven-line curtal sonnet, dedicated to honoring and praising God for the special beauty of His creation. Father Hopkins coined the term “curtal” to label his eleven-line sonnets.

Introduction and Text of “Pied Beauty”

The speaker in Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem/hymn “Pied Beauty” offers a tribute to the Creator for all things natural and human inspired, with special emphasis on things that are multi-colored, dotted, striped, or patterned in ingenious ways. The poem employs Father Hopkins’ famed sprung rhythm and unique rime scheme: ABCABCDBCDC.

The poem is an eleven-line sonnet called a curtal, a term which Father Hopkins coined to describe the form he employed in certain of his poems, including “Pied Beauty.” While the speaker emphasizes beauty by contrasting things that are widely touted as unpleasant yet possess a certain aura of unique loveliness, he ultimately is affirming that God has made all of creation to reflect various styles of beauty.

Thus, the speaker begins by giving all “glory” to God for all these created things, and he concludes by insisting that God be praised for giving humankind these many patterned objects of beauty.

God and beauty are being weighed in special terms as the speaker creates in his hymn a drama of oppositional tension that results in the creation of balance and harmony. Through appreciation and praise of God for His gifts, humankind learns that balance and harmony in order to complete life’s goals and purposes.

Pied Beauty

Glory be to God for dappled things –

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced – fold, fallow, and plough;

And áll trádes, their gear and tackle and trim.

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.

Recitation of “Pied Beauty”

Commentary on “Pied Beauty”

Father Hopkins’ poem remarkably enlists several synonyms for the important title term “pied.” Those synonyms are dappled, couple-colour, brinded (archaic form of brindled), stipple, and freckled. All of those terms refer to multi-color or dotted patterns that so often appear in nature, that this observant human heart finds divinely inspired.

The poem is, therefore, a hymn honoring the Supreme Creator of all that exists. The piece offers gratitude that the Heavenly Father-Creator has fashioned His world to provide delight for His children.

First Movement: A Pattern of Gratitude

Glory be to God for dappled things –

The speaker begins by glorifying Creator-God for having effected His world to include objects that are multi-spotted and multi-colored. While the speaker undoubtedly offers God all glory to everything in creation, he also glorifies his Creator for not only things but also events. The act of creation remains of particular interest.

The speaker appears to be concentrating on a certain style and pattern that the Almighty has chosen to bestow on certain of His creatures and things. And this devout speaker remains most appreciative of those patterns. Thus, the glory, the honor, and the achievement of God have infused this speaker’s heart and mind to express gratitude.

Second Movement: Examples of All Things Dappled

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced – fold, fallow, and plough;

And áll trádes, their gear and tackle and trim.

The speaker then offers examples of those “dappled” things for which he is offering glory to God. He appreciates the sky that ofttimes appears as multi-colored as a spotted bovine. The speaker is thankful also for the patterns that are dotted over the bodies of “trout that swim.” These stippling patterns resemble small mole-like roses as they decorate the skin of those fish.

This observant, devout speaker also adores the beauty of fallen chestnuts that resemble freshly set-ablaze fire coals on a grate or in a stove. He also uses the “finches’ wings” to exemplify his appreciation for things “dappled.” The wings of finches are often layered strips. The speaker then widens his example to include even the “[l]andscape” or the farmers’ fields that the farmer has “plotted and pieced” in order to plough and “fold” or allow to lie “fallow.”

He finds those patterns to be offering the glory that all “dappled” things offer; thus, he honors them by mentioning them as an example. In fact, every commercial endeavor deserves a nod along with the instruments, their tools, which he refers to as “gear,” “tackle,” and “trim.”

Third Movement: The Spice of Variety

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

In the second stanza, beginning with the third movement, the speaker shifts from simple spotted, multi-colored things to everything remaining that runs against expectation, or that is original and unique, or things that seem simple, and things that appear odd.

Because creation seems to offer an infinite number of styles, patterns, and ways of being, the speaker now wishes to praise God and glorify the Divine Maker by recognizing the Creator’s penchant for variety.

If the old adage “variety is the spice of life” possesses any truth, then certainly the Heavenly Father-God is responsible for the creation of those spices. This speaker thus widens his scope for gratitude.

Fourth Movement: Things That Change

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

The speaker then offers further elucidation for the other components that make up his glossary of things that deserve attention and appreciation because of their having been offered to humankind by the Ultimate Reality, the Supreme Creator of the cosmos.

So the speaker reports that all things, beings, creatures that possess the quality of fickleness or changeability belong to his list of things that honor and give glory to God. Even “freckled” things, of which no one can define the origin, belong to this category.

Those “fickle” and “freckled” things all have several qualities in common; thus, they may exist and behave with speed or move measuredly. They may possess the opposite flavors of sweetness or sourness. Some may also reflect light blazingly while others remain muted and subdued.

Regardless of the unique qualities, they are all part of the Blessèd Creator’s offerings to His children for their pleasure or for their edification or to light whatever pathway they are destined to follow.

Fifth Movement: That Which Does not Change

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.

The speaker then concludes with a command—”Praise him.” In the beginning, he made it clear that he was offering all glory to God for the things He has given through creation. Now he offers his stern command, but before that command, he offers the reason that such praise is due Him.

The Father of all this beauty continues, and although He Himself is “past change” or without the necessity to change Himself, He continues to offer through creation a beauty that is many faceted, multi-colored, multi-stippled, and brindled. And all things remain on a spectrum that humankind cannot duplicate but is surely obligated to honor, appreciate, and glorify in the name of Father God.