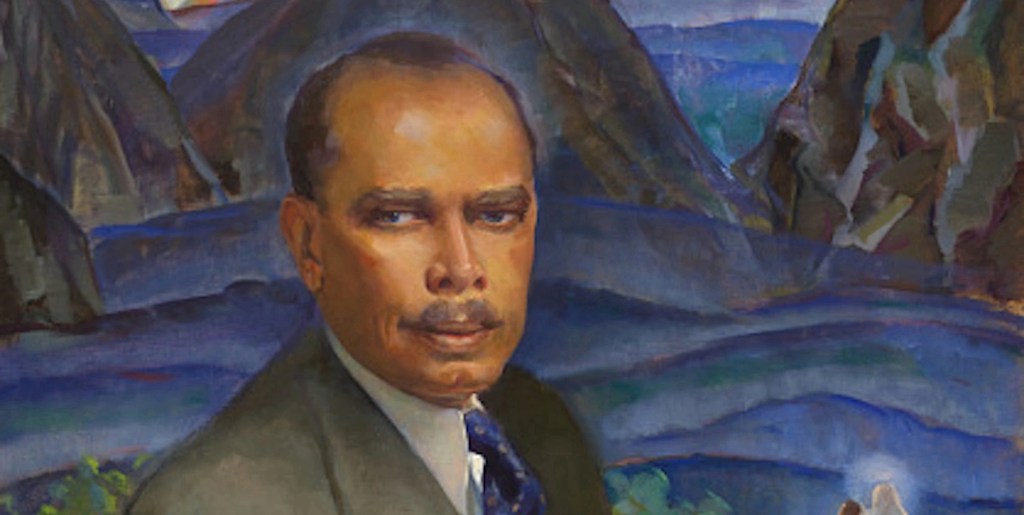

Image: James Weldon Johnson – National Portrait Galley – Smithsonian

James Weldon Johnson’s “Noah Built the Ark”

A poetic retelling of the story about Noah and the Ark, this dramatic poem is one of Johnson’s seven sermons in verse from his collection, God’s Trombones. At certain points in the story, the narrator offers his own interpretations, embellishing the tale and adding further interesting features.

Introduction and Text of “Noah Built the Ark”

James Weldon Johnson’s “Noah Built the Ark” offers an entertaining and educational experience in poetry. Johnson’s clear vision in biblical lore is on full display in his narrative retelling of the Noah and the Ark story from Genesis 6:9–9:17 KJV. The poet is offering an oratory tone in the style of a southern black preacher. His retelling features such plain language that even a child can understand the images and events immediately.

Johnson brought out his collection God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse in 1927. The collection begins with a prayer, “Listen Lord–A Prayer,” and then features seven verse-sermons, “The Creation,” “The Prodigal Son,” “Go Down Death,” “Noah Built the Ark,” “The Crucifixion,” “Let My People Go,” and “The Judgment Day.”

During his lifetime, Johnson had attended many church services throughout the South, and he was inspired by the oratorical style of the many black preachers, whose preaching he admired. A Southerner himself born in Jacksonville, Florida, Johnson had an ear for dialect and rhythms in speech. All of his poetry is enhanced by his talent for language and its specialties of speech.

Noah Built the Ark

In the cool of the day—

God was walking—

Around in the Garden of Eden.

And except for the beasts, eating in the fields,

And except for the birds, flying through the trees,

The garden looked like it was deserted.

And God called out and said: Adam,

Adam, where art thou?

And Adam, with Eve behind his back,

Came out from where he was hiding.

And God said: Adam,

What hast thou done?

Thou hast eaten of the tree!

And Adam,

With his head hung down,

Blamed it on the woman.

For after God made the first man Adam,

He breathed a sleep upon him;

Then he took out of Adam one of his ribs,

And out of that rib made woman.

And God put the man and woman together

In the beautiful Garden of Eden,

With nothing to do the whole day long

But play all around in the garden.

And God called Adam before him,

And he said to him;

Listen now, Adam,

Of all the fruit in the garden you can eat,

Except of the tree of knowledge;

For the day thou eatest of that tree,

Thou shalt surely die.

Then pretty soon along came Satan.

Old Satan came like a snake in the grass

To try out his tricks on the woman.

I imagine I can see Old Satan now

A-sidling up to the woman,

I imagine the first word Satan said was:

Eve, you’re surely good looking.

I imagine he brought her a present, too,—

And, if there was such a thing in those ancient days,

He brought her a looking-glass.

And Eve and Satan got friendly—

Then Eve got to walking on shaky ground;

Don’t ever get friendly with Satan.—

And they started to talk about the garden,

And Satan said: Tell me, how do you like

The fruit on the nice, tall, blooming tree

Standing in the middle of the garden?

And Eve said:

That’s the forbidden fruit,

Which if we eat we die.

And Satan laughed a devilish little laugh,

And he said to the woman: God’s fooling you, Eve;

That’s the sweetest fruit in the garden,

I know you can eat that forbidden fruit,

And I know that you will not die.

And Eve looked at the forbidden fruit,

And it was red and ripe and juicy.

And Eve took a taste, and she offered it to Adam,

And Adam wasn’t able to refuse;

So he took a bite, and they both sat down

And ate the forbidden fruit.—

Back there, six thousand years ago,

Man first fell by woman—

Lord, and he’s doing the same today.

And that’s how sin got into this world.

And man, as he multiplied on the earth,

Increased in wickedness and sin.

He went on down from sin to sin,

From wickedness to wickedness,

Murder and lust and violence,

All kinds of fornications,

Till the earth was corrupt and rotten with flesh,

An abomination in God’s sight.

And God was angry at the sins of men.

And God got sorry that he ever made man.

And he said: I will destroy him.

I’ll bring down judgment on him with a flood.

I’ll destroy ev’rything on the face of the earth,

Man, beasts and birds, and creeping things.

And he did—

Ev’rything but the fishes.

But Noah was a just and righteous man.

Noah walked and talked with God.

And, one day, God said to Noah,

He said: Noah, build thee an ark.

Build it out of gopher wood.

Build it good and strong.

Pitch it within and pitch it without.

And build it according to the measurements

That I will give to thee.

Build it for you and all your house,

And to save the seeds of life on earth;

For I’m going to send down a mighty flood

To destroy this wicked world

And Noah commenced to work on the ark.

And he worked for about one hundred years.

And ev’ry day the crowd came round

To make fun of Old Man Noah.

And they laughed and they said: Tell us, old man,

Where do you expect to sail that boat

Up here amongst the hills?

But Noah kept on a-working.

And ev’ry once in a while Old Noah would stop,

He’d lay down his hammer and lay down his saw,

And take his staff in hand;

And with his long, white beard a-flying in the wind,

And the gospel light a-gleaming from his eye,

Old Noah would preach God’s word:

Sinners, oh, sinners,

Repent, for the judgment is at hand.

Sinners, oh, sinners,

Repent, for the time is drawing nigh.

God’s wrath is gathering in the sky.

God’s a-going to rain down rain on rain.

God’s a-going to loosen up the bottom of the deep,

And drown this wicked world.

Sinners, repent while yet there’s time

For God to change his mind.

Some smart young fellow said: This old man’s

Got water on the brain.

And the crowd all laughed—Lord, but didn’t they laugh;

And they paid no mind to Noah,

But kept on sinning just the same.

One bright and sunny morning,

Not a cloud nowhere to be seen,

God said to Noah: Get in the ark!

And Noah and his folks all got in the ark,

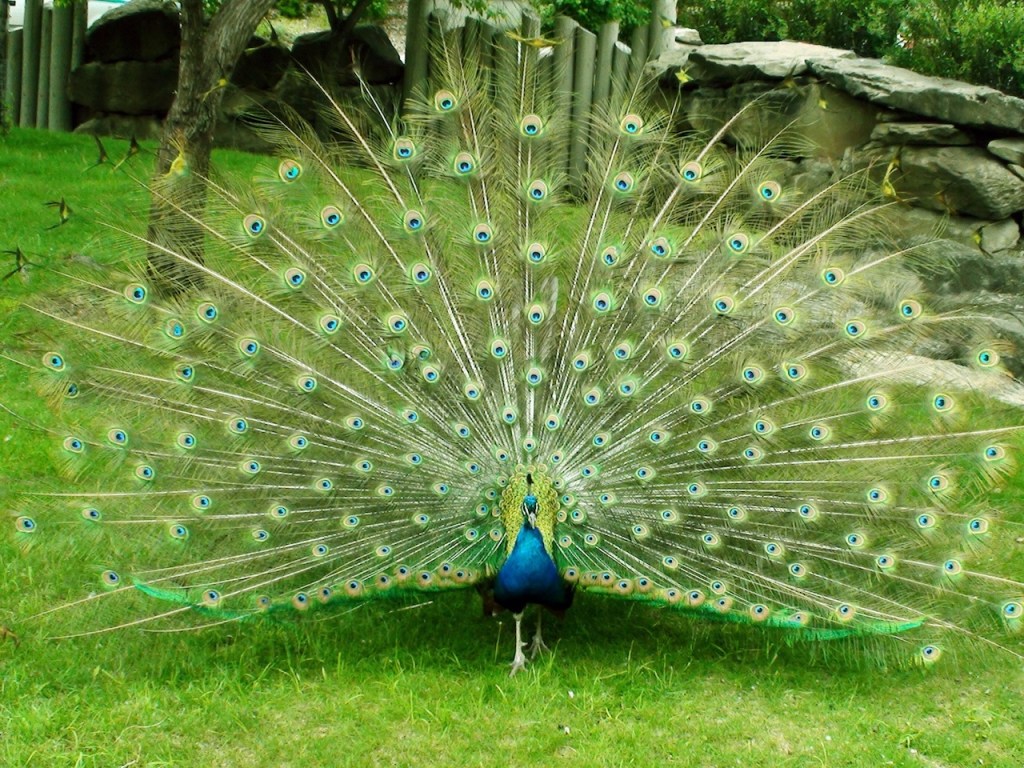

And all the animals, two by two,

A he and a she marched in.

Then God said: Noah, Bar the door!

And Noah barred the door.

And a little black spot begun to spread,

Like a bottle of ink spilling over the sky;

And the thunder rolled like a rumbling drum;

And the lightning jumped from pole to pole;

And it rained down rain, rain, rain,

Great God, but didn’t it rain!

For forty days and forty nights

Waters poured down and waters gushed up;

And the dry land turned to sea.

And the old ark-a she begun to ride;

The old ark-a she begun to rock;

Sinners came a-running down to the ark;

Sinners came a-swimming all round the ark;

Sinners pleaded and sinners prayed—

Sinners wept and sinners wailed—

But Noah’d done barred the door.

And the trees and the hills and the mountain tops

Slipped underneath the waters.

And the old ark sailed that lonely sea—

For twelve long months she sailed that sea,

A sea without a shore.

Then the waters begun to settle down,

And the ark touched bottom on the tallest peak

Of old Mount Ararat.

The dove brought Noah the olive leaf,

And Noah when he saw that the grass was green,

Opened up the ark, and they all climbed down,

The folks, and the animals, two by two,

Down from the mount to the valley.

And Noah wept and fell on his face

And hugged and kissed the dry ground.

And then—

God hung out his rainbow cross the sky,

And he said to Noah: That’s my sign!

No more will I judge the world by flood—

Next time I’ll rain down fire.

Recitation of “Noah Built the Ark”:

Commentary on “Noah Built the Ark”

While the basic story remains a parallel to the original, the narrator offers his own embellishments at certain points that any listener will recognize as departures from the biblical version. This embellishments stem from the narrator’s personal interpretations of the image and events.

First Movement: Original Creation

The actual story featuring Noah and the ark begins in the third movement; the narrator first builds up to the purpose for Noah having to build the ark. Thus, the opening scenes show God just after having created Adam and Eve, summoning them to hold them responsible for their disobedience.

God knows that they have done the one and only thing He had told them not to do: they have eaten of the “tree of knowledge.” God had told them if they disobeyed this one rule, they would die.

Unfortunately, Satan had persuaded Eve to eat of the fruit, making her believe that God was lying to her. Thus, she ate and convinced Adam to eat, and soon they had lost their paradise in Eden.

The narrator creatively describes the characters in his narrative in colorful ways, for example he had “Old Satan” “[a]-silding up the woman.” Then Satan, who moves “like a snake in the grass,” appeals to the woman’s vanity telling her “you’re surely good looking” and then imagining that Satan gave Eve a gift of a “looking-glass” to emphasize her vanity.

Second Movement: Satan’s Seduction

The narrator now goes into some detail as he has Satan seducing Eve to commit the one sin she had been warned against. Satan belts forth a “devilish little laugh” upon hearing that God had told that pair that they would die if they ate of the forbidden fruit. Satan tells Eve, “God’s fooling you.” He then tells her that the fruit she is forbidden is the “sweetest fruit in the garden” and insists that she can enjoy that fruit without dying.

Eve is convinced, eats the fruit, convinces Adam to eat the fruit, and “Man first fell by woman— / Lord, and he’s doing the same today.” The narrator jokingly demonstrates the rift that began between man and woman with the committing of the original sin.

So now mankind multiplied upon the earth, and not only did people increase, but “wickedness and sin” also increased, and kept on increasing until the corruption became “[a]n abomination in God’s sight.”

Third Movement: Corruption and Anger

The corruption made God angry, and the narrator states that “God got sorry that he ever made man.” And then God decides to destroy mankind by flooding the earth. The narrator says that God planned to destroy all life on earth—except “the fishes.”

The narrator is inserting a bit of comedy into his narration because he knows everyone already is aware that God, in fact, instructed Noah to save all animal life. The claim that God would save only the “fishes” is funny, though, because the fishes are the only life forms that can live in the water, a fact that would obviate the necessity of bringing a pair of them into the ark for saving, as was done with the land animals.

Because Noah was not a man of sin and corruption but a “just and righteous man,” who “walked and talked with God,” God chooses Noah to be his instrument in saving a portion of His Creation.

Thus, God instructs Noah to build an ark for which God gives specific instructions: to be made of gopherwood, “good and strong,” pitched inside and out, and according to the dimensions handed down by the Creator.

God tells Noah that He is going to send down a flood to “destroy this wicked world.” But the house/family of Noah would be spared, and God wanted Noah to help Him “save the seeds of life on earth.”

Noah then obeys God’s command, begins building the ark, working for “one hundred years,” experiencing ridicule daily as folks “make fun of Old Man Noah,” quipping, “Where do you expect to sail that boat / Up here amongst the hills?”

Fourth Movement: Building and Preaching

Noah remains undeterred, working on the ark, but every now and then, he would cease his ark building and offer a sermon. In his sermon, he would tell the “sinners” that they needed to repent because God was going to send “rain down rain on rain.”

Because of all the sinning and corruption, God’s wrath would “drown this wicked world.” Noah encourages the sinners to turn their lives around while there is still time for “God to change his mind.” In response to Noah, a laughing young reprobate quips: “This old man’s / Got water on the brain.” And then everyone else laughs.

Paying no attention to Noah’s warning, they keep on sinning. Then on a bright, sunny morning, the day had come. God instructs Noah to gather pairs of animals and take them along with his family into the ark and “Bar the door!” Then similar to ink spilling over a page, a black spot in the sky begins to spread, and the rain begins—pouring rain for forty days and night.

And many sinners come to the ark “a-running” and “a-swimming” around the ark, pleading to be let in, but it is too late. Though the sinners continue to weep and wail, “Noah’d done barred the door.”

Fifth Movement: The Promise

The narrator then describes the flooded earth, where trees, hills, mountain tops all “slipped underneath the waters.” And for “twelve long months,” the ark sails on a sea that possesses no shore.

Finally, the waters begin to recede, and ark settles down on the tall peak of Mount Ararat. A dove appears to Noah with an olive leaf, altering him that the flood is over, and anew beginning is at hand for all of the inmates of the Ark.

After leaving the ark, the righteous Noah “wept and fell on his face / And hugged and kissed the dry ground.” God then stretches a “rainbow across the sky” and promises Noah that the rainbow would be his reminder that He would never again “judge the world by flood.”

But then God warns that “Next time I’ll rain down fire.” Throughout his retelling of the Noah and the Ark story, the narrator has often added embellishments stemming from his own idiosyncratic interpretations.

The narrator’s final embellishment that God promised to end the world next by fire cannot be found in the biblical KJV version of that tale, but many instances in that version of the Holy Scripture do imply that God might employ the fire element the next time He feels compelled to destroy His Creation.