Image: Silhouette – Couple

Fiction Alert!

This story is fiction.

It does not depict any real person or actual event.

Falling Grace

Grace Jackson began her freshman year at Ball State Teachers College with hopes of becoming an English teacher like her favorite high school teacher Mrs. Daisy Slone, an avid Shakespeare fan and scholar.

Grace Goes to College

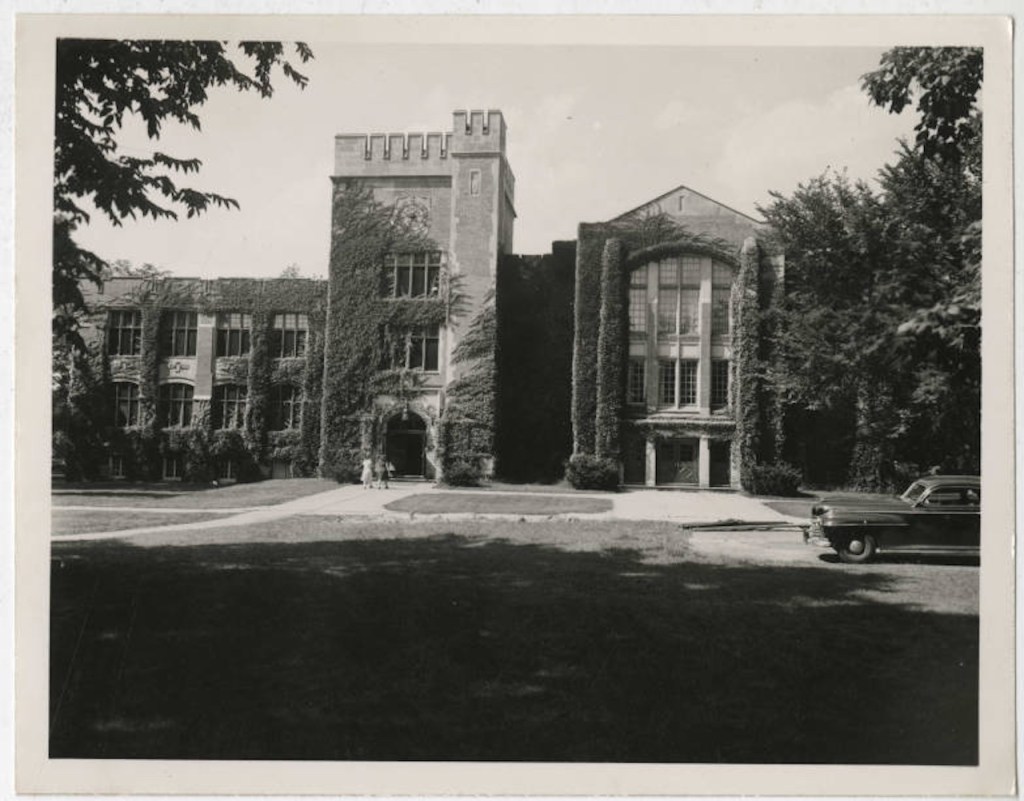

In the Hoosier heartland of America, where cornfields stretch like the dreams of the early American settlers, stood Ball State Teachers College (later renamed Ball State University), a bastion of teacher education.

There among the ten-thousand or so students and armies of administrators came Grace Jackson, a freshman with eyes like the last autumn leaves—vibrant yet tinged with the inevitability of fall.

Grace was majoring in English, where in a world woven from words, each sentence threaded itself into the tapestry of her young life. She had brought her treasure trove of books in one suitcase, and her clothes in much smaller one. She had marveled at all the gear other students had carted into the dorms.

Her days were spent plumbing the nuances of Shakespeare and the Romantic tropes of Wordsworth, but her heart and hormones were captivated by a different history, one not bound by books but by the circling rhythm of a forbidden dance.

A Professor’s Gaze

Professor Ed Stewart, her professor in general studies American history, possessed eyes that seemed to have witnessed centuries, even as they betrayed the youth of a young scholar, for he was less than a decade older than Grace. In class, he held her gaze, thrilling to smiles this young co-ed flashed his way.

Those lectures became a prelude to the symphony of secrets they would share. They soon began to meet outside of class; at first, she just needed some advice about extra reading. Then they met just to talk and walk and finally . . .

For Grace, their affair became a clandestine sonnet, whispered in the shadows of the old library, where the dust of ancient texts seemed to conspire in silence. Here, time felt suspended, each stolen moment of hand-holding, passionate kissing, and sweet talk—all a defiance against the ticking clock of morality.

The sad fact was that Professor Stewart was a married man with two young daughters, but that marriage had long soured, and he felt unhappily tethered to a life with Darlene, whose laughter had once been the melody of his days, now the echo of a song he no longer sang.

Darlene had become a born-again Christian in a very strict denomination called Hard Shell Baptist, and Ed chafed under her constant nagging that he attend church with her and the girls. At ages 11 and 9, the daughters easily sided with the mother making Ed’s life a constant, bitter struggle with adversity

Moonlight and Shadows

One late evening, when the campus was fairly deserted, under the cloak of a moon that seemed to understand their forbidden desire, Ed led Grace to a secluded alcove in the shadows between the college library and the assembly hall.

The air was lightly scented with the fragrance of burning leaves from the neighborhood surrounding the school, and the stars above whispered secrets only lovers could hear. Here, in this shadowed hide-away, they sought solace that seemed to escape them in the cold light of day

Ed took her hand and whispered, “Now, we are not separated.” Ed’s touch was like the first pages of a cherished book, gentle yet eager to explore. His lips pressed against Grace’s, and she felt that her body would melt into his.

A rustling of clothing and their bodies sealed together in a passionate embrace. Grace felt a stab of virginal pain but then dismissed it as her mind flew into the utter romance of consummation.

Ed quietly spoke of a love that transcends the boundaries of their world. “We are but a footnote in history,” he whispered, his breath warm against her neck, “but let us write our own chapter tonight.” And he took her body again in a passionate rush

Their bodies, entwined like the ivy around the old stone walls, continued to pump with the rhythm of a salacious sonnet. This love scene, hidden from the prying eyes of the world, was their rebellion. They rationalized that it was their silent scream against the life they could not openly claim.

Grace’s Fall

Fall turned to winter, and with the first frost, Grace’s heart and mind hardened. She saw Darlene not as a person but as an obstacle, a leaf that refused to fall, clinging to a tree that should now be hers.

Grace etched her plan. She would feign the need for help with a project, one that she knew was dear to Darlene’s heart, Campus Kids of Christ.

On a Monday night, under a moon that seemed to mourn, Grace visited the Stewart’s modest home, while the professor and the girls were away. The plan was simple, as sinister as the frost that nipped at the earth’s warmth.

Darlene greeted her with a smile, unaware of the storm she harbored. Grace’s words were sweet, like poisoned honey, as she asked for help with a project, to raise money for the group CKC.

In the quiet kitchen, where Darlene turned her back to pour tea, Grace’s hand, guided by a dark resolve, found the handle of the knife. The act was swift, a betrayal that whispered through the steam of the kettle, sealing fate as irrevocably as the first snow seals the ground.

The Frame of an Innocent

Grace stole out quickly into the night that seemed to swallow her like the silence after a gunshot, but in her wake, she planted seeds of deceit. She decided to frame Lester Phillips, a fellow student, whose jealousy over grades made him a plausible suspect. The framing was meticulous, a work of dark art.

First, Grace began to plant clues. She had seen Lester’s disdain for Professor Stewart in class, his bitter accusations of favoritism. She used this knowledge, planting a scarf with Lester’s initials near the crime scene. She had taken it from his locker one day, a small theft that would later become a noose around his neck.

She then concocted a false alibi. She made sure Lester was seen arguing with Darlene at a university event a week before the murder, their voices raised in the heat of academic rivalry. Grace whispered rumors, ensuring this altercation was remembered.

Grace then borrowed several sheets of paper from Lester’s personalized stationery under the guise of needing to write a letter to her mother, and she hadn’t had time to go to the bookstore to purchase her own writing paper.

On Lester’s stationery, she composed and then sent a letter to Darlene; the missive was filled with veiled threats and anger, suggesting a buildup of hostility.

Then finally, in her own room, she left notes about Lester’s supposed obsession with Darlene, scribblings that hinted at an unhealthy fixation, all written in her hand but styled to mimic Lester’s handwriting, as she had done with his stationery. She had practiced Lester’s handwriting style from a paper he left behind in class.

Truth Will Not Hide

Lester, with his loud protests and defensive demeanor, became the scapegoat, his life unraveling like a poorly knitted scarf in the hands of an unjust fate. But shadows, even those cast by the cunning, have a way of revealing their source.

But the college, as a microcosm of the world, was not immune to whispers. The police, methodical in their search for truth, found discrepancies in Grace’s alibi, her motive buried but not deep enough. The poetry of her deception was undone by the prosaic truth of evidence.

Grace could never account satisfactorily for her visit to the Stewart home at the time of Darlene’s murder. Too many roommates in her dorm all knew where she had gone that night. And the blood on her coat and boots proved to be Darlene’s, not her own nose bleed that she had tried to claim.

Sentencing Grace

Grace’s trial was an intense spectacle, the courtroom a stage where her life was dissected with the precision of a scientist. The judge, an old man with eyes that had seen too many stories end badly, announced that the jury had found her guilty.

The judge sentenced her to death, a final act in a drama she had orchestrated but could not control. In addition to the murder, her attempt to frame an innocent man swayed the judge and jury to impose the death penalty.

In her cell, Grace awaited the end, her world now a stark contrast to the vibrant one she had envisioned. In her cell, there were no books, no metaphors to escape into, only the cold reality of bars and the echo of her own heartbeat. She wrote her last poem on the wall, words etched with the stub of a pencil, a confession and a lament:

The gray cell and the black bars seem to pray

As I pen my fate: My love has melted away

From my heart. His stubborn wife

Clinging to my love brought death her way.

She fell like a leaf under a cold, hard moon.

She stole my innocence, so I die at noon.

The imagery of her life became clear in these lines—her ambitious delusions, her faux love, her crime, all intertwined like the roots of an old oak, now exposed. The poetry that once colored her world was now her shroud, each word a reminder of the affection she sought and the darkness she embraced.

As she continued to think of her former lover, she continued in a depraved solace knowing that although she would never cleave her body to his again, neither would Darlene, who was now nothing more than an object of hatred.

An insane, silent cry kept ringing through her brain that it was all Darlene’s fault that she was now facing death before reaching the age of twenty.

On the day of her execution, the sky was as gray as the walls of her cell, the air heavy with the scent of rain, not unlike the day she first met Professor Stewart. As she walked her final steps, she looked up, perhaps seeking redemption or merely an end to the story she had written with blood instead of ink.

The Legend

The college moved on, its halls echoing with old legends, new stories, new lives, but in the old library, where their affair began, one could almost feel the ghost of Grace Jackson, her passion, her folly, her poetry. The leaves outside turned, year after year, a reminder of life’s cycle, of love’s complexity, and the tragic, tumultuous, terrifying power of desire.

And Ed, left with the weight of his part in this tragedy, returned to his lectures, his words now haunted by the specter of what was once his heart’s desire, turned to pity by the very hands he once held.

He felt that he could not face his daughters after the shame he brought to the family, so when Darlene’s sister Natalie, who lived in Georgia, insisted on seeking custody of the girls, he readily bent to Natalie’s wishes and allowed his daughter to grow up without him.

Thus, the tale of Grace Jackson and Professor Ed Stewart became part of the legend of this Indiana heartland college, a dark narrative woven into the fabric of its history, a cautionary tale of attraction, ambition, and the fatal missteps of those who dare to step outside of the boundaries of moral truth.

Image: Ball State Teachers College Library and Assembly Hall