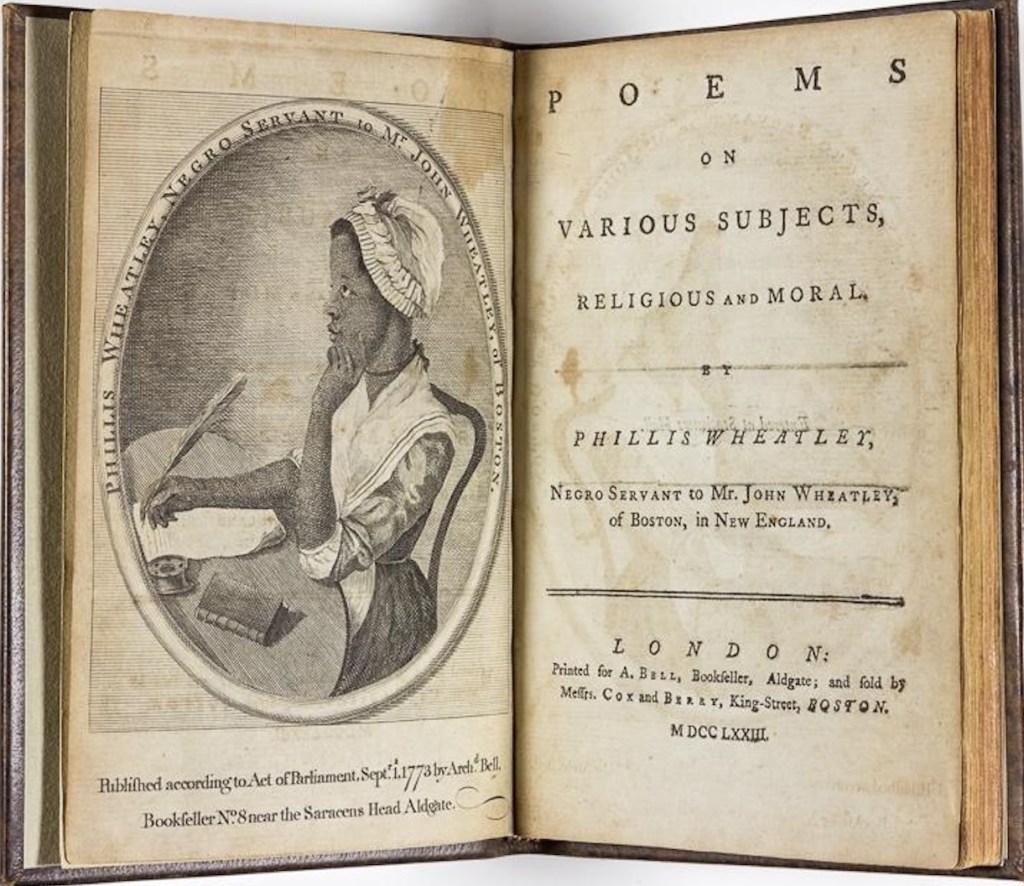

Image: Phillis Wheatley: Engraving, reproduced from her book, “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral.” London, 1773. New York Public Library

Phillis Wheatley’s “A Hymn to the Evening”

The speaker in Phillis Wheatley’s “A Hymn to the Evening” offers her spiritually motivated song/prayer as a tribute to evening, the part of the day when nightly slumber is arriving in all its glory.

Introduction and Text of “A Hymn to the Evening”

The speaker in Phillis Wheatley’s “A Hymn to the Evening” is delighting in the beauty surrounding her. She is especially cognizant of how all events seem to be accruing for the purpose of making a beautiful day to close with a delightful, colorful evening.

The speaker finds the evening sky glorious as it yield the “deepest red” hue, as all other various colors are also displaying across the sky. She also observes the scenery around her on earth; she takes measure of streams and especially the songs of birds. She demonstrates her love and admiration for the creation that the Divine Creator has bestowed on all of His children.

The poem consists of nine riming couplets, with the first couplet featuring an internal rime as well as an end rime. The second couplet features the rare poetic device, similar to personification, of metaphorically comparing a gentle wind to a bird. The couplet-formed verse lends to the high tone with which the poet has flavored her hymn.

By labeling her poem a hymn, the poet has elevated its purpose from a simple tribute to a time of day, to a supplication for gratitude. As she has observed much beauty about her and is thankful for the opportunity to engage that loveliness, she wishes that same gratitude for all of humankind.

The speaker is also offering her song as she is praying that the simple act of appreciating one’s environment may uplift and keep humankind on a virtuous path, on which avoidance of all that cause harm and corruption may be avoided.

A Hymn to the Evening

Soon as the sun forsook the eastern main

The pealing thunder shook the heav’nly plain;

Majestic grandeur! From the zephyr’s wing,

Exhales the incense of the blooming spring.

Soft purl the streams, the birds renew their notes,

And through the air their mingled music floats.

Through all the heav’ns what beauteous dies are spread!

But the west glories in the deepest red:

So may our breasts with ev’ry virtue glow,

The living temples of our God below!

Fill’d with the praise of him who gives the light,

And draws the sable curtains of the night,

Let placid slumbers sooth each weary mind,

At morn to wake more heav’nly, more refin’d;

So shall the labours of the day begin

More pure, more guarded from the snares of sin.

Night’s leaden sceptre seals my drowsy eyes,

Then cease, my song, till fair Aurora rise.

Commentary on “A Hymn to the Evening”

The speaker is inspired by the beauty of the day’s events that she has been observing both in the sky and on the land around her, as the end of the day is arriving. She turns her simple awareness into a tribute and supplication for all humankind’s spiritual betterment.

First Movement: Opening of Day

Soon as the sun forsook the eastern main

The pealing thunder shook the heav’nly plain;

Majestic grandeur! From the zephyr’s wing,

Exhales the incense of the blooming spring.

The speaker opens her tribute by describing how the day had begun with a thunder storm as soon as morning had ended. She finds the event an example of “[m]ajestic grandeur.” On a soft gentle breeze, the fragrance of spring’s flowers came wafting.

The inspired speaker then has the sun “forsaking” its domain in the east. After having arisen, the big star does does not wait but keeps traveling across the sky, literally, forsaking all it leaves behind. By beginning with the opening of the day, the speaker then gathers images throughout the day that accumulate to a marvelous evening at the close of that day.

The speaker describes the thunder as “pealing” and that it colorfully caused to tremble the area around it. The thunder strikes the speaker as a grand event, one fitting to collect as evidence that a glorious evening may be in the offing.

The first couplet includes an internal rime, as well as and end rime: “forsook – shook.” Also, interestingly, the poet has employed avianification (akin to the device, “personification”) by metaphorically giving a gentle breeze a “wing,” a feature belonging to a bird.

Second Movement: The Colors of Beauty

Soft purl the streams, the birds renew their notes,

And through the air their mingled music floats.

Through all the heav’ns what beauteous dies are spread!

But the west glories in the deepest red:

The speaker then notes that the streams are babbling gently and birds are continuing to offer their songs to the atmosphere. The birds’ music seems to blend with other features of the landscape as their singular notes continue to waft on the breeze.

She has the stream purling, instead of merely babbling; this speaker is colorfully describing each natural object for the purpose of incorporating them into her collection of images, which she will offer to the day’s end.

The speaker then remarks that through the sky swirl many various colors that she deems to be “beauteous,” as they stretch across the blue expanse. However, she finds those hues that appear in “the west” to be the “deepest red,” and she implies that the oncoming sunset will cap the day in a marvelous and glorious procession.

The speaker finds unusual as well as deeply spiritual ways of describing what she sees. She is offering her words, her images, and her thoughts to her Divine Creator. Thus, she remains careful to choose each image and description with precision, for example, the west does not merely feature “deepest red,” but it also “glories” in that color. Making each word and each image work its magic demonstrates the poet’s skill and mastery of her art.

Third Movement: A Supplication for Gratitude

So may our breasts with ev’ry virtue glow,

The living temples of our God below!

Fill’d with the praise of him who gives the light,

And draws the sable curtains of the night,

The speaker then turns to the hearts and minds of humanity, prayerfully supplicating for those hearts and minds to “glow,” filled with “ev’ry virtue.” She hopes that the lives of all humankind become and remain “temples” on earth dedicated to the Belovèd Creator. She includes all of humanity in her supplication as she effuses, “may our breasts” glow as living temples.

The speaker wishes that all of humanity become full of praise for the Blessèd Creator of the cosmos; that Creator, Who had given “the light” also will close the “curtains of the night”: again the speaker has shown her marvelous skill by describing those “curtains” as “sable.”

The speaker then prays that all of humanity may sleep peacefully and become refreshed so that the next day’s existence becomes “more heav’nly, more refin’d.” She hopes and prays that each day will find humanity to be living more and more on a grand scale of plain living and high thinking. As she includes herself in her prayer, she demonstrates her humility and deep inner awareness of the needs of all humankind.

Fourth Movement: Prayer for Virtuous Living

Let placid slumbers sooth each weary mind,

At morn to wake more heav’nly, more refin’d;

So shall the labours of the day begin

More pure, more guarded from the snares of sin.

Night’s leaden sceptre seals my drowsy eyes,

Then cease, my song, till fair Aurora rise.

After a night’s peaceful, invigorating rest of the body and mind, each child of the Divine Creator may begin his/her work, chastened and strengthened by the gratitude of finding a safe harbor in the Blessèd Lord.

The speaker prays that all be turned from “the snares of sin.” Again, the speaker is demonstrating her ethical and moral strength as she wishes for all of humankind the same rectitude she desires for herself.

The speaker then closes her song of praise for the Belovèd Creator’s beauty in creation by colorfully comparing the closing of her own sleepy eyes—her “drowsy eyes”—to being touched by a royal, magical wand.

She then bids her hymn end and allow her the sleep she now needs; thus, she prays for herself a soothing slumber until morning, when the Roman goddess, “Aurora,” brings in a new day with dawn.