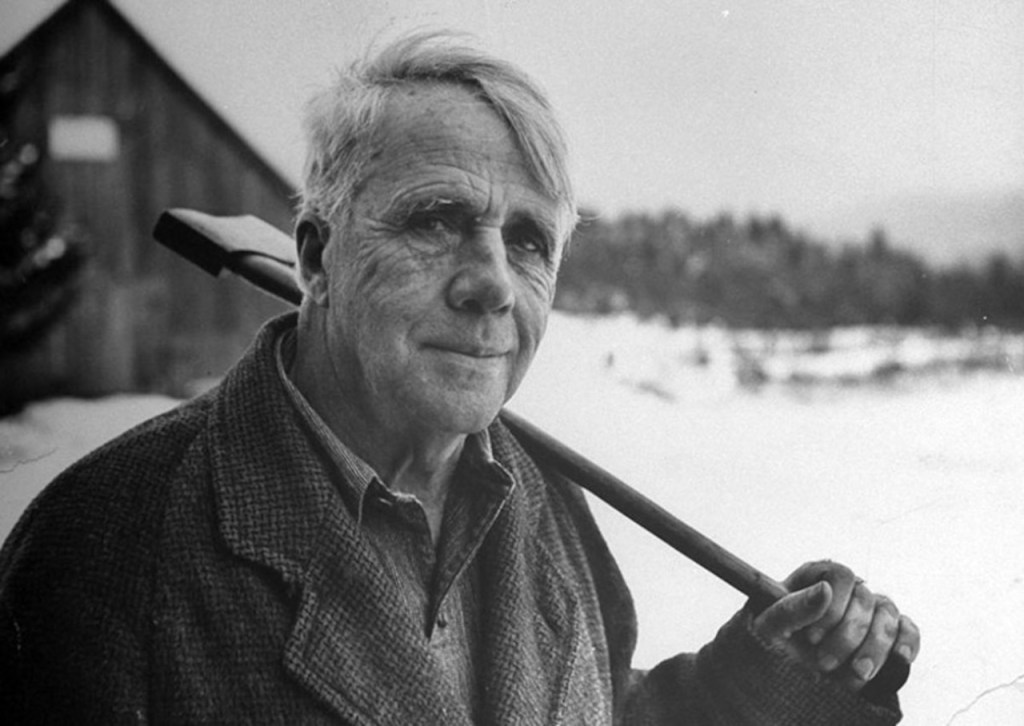

Robert Frost’s “Birches”

RobertFrost’s “Birches” is one of his most famous poems. It features a speaker looking back on a boyhood experience that he cherishes and would like to do again. Unfortunately, this “tricky poem” has suffered ludicrous readings that insert onanism into its innocent nostalgia.

Introduction and Text of “Birches”

The speaker in Robert Frost’s “Birches” is musing on a boyhood activity that he enjoyed. As a “swinger of birches,” he rode trees and felt the same euphoria that children feel who experience carnival rides such as ferris wheels or tilt-a-whirls.

The speaker also gives a rather thorough description of birch trees after an ice-storm. In addition, he makes a remarkable statement that hints at the yogic concept of reincarnation: “I’d like to get away from earth awhile / And then come back to it and begin over.” However, after making that striking remark, he backtracks perhaps thinking such a foolish thought might disqualify him from rational thought.

That remark however demonstrates that as human beings our deepest desires correspond to truth in ways that our culture in the Western world has plastered over through centuries of materialistic emphasis on the physical level of existence. The soul knows the truth and once in a blue moon a poet will stumble across it, even if he does not have the ability to fully recognize it.

Birches

When I see birches bend to left and right

Across the lines of straighter darker trees,

I like to think some boy’s been swinging them.

But swinging doesn’t bend them down to stay

As ice-storms do. Often you must have seen them

Loaded with ice a sunny winter morning

After a rain. They click upon themselves

As the breeze rises, and turn many-colored

As the stir cracks and crazes their enamel.

Soon the sun’s warmth makes them shed crystal shells

Shattering and avalanching on the snow-crust—

Such heaps of broken glass to sweep away

You’d think the inner dome of heaven had fallen.

They are dragged to the withered bracken by the load,

And they seem not to break; though once they are bowed

So low for long, they never right themselves:

You may see their trunks arching in the woods

Years afterwards, trailing their leaves on the ground

Like girls on hands and knees that throw their hair

Before them over their heads to dry in the sun.

But I was going to say when Truth broke in

With all her matter-of-fact about the ice-storm

I should prefer to have some boy bend them

As he went out and in to fetch the cows—

Some boy too far from town to learn baseball,

Whose only play was what he found himself,

Summer or winter, and could play alone.

One by one he subdued his father’s trees

By riding them down over and over again

Until he took the stiffness out of them,

And not one but hung limp, not one was left

For him to conquer. He learned all there was

To learn about not launching out too soon

And so not carrying the tree away

Clear to the ground. He always kept his poise

To the top branches, climbing carefully

With the same pains you use to fill a cup

Up to the brim, and even above the brim.

Then he flung outward, feet first, with a swish,

Kicking his way down through the air to the ground.

So was I once myself a swinger of birches.

And so I dream of going back to be.

It’s when I’m weary of considerations,

And life is too much like a pathless wood

Where your face burns and tickles with the cobwebs

Broken across it, and one eye is weeping

From a twig’s having lashed across it open.

So was I once myself a swinger of birches.

And so I dream of going back to be.

It’s when I’m weary of considerations,

And life is too much like a pathless wood

Where your face burns and tickles with the cobwebs

Broken across it, and one eye is weeping

From a twig’s having lashed across it open.

I’d like to get away from earth awhile

And then come back to it and begin over.

May no fate willfully misunderstand me

And half grant what I wish and snatch me away

Not to return. Earth’s the right place for love:

I don’t know where it’s likely to go better.

I’d like to go by climbing a birch tree,

And climb black branches up a snow-white trunk

Toward heaven, till the tree could bear no more,

But dipped its top and set me down again.

That would be good both going and coming back.

One could do worse than be a swinger of birches.

Reading

Commentary on “Birches”

Robert Frost’s “Birches” is one of the poet’s most famous and widely anthologized poems. And similar to his famous poem “The Road Not Taken,” “Birches” is also a very tricky poem, especially for certain onanistic mindsets.

First Movement: A View of Arching Birch Trees

When I see birches bend to left and right

Across the lines of straighter darker trees,

I like to think some boy’s been swinging them.

But swinging doesn’t bend them down to stay

As ice-storms do. Often you must have seen them

Loaded with ice a sunny winter morning

After a rain. They click upon themselves

As the breeze rises, and turn many-colored

As the stir cracks and crazes their enamel.

The speaker begins by painting a scene wherein birch trees are arching either “left or right” and contrasting their stance with “straighter darker tree.” He asserts his wish that some young lad has been riding those trees to bend them that way.

Then the speaker explains that some boy swinging on those trees, however, would not bend them permanently “[a]s ice-storms do.” After an ice-storm they become heavy with the ice that begins making clicking sounds. In the sunlight, they “turn many-colored” and they move until the motion “cracks and crazes their enamel.”

Second Movement: Ice Sliding off Trees

Soon the sun’s warmth makes them shed crystal shells

Shattering and avalanching on the snow-crust—

Such heaps of broken glass to sweep away

You’d think the inner dome of heaven had fallen.

They are dragged to the withered bracken by the load,

And they seem not to break; though once they are bowed

So low for long, they never right themselves:

You may see their trunks arching in the woods

Years afterwards, trailing their leaves on the ground

Like girls on hands and knees that throw their hair

Before them over their heads to dry in the sun.

The sun then causes the crazy ice to slide off the trees as it “shatter[s] and avalanch[es]” on to the snow. Having fallen from the trees, the ice looks like big piles of glass, and the wind comes along and brushes the piles into the ferns growing along the road.

The ice has caused the trees to remain bent for years as they continue to “trail their leaves on the ground.” Seeing the arched birches puts the speaker in mind of girls tossing their hair “over the heads to dry in the sun.”

Third Movement: Off on a Tangent

Before them over their heads to dry in the sun.

But I was going to say when Truth broke in

With all her matter-of-fact about the ice-storm

I should prefer to have some boy bend them

As he went out and in to fetch the cows—

Some boy too far from town to learn baseball,

Whose only play was what he found himself,

Summer or winter, and could play alone.

One by one he subdued his father’s trees

By riding them down over and over again

Until he took the stiffness out of them,

And not one but hung limp, not one was left

For him to conquer. He learned all there was

To learn about not launching out too soon

And so not carrying the tree away

Clear to the ground. He always kept his poise

To the top branches, climbing carefully

With the same pains you use to fill a cup

Up to the brim, and even above the brim.

Then he flung outward, feet first, with a swish,

Kicking his way down through the air to the ground.

At this point, the speaker realizes that he has gone off on a tangent with his description of how birches get bent by ice-storms. His real purpose he wants the reader/listener to know lies in another direction. That the speaker labels his aside about the ice-storm bending the birch tree “Truth” is somewhat bizarre. While his colorful description of the trees might be a true one, it hardly qualifies as “truth” and with a capital “T” no less.

“Truth” involves issues that relate to eternal verities, especially of a metaphysical or spiritual nature—not how ice-storms bend birch trees or any purely physical detail or activity. The speaker’s central wish in this discourse is to reminisce about this own experience of what he calls riding trees as a “swinger of birches.” Thus he describes the kind of boy who would have engaged in such an activity.

The boy lives so far from other people and neighbors that he must make his own entertainment; he is a farm boy whose time is primarily taken up farm work and likely some homework for school. He has little time, money, inclination for much of a social life, such as playing baseball or attending other sports games.

Of course, he lives far from the nearest town. The boy is inventive, however, and discovers that swinging on birch trees is a fun activity that offers him entertainment as well as the acquisition of a skill. He had to learn to climb the tree to the exact point where he can then “launch” his ride.

The boy has to take note of the point and time to swing out so as not to bend the tree all the way to ground. After attaining just the right position on the tree and beginning the swing downward, he can then let go of the tree and fling himself “outward, feet first.” And “with a swish,” he can begin kicking his feet as he soars through the air and lands on the ground.

Fourth Movement: The Speaker as a Boy

So was I once myself a swinger of birches.

And so I dream of going back to be.

It’s when I’m weary of considerations,

And life is too much like a pathless wood

Where your face burns and tickles with the cobwebs

Broken across it, and one eye is weeping

From a twig’s having lashed across it open.

So was I once myself a swinger of birches.

And so I dream of going back to be.

It’s when I’m weary of considerations,

And life is too much like a pathless wood

Where your face burns and tickles with the cobwebs

Broken across it, and one eye is weeping

From a twig’s having lashed across it open.

Now the speaker reveals that he himself once engaged in the pastime of swinging on birches. That is how he knows so much about the difference it makes of a boy swinging on the trees and ice-storms for the arch of the trees. And also that he was once a “swinger of birches” explains how he knows the details of just how some boy would negotiate the trees as he swung on them.

The speaker then reveals that he would like to revisit that birch-swinging activity. Especially when he is tired of modern-day life, running the rat-race, facing all that the adult male has to contend with in the workday world, he day-dreams about this carefree days of swinging on birch trees.

Fifth Movement: Getting off the Ground

I’d like to get away from earth awhile

And then come back to it and begin over.

May no fate willfully misunderstand me

And half grant what I wish and snatch me away

Not to return. Earth’s the right place for love:

I don’t know where it’s likely to go better.

I’d like to go by climbing a birch tree,

And climb black branches up a snow-white trunk

Toward heaven, till the tree could bear no more,

But dipped its top and set me down again.

That would be good both going and coming back.

One could do worse than be a swinger of birches.

The speaker then asserts his wish to leave earth and come back again. Likely this speaker uses the get-away-from-earth notion to refer to the climbing of the birch tree, an act that would literally get him up off the ground away from earth. But he quickly asks that “no fate willfully misunderstand” him and snatch him away from the earth through death—he “knows” that such a snatch would not allow him to return.

The speaker then philosophizes that earth is “the right place for love” because he has no idea that there is any other place it could “go better.” So now he clarifies that he simply would like to climb back up a birch tree and swing out as he did when a boy: that way he would leave earth for the top of the tree and then return to earth after riding it down and swinging out from the tree. Finally, he offers a summing up of the whole experience that being swinger of birches—well, “one could do worse.”

Image: Bent Birch– hotographer: Dale L. Hugo – Universities Space Research Association

Tricked by Robert Frost’s “Birches”

Robert Frost claimed that his poem, “The Road Not Taken,” was a very tricky poem. He was correct, but other poems written by Frost have proved to be tricky as well. This poem is clearly and unequivocally a nostalgic piece by a speaker looking back at a boyhood pastimes that he cherishes. Some readers have fashioned an interpretation of masturbatory activity from this poem.

Robert Frost’s second most widely known poem “Birches” has suffered an faulty interpretation that equals the inaccurate call-to-nonconformity so often foisted onto “The Road Not Taken.” At times when readers misinterpret poems, they demonstrate more about themselves than they do about the poem. They are guilty of “reading into a poem” that which is not there on the page but is, in fact, in their own minds.

Readers Tricked by “Birches”

Robert Frost claimed that his poem “The Road Not Taken” was a tricky poem, but he must have known that any one of his poems was likely to trick the over-interpreter or the immature, self-involved reader. The following lines from Robert Frost’s “Birches” have been interpreted as referring to a young boy learning the pleasures of self-gratification:

One by one he subdued his father’s trees

By riding them down over and over again

Until he took the stiffness out of them,

And not one but hung limp, not one was left

For him to conquer. He learned all there was

To learn about not launching out too soon

About those lines, Elizabeth Gregory, who used to post on the now defunct site Suite101, once claimed: “The lexical choices used to describe the boy’s activities are unmistakably sexual and indicate that he is discovering more than a love of nature.”

Indeed, one could accurately interpret that the boy is discovering something “more than the love of nature,” but what he is discovering (or has discovered actually since the poem is one of nostalgic looking back) is the spiritual pull of the soul upward toward heaven, not the downward sinking of the mind into sexual dalliance.

In the Mind of the Beholder, Not on the Page

Gregory’s interpretation of sexuality from these lines simply shows the interpretive fallacy of “reading into” a poem that which is not there, and that reader’s proposition that “the boy’s activities are unmistakably sexual” exhausts reason or even common sense.

The “lexical choices” that have tricked this reader are, no doubt, the terms “riding,” “stiffness,” “hung limp,” and “launching out too soon.” Thus that reader believes that Robert Frost wants his audience to envision a tall birch tree as a metaphor for a penis: at first the “tree (male member)” is “stiff (ready for employment),” and after the boy “rides them (has his way with them),” they hang “limp (are satiated).”

And from riding the birches, the boy learns to inhibit “launching out too soon (premature release).” It should be obvious that this is a ludicrous interpretation that borders on the obscene.

But because all of these terms refer quite specifically to the trees, not to the male genitalia or sexual activity, and because there is nothing else in the poem to make the reader understand them to be metaphorical, the thinker who applies a sexual interpretation is quite simply guilty of reading into the poem that which is not in the poem but quite obviously is in the thinker’s mind.

Some beginning readers of poems believe that a poem always has to mean something other than what is stated. They mistakenly think that nothing in a poem can be taken literally, but everything must be a metaphor, symbol, or image that stands in place of something else. And they often strain credulity grasping at the unutterably false notion of a “hidden meaning” behind the poem.

That Unfortunate Reader Not Alone

Gregory is not the only uncritical thinker to be tricked by Frost’s “Birches.” Distinguished critic and professor emeritus of Brown University, George Monteiro, once scribbled: “To what sort of boyhood pleasure would the adult poet like to return? Quite simply; it is the pleasure of onanism.” Balderdash! The adult male remains completely capable of self-gratification; he need not engage boyhood memories to commit that act.

One is coaxed to advise Professor Monteiro—and all of those who fantasize self-gratification in “Birches”—to keep their minds above their waists while engaging in literary criticism and commentary.