Image: Stephen Vincent Benét

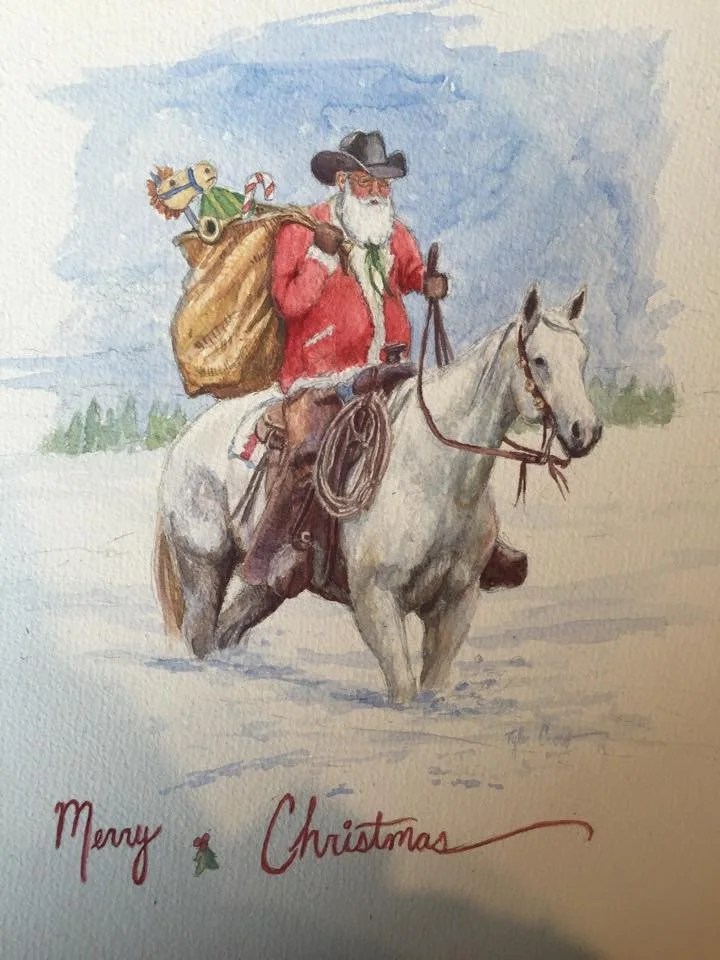

Stephen Vincent Benét’s “The Ballad of William Sycamore”

Not strictly a cowboy poem, Benét’s ballad, however, offers the mind-set of an individual close to the land, preferring the rural life to the urban.

Introduction and Text of “The Ballad of William Sycamore”

Stephen Vincent Benét’s “The Ballad of William Sycamore” features 19 rimed, stanzas of traditional ballad form. The subject is the rustic life of William Sycamore, narrated by Sycamore himself from just before his birth to after his death.

The Ballad of William Sycamore

My father, he was a mountaineer,

His fist was a knotty hammer;

He was quick on his feet as a running deer,

And he spoke with a Yankee stammer.

My mother, she was merry and brave,

And so she came to her labor,

With a tall green fir for her doctor grave

And a stream for her comforting neighbor.

And some are wrapped in the linen fine,

And some like a godling’s scion;

But I was cradled on twigs of pine

In the skin of a mountain lion.

And some remember a white, starched lap

And a ewer with silver handles;

But I remember a coonskin cap

And the smell of bayberry candles.

The cabin logs, with the bark still rough,

And my mother who laughed at trifles,

And the tall, lank visitors, brown as snuff,

With their long, straight squirrel-rifles.

I can hear them dance, like a foggy song,

Through the deepest one of my slumbers,

The fiddle squeaking the boots along

And my father calling the numbers.

The quick feet shaking the puncheon-floor,

And the fiddle squealing and squealing,

Till the dried herbs rattled above the door

And the dust went up to the ceiling.

There are children lucky from dawn till dusk,

But never a child so lucky!

For I cut my teeth on “Money Musk”

In the Bloody Ground of Kentucky!

When I grew as tall as the Indian corn,

My father had little to lend me,

But he gave me his great, old powder-horn

And his woodsman’s skill to befriend me.

With a leather shirt to cover my back,

And a redskin nose to unravel

Each forest sign, I carried my pack

As far as a scout could travel.

Till I lost my boyhood and found my wife,

A girl like a Salem clipper!

A woman straight as a hunting-knife

With eyes as bright as the Dipper!

We cleared our camp where the buffalo feed,

Unheard-of streams were our flagons;

And I sowed my sons like the apple-seed

On the trail of the Western wagons.

They were right, tight boys, never sulky or slow,

A fruitful, a goodly muster.

The eldest died at the Alamo.

The youngest fell with Custer.

The letter that told it burned my hand.

Yet we smiled and said, “So be it!”

But I could not live when they fenced the land,

For it broke my heart to see it.

I saddled a red, unbroken colt

And rode him into the day there;

And he threw me down like a thunderbolt

And rolled on me as I lay there.

The hunter’s whistle hummed in my ear

As the city-men tried to move me,

And I died in my boots like a pioneer

With the whole wide sky above me.

Now I lie in the heart of the fat, black soil,

Like the seed of the prairie-thistle;

It has washed my bones with honey and oil

And picked them clean as a whistle.

And my youth returns, like the rains of Spring,

And my sons, like the wild-geese flying;

And I lie and hear the meadow-lark sing

And have much content in my dying.

Go play with the towns you have built of blocks,

The towns where you would have bound me!

I sleep in my earth like a tired fox,

And my buffalo have found me.

Reading:

Commentary on “The Ballad of William Sycamore”

Speaking from two unlikely locales, William Sycamore narrates a fascinating tale of a fanciful life.

First Movement: Rough and Tumble Parents

The speaker describes his parents as scrappy, rough survivors. His mountaineer father had fists that resembled hammers; he ran as fast as a deer, and had a Yankee accent. His mother was merry and brave and also quite a tough woman, giving birth to the narrator under a tall green fir with no one to help her but “a stream for her comforting neighbor.”

While some folks can boast of clean linen fine to swaddle them, Sycamores cradle was a pile of pine twigs and he was wrapped in the skin of a mountain lion. Instead of “a starched lap / And a ewer with silver handles,” he recalls “a coonskin cap / And the smell of bayberry candles.”

Thus, Sycamore has set the scene of his nativity as rustic and rural, no modern conveniences to spoil him. He idealizes those attributes as he sees them making him strong and capable of surviving in a dangerous world.

Second Movement: Fun in the Cabin

Sycamore describes the cabin in which he grew up by focusing on the fun he saw the adults have when they played music and danced. Their visitors were tall, lank, “brown as snuff,” and they brought their long, straight squirrel rifles with them.

He focuses on the fiddle squealing and the dancing to a foggy song. The raucous partying was so intense that it rattled the herbs hanging over the door and caused a great cloud of dust to rise to the ceiling. He considers himself a lucky child to have experienced such, as well as being able to “cut [his] teeth on ‘Money Musk’ / In the Bloody Ground of Kentucky!”

Third Movement: Tall as Indian Corn

The speaker reports that he grew as tall as the Indian corn, and while his father had little to offer him in things, his father did give him a woodsman skill, which he found helpful. With his homespun gear, a leather shirt on his back, he was able to navigate the woodlands like a profession scout.

Fourth Movement: A Sturdy Wife

Reaching adulthood, Sycamore married a sturdy woman, whom he describes as “straight as a hunting-knife / With eyes as bright as the Dipper!” The couple built their home where the buffalo feed, where the streams had no names. They raised sons who were “right, tight boys, never sulky or slow.”

The oldest son died at the Alamo, and the youngest died with Custer. While the letters delivering the news of their fallen sons “burned [his] hand,” the grieving parents stoically said, “so be it!” and push ahead with their lives. What finally broke the speaker’s heart, however, was the fencing of his land, referring the government parceling land to individual owners.

Fifth Movement: Gutsy, Self-Reliance

The speaker still shows his gutsy, self-reliance in his breaking of a colt that bucked him off and rolled over him. After he recovered, however, he continues to hunt, and while the “city-men tried to move [him],” he refused to be influenced by any city ways. He died “in [his] boots like a pioneer / With the whole wide sky above [him].”

Sixth Movement: Speaking from Beyond

Speaking from beyond the grave somewhat like a Spoon River resident, only with more verve and no regret, William Sycamore describes his astral environment as a fairly heavenly place.

He is young again, reminding him of spring rain that returns every year, and his sons are free souls reminding him of wild geese in flight. He hears the meadow-lark, and he avers that he is very contented in his after-life state.

Sycamore disdained the city, as most rustics do, so he uses his final stanza to get in one last dig: “Go play with the town you have built of blocks.” He then insists that he would never be bound by a town, but instead he sleeps “in my earth like a tired fox, / And my buffalo have found me.” In his peaceful, afterlife existence, William Sycamore differs greatly from the typical Spoon River reporter.

image: Stephen Vincent Benét – Commemorative Stamp

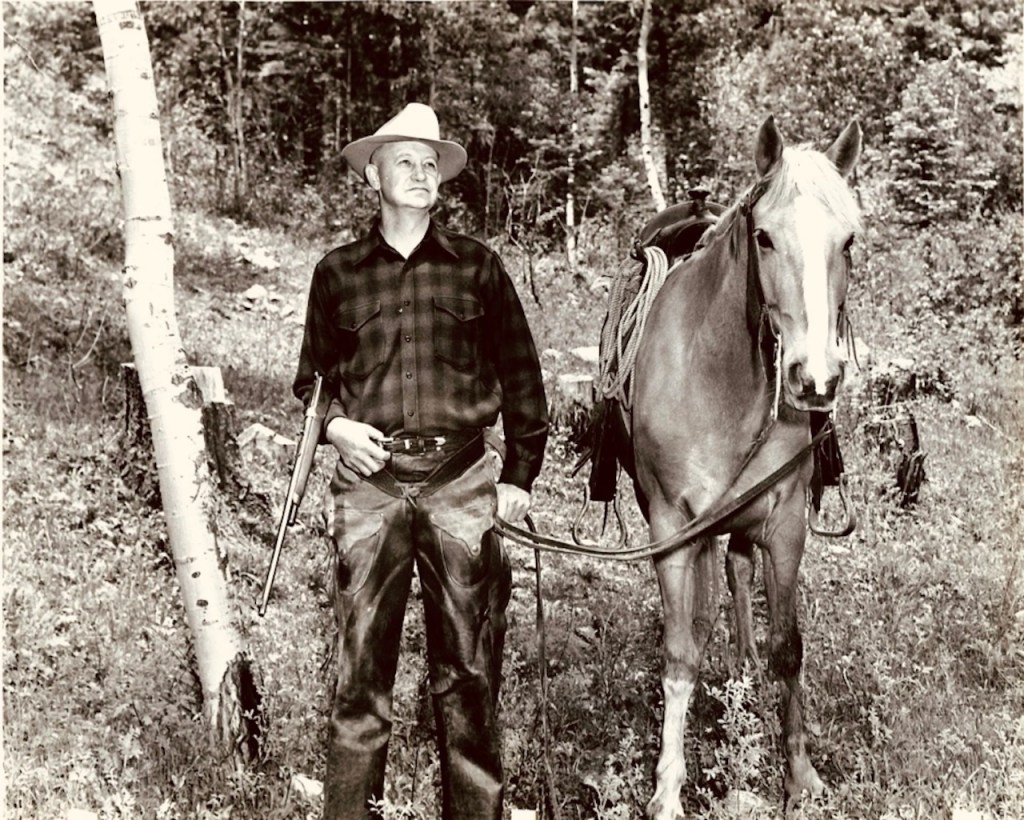

Brief Life Sketch of Stephen Vincent Benét

The works of Stephen Vincent Benét (1898–1943) [1] have influenced many other writers. Cowboy poet Joel Nelson claims that “The Ballad of William Sycamore” made him fall in love with poetry. Dee Brown’s title Bury my Heart at Wounded Knee comes directly from the final line of Benét’s poem titled “American Names” [2].

The book-length poem, John Brown’s Body, won him his first Pulitzer Prize in 1929 and remains the poet’s most famous work. Benét first published “The Ballad of William Sycamore” in the New Republic in 1922. Benét’s literary talent extended to other forms, including short fiction and novels. He also excelled in writing screenplays, librettos, an even radio broadcasts.

Born July 22, 1898, in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania [3] Benét graduated from Yale University in 1919 where instead of a typical thesis, he substituted his third collection of poems. His father was a military man who appreciated literary studies. His brother William and his sister Laura both became writers as well.

Benét’s first novel The Beginning of Wisdom was published in 1921, after which he relocated to France to study at the Sorbonne. He married the writer Rosemary Carr, and they returned to the USA in 1923, where his writing career blossomed.

The writer won the O. Henry Story Prize and a Roosevelt Medal, in addition to a second Pulitzer Prize, which was awarded posthumously in 1944 for Western Star. Just a week before spring of 1943, Benét succumbed to a heart attack in New York City; he was four month shy of his 45th birthday.

Sources

[1] Editors. “Stephen Vincent Benét.” Academy of American Poets. Accessed January 13, 2026.

[2] Darla Sue Dollman. “Buy My Heart at Wounded Knee and Stephen Vincent Benét.” Wild West History. October 4, 2013.

[3] Editors. “Stephen Vincent Benét.” Poetry Foundation. Accessed January 13, 2026.