Image: Robert Frost

Robert Frost’s “Carpe Diem”

The phrase “carpe diem” meaning “seize the day” originates with the classical Roman poet Horace. Frost’s speaker offers a different view that questions the usefulness of that idea. This poem offers a sample of the themes and the style in which Frost wrote most of his more successful poems.

Introduction with Text of “Carpe Diem”

The speaker in Robert Frost’s “Carpe Diem” offers a rebuttal to the philosophical advice portrayed in the notion “seize the day.” Frost’s speaker has decided that the present is not really that easy or valuable enough for capturing. Thus, this rebel has some subterfuge advice for his listeners. Let art and life coalesce on a new notion.

Carpe Diem

Age saw two quiet children

Go loving by at twilight,

He knew not whether homeward,

Or outward from the village,

Or (chimes were ringing) churchward,

He waited, (they were strangers)

Till they were out of hearing

To bid them both be happy.

“Be happy, happy, happy,

And seize the day of pleasure.”

The age-long theme is Age’s.

‘Twas Age imposed on poems

Their gather-roses burden

To warn against the danger

That overtaken lovers

From being overflooded

With happiness should have it.

And yet not know they have it.

But bid life seize the present?

It lives less in the present

Than in the future always,

And less in both together

Than in the past. The present

Is too much for the senses,

Too crowding, too confusing-

Too present to imagine.

Reading

Commentary on “Carpe Diem”

The phrase “carpe diem” meaning “seize the day” originates with the classical Roman poet Horace around 65 B. C. Frost’s speaker offers a different notion that questions the usefulness of that idea.

First Movement: Age as a Person

Age saw two quiet children

Go loving by at twilight,

He knew not whether homeward,

Or outward from the village,

Or (chimes were ringing) churchward,

He waited, (they were strangers)

Till they were out of hearing

To bid them both be happy.

“Be happy, happy, happy,

And seize the day of pleasure.”

In the first movement of Robert Frost’s “Carpe Diem,” the speaker creates a metaphor by personifying “Age,” who is observing a pair of young lovers. The lovers are on a journey—to where the speaker is not privy.

Because the speaker does not know exactly whither the couple is bound, he speculates that they may be simply going home, or may be traveling out of their home village, or they may be headed to church.

The last guess is quite possible because the speaker suggest that he is hearing the ringing of bells. Because the lovers are “strangers” to the speaker, he does not address them personally.

But after the couple can no longer hear, the speaker wishes for them happiness in their lives. He also adds the “carpe diem” admonition, elongating it to a full, “Be happy, happy, happy, / And seize the day of pleasure.”

Second Movement: A New Take on an Old Concept

The age-long theme is Age’s.

‘Twas Age imposed on poems

Their gather-roses burden

To warn against the danger

That overtaken lovers

From being overflooded

With happiness should have it.

And yet not know they have it.

At this point, after presenting a little drama exemplifying the oft touted employment of the expression in question, the speaker commences his evaluation of the age-old adage, “carpe diem.” The speaker first notes that is it always the old folks who foist this faulty notion upon the young.

This questionable command of the aged has spilled into poems the rose-gathering obligation related to time. His allusion to Robert Herrick’s “To the Virgins to Make Much of Time” will not be lost on the observant and the literary. The implication that a couple in love must stop with basking in that all-consuming feeling and take note of it is laughable to the speaker.

Lovers know they are in love, and they enjoy quite tangibly in the here-and-now that being in love. Telling them to “seize” that moment is like telling a toddler to stop and enjoy laughing as she enjoys playing with her toddler toys. One need not make a spectacle of one’s enjoyment for future use.

Third Movement: The Faulty Present

But bid life seize the present?

It lives less in the present

Than in the future always,

And less in both together

Than in the past. The present

Is too much for the senses,

Too crowding, too confusing-

Too present to imagine.

Lovers know they are in love and enjoy that state of being. They are, in fact, seizing the present with all their might. But for this speaker, the very idea of life in general being lived in the present only is faulty, cumbersome, and finally unattainable simply because of the way the human brain is naturally wired.

This speaker believes that life is lived “less in the present” than in the future. Folks always live and move with their future in mind. But surprisingly, according to this speaker, people live more in the past than in both the present and the future.

How can that be? Because the past has already happened. They have the specifics with which to deal. So the mind returns again and again to the past, as it merely contemplates the present and gives a nod to the future. Why not live more in the present? Because the present is filled with everything that attracts and stimulates the senses.

The senses, the mind, the heart, the brain become overloaded with all of the details that surround them. Those things crowd in on the mind and the present becomes “too present to imagine.”

The imagination plays such vital role in human life that the attempt to confine it to an area of overcrowding renders it too stunned to function. And the future: of course, the first complaint is that it has not happened yet. But the future is the fertile ground of the imagination.

Imagining what will come tomorrow is a popular way of spending time: What will we have for lunch? What job will I train for? Where will I live when I get married? What will my children look like?

These brain sparks all indicate future time. Thus the speaker has determined that the human mind lives more in the future than in the present. The “carpe diem” notion which this speaker has demoted to a mere suggestion remains a shining goal that is touted but few ever feel they can reach.

Maybe because they have not considered the efficacy of American poet Frost’s suggestion over the latinate command of Roman poet Horace, that notion will remain that shining yet seldom attained goal for mosts folks.

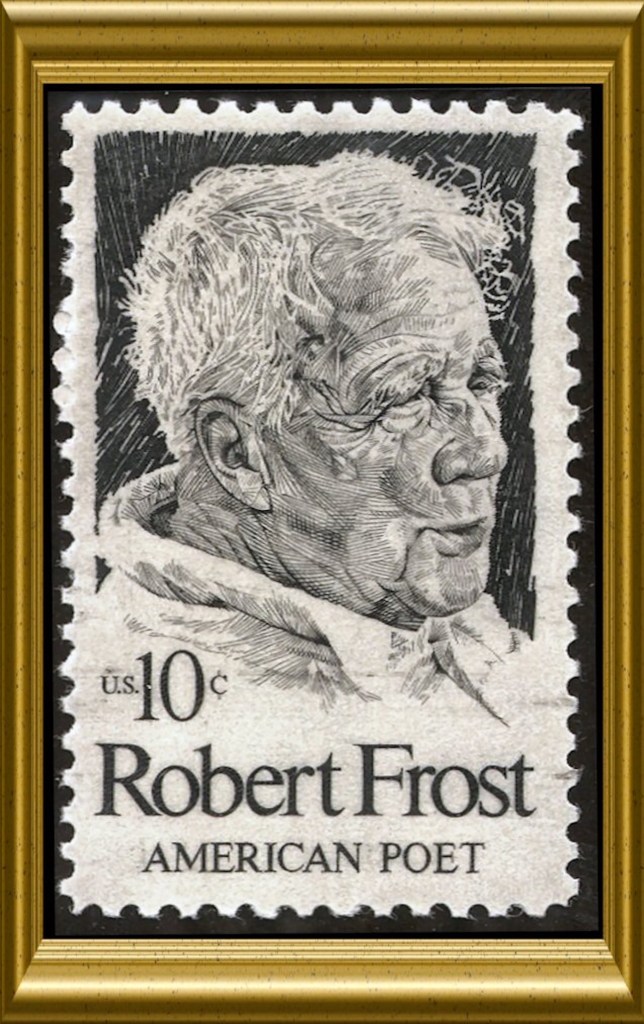

Robert Frost Commemorative Stamp – Linn’s Stamp News