Image: William Butler Yeats – Howard Coster – National Portrait Galley, London

William Butler Yeats’ “The Second Coming”

William Butler Yeats’ “The Second Coming” remains one of the most widely misunderstood poems of the 20th century. Many scholars and critics have failed to criticize the exaggeration in the first stanza and the absurd metaphor in the second stanza, which render a potentially fine poem a critical failure.

Introduction with Text of “The Second Coming”

Poems, in order to communicate, must be as logical as the purpose and content require. For example, if the poet wishes to comment on or criticize an issue, he must adhere to physical facts in his poetic drama. If the poet wishes to emote, equivocate, or demonstrate the chaotic nature of his cosmic thinking, he may legitimately do so without much seeming sense.

For example, Robert Bly’s lines—”Sometimes a man walks by a pond, and a hand / Reaches out and pulls him in” / / “The pond was lonely, or needed / Calcium, bones would do,”—are ludicrous [1] on every level. Even if one explicates the speaker’s personifying the pond, the lines remain absurd, at least in part because if a person needs calcium, grabbing the bones of another human being will not take care of that deficiency.

The absurdity of a lake needing “calcium” should be abundantly clear on its face. Nevertheless, the image of the lake grabbing a man may ultimately be accepted as the funny nonsense that it is. William Butler Yeats’ “The Second Coming” cannot be dismissed so easily; while the Yeats poem does not depict the universe as totally chaotic, it does bemoan that fact that events seem to be leading society to armageddon.

The absurdity surrounding the metaphor of the “rough beast” in the Yeats poem renders the musing on world events without practical substance.

The Second Coming

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

Commentary on “The Second Coming”

William Butler Yeats’ “The Second Coming” remains one of the most widely anthologized poems in world literature. Yet its hyperbole in the first stanza and ludicrous “rough beast” metaphor in the second stanza result in a blur of unworkable speculation.

First Stanza: Sorrowful over Chaos

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

The speaker is sorrowing over the chaos of world events that have left in their wake many dead people. Clashes of groups of ideologues have wreaked havoc, and much blood shed has smeared the tranquil lives of innocent people who wish to live quiet, productive lives.

The speaker likens the seemingly out of control situation of society to a falconer losing control of the falcon as he attempts to tame it. Everyday life has become chaotic as corrupt governments have spurred revolutions. Lack of respect for leadership has left a vacuum which is filled with force and violence.

The overstated claim that “The best lack all conviction, while the worst / Are full of passionate intensity” should have alerted the poet that he needed to rinse out the generic hyperbole in favor of more accuracy on the world stage.

Such a blanket, unqualified statement, especially in a poem, lacks the ring of truth: it simply cannot be true that the “best lack all conviction.” Surely, some the best still retain some level of conviction, or else improvement could never be expected.

It also cannot be true that all the worst are passionate; some of the worst are likely not passionate at all but remain sycophantic, indifferent followers. Any reader should be wary of such all-inclusive, absolutist statements in both prose and poetry.

Anytime a writer subsumes an entirety with the terms “all,” “none,” “everything,” “everyone,” “always,” or “never,” the reader should question the statement for its accuracy. All too often such terms are signals for stereotypes, which produce the same inaccuracy as groupthink.

Second Stanza: What Revelation?

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

The idea of “some revelation” leads the speaker to the mythological second coming of Christ. So he speculates on what a second coming might entail. However, instead of “Christ,” the speaker conjures the notion that an Egyptian-Sphinx-like character with ill-intent might arrive instead.

Therefore, in place of a second coming of godliness and virtue, as is the purpose of the original second coming, the speaker wonders: what if the actual second coming will be more like an Anti-Christ? What if all this chaos of bloodshed and disarray has been brought on by the opposite of Christian virtue?

Postmodern Absurdity and the “Rough Beast”

The “rough beast” in Yeats’ “The Second Coming” is an aberration of imagination, not a viable symbol for what Yeats’ speaker thought he was achieving in his critique of culture. If, as the postmodernists contend, there is no order [2] in the universe and nothing really makes any sense anyway, then it becomes perfectly fine to write nonsense.

Because this poet is a contemporary of modernism but not postmodernism [3], William Butler Yeats’ poetry and poetics do not quite devolve to the level of postmodern angst that blankets everything with the nonsensical. Yet, his manifesto titled A Vision is, undoubtedly, one of the contributing factors to that line of meretricious ideology.

Hazarding a Guess Can Be Hazardous

The first stanza of Yeats’ “The Second Coming” begins by metaphorically comparing a falconer losing control of the falcon to nations and governments losing control because of the current world disorder, in which “[t]hings fall apart; the centre cannot hold.”

Political factions employ these lines against their opposition during the time in which their opposition is in power, as they spew forth praise for their own order that somehow magically appears with their taking the seat of power.

The poem has been co-opted by the political class so often that Dorian Lynskey, overviewing the poem in his essay, “‘Things fall apart’: the Apocalyptic Appeal of WB Yeats’s The Second Coming,” writes, “There was apparently no geopolitical drama to which it could not be applied” [4].

The second stanza dramatizes the speaker’s musing about a revelation that has popped into his head, and he likens that revelation to the second coming of Christ; however, this time the coming, he speculates, may be something much different.

The speaker does not know what the second coming will herald, but he does not mind hazarding a dramatic guess about the possibility. Thus, he guesses that the entity of a new “second coming” would likely be something that resembles the Egyptian sphinx; it would not be the return of the Christ with the return of virtue but perhaps its opposite—vice.

The speaker concludes his guess with an allusion to the birth of such an entity as he likens the Blessed Virgin Mother to the “rough beast.” The Blessèd Virgin Mother, as a newfangled, postmodern creature, will be “slouching toward Bethlehem” because that is the location to which the first coming came.

The allusion to “Bethlehem” functions solely as a vague juxtaposition to the phrase “second coming” in hopes that the reader will make the connection that the first coming and the second coming may have something in common. The speaker speculates that at this very moment wherein the speaker is doing his speculation some “rough beast” might be pregnant with the creature of the “second coming.”

And as the time arrives for the creature to be born, the rough beast will go “slouching” towards its lair to give birth to this “second coming” creature: “its hour come round at last” refers to the rough beast being in labor.

The Flaw of Yeats’ “The Second Coming”

The speaker then poses the nonsensical question: “And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, / Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?” In order to make the case that the speaker wishes to make, these last two lines should be restructured in one of two ways:

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to give birth?

or

And what rough beast’s babe, its time come at last,

Is in transport to Bethlehem to be born?

An unborn being cannot “slouch” toward a destination. The pregnant mother of the unborn being can “slouch” toward a destination. But the speaker is not contemplating the nature of the rough beast’s mother; he is contemplating the nature of the rough beast itself.

The speaker does not suggest that the literal Sphinx will travel to Bethlehem. He is merely implying that a Sphinx-like creature might resemble the creature of the second coming. Once an individual has discounted the return of Jesus the Christ as a literal or even spiritual fact, one might offer personal speculation about just what a second coming would look like.

It is doubtful that anyone would argue that the poem is dramatizing a literal birth, rather than a spiritual or metaphorical one. It is also unreasonable to argue that the speaker of this poem—or Yeats for that matter—thought that the second coming actually referred to the Sphinx. A ridiculous image develops from the fabrication of the Sphinx moving toward Bethlehem. Yeats was more prudent than that.

Exaggerated Importance of Poem

William Butler Yeats composed a manifesto to display his worldview and poetics titled A Vision, in which he set down certain tenets of his thoughts on poetry, creativity, and world history. Although seemingly taken quite seriously by some Yeatsian scholars, A Vision is of little value in understanding either meaning in poetry or the meaning of the world, particularly in terms of historical events.

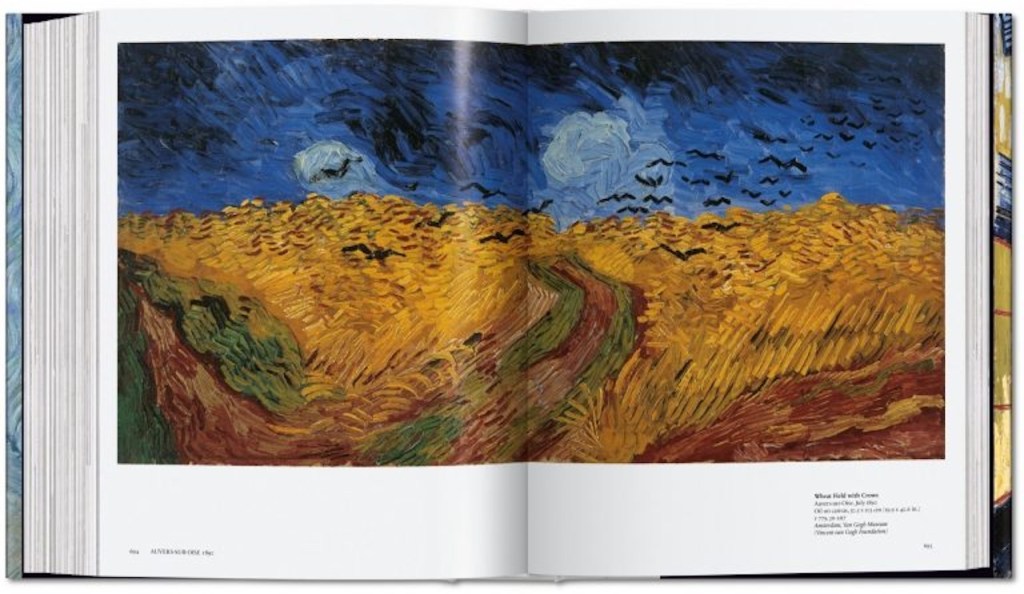

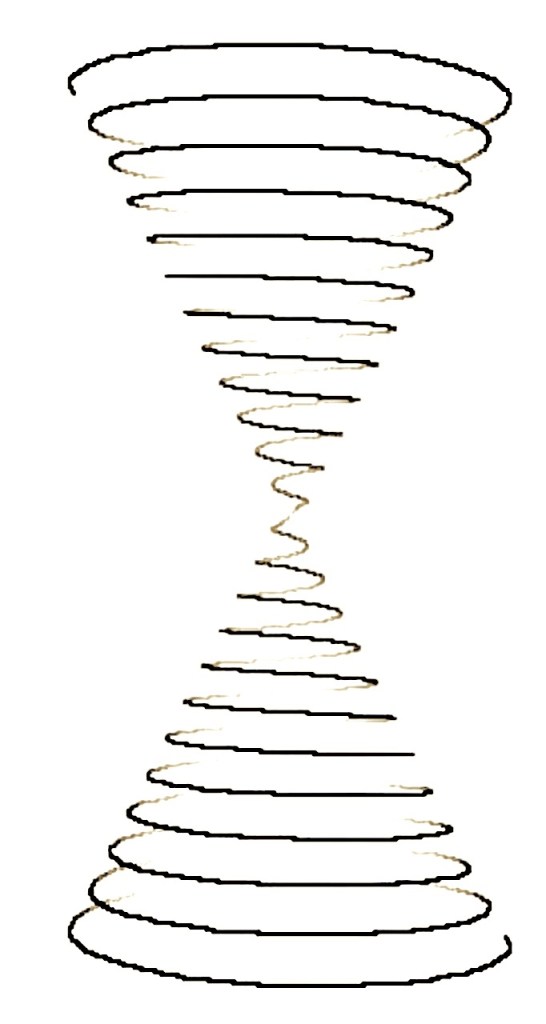

An important example of Yeats’ misunderstanding of world cycles is his explanation of the cyclical nature of history, exemplified with what he called “gyres” (pronounced with a hard “g.”) Two particular points in the Yeatsian explanation demonstrate the fallacy of his thinking:

- In his diagram, Yeats set the position of the gyres inaccurately; they should not be intersecting but instead one should rest one on top of the other: cycles shrink and enlarge in scope; they do not overlap, as they would have to do if the Yeatsian model were accurate.

Image : Gyres – Inaccurate Configuration from A Vision

Image: Gyres – Accurate Configuration

2. In the traditional Second Coming, Christ is figured to come again but as an adult, not as in infant as is implied in Yeats’ poem “The Second Coming.”

Of great significance in Yeats’ poem is the “rough beast,” apparently the Anti-Christ, who has not been born yet. And most problematic is that the rough beast is “slouch[ing] towards Bethlehem to be born.” The question is, how can such a creature be slouching if it has not yet been born? There is no indication the speaker wishes to attribute this second coming fiasco to the mother of the rough beast.

This illogical event is never mentioned by critics who seem to accept the slouching as a possible occurrence. On this score, it seems critics and scholars have lent the poem an unusually wide and encompassing poetic license.

The Accurate Meaning of the Second Coming

Paramahansa Yogananda has explained in depth the original, spiritual meaning of the phrase “the second coming”[5] which does not signify the literal coming again of Jesus the Christ, but the spiritual awakening of each individual soul to its Divine Nature through the Christ Consciousness.

Paramahansa Yogananda summarizes his two volume work The Second Coming of Christ: The Resurrection of the Christ Within You:

In titling this work The Second Coming of Christ, I am not referring to a literal return of Jesus to earth . . .

A thousand Christs sent to earth would not redeem its people unless they themselves become Christlike by purifying and expanding their individual consciousness to receive therein the second coming of the Christ Consciousness, as was manifested in Jesus . . .

Contact with this Consciousness, experienced in the ever new joy of meditation, will be the real second coming of Christ—and it will take place right in the devotee’s own consciousness. (my emphasis added)

Interestingly, knowledge of the meaning of that phrase “the second coming” as explained by Paramahansa Yogananda renders unnecessary the musings of Yeats’ poem “The Second Coming”and most other speculation about the subject. Still, the poem as an artifact of 20th century thinking remains an important object for study.

Sources

[1] Linda Sue Grimes. “Robert Bly’s ‘The Cat in the Kitchen’ and ‘Driving to Town Late to Mail a Letter’.” Linda’s Literary Home. December 24, 2025.

[2] David Solway. “The Origins of Postmodernitis.” PJ Media. March 25, 2011.

[3] Linda Sue Grimes. “Poetry and Politics under the Influence of Postmodernism.” Linda’s Literary Home. Accessed December 3, 2025.

[4] Dorian Lynsey. “‘Things fall apart’: the Apocalyptic Appeal of WB Yeats’s The Second Coming.” The Guardian. May 30, 2020.

[5] Editors. “The Truth Hidden in the Gospels. Self-Realization Fellowship. Accessed October 27, 2023.