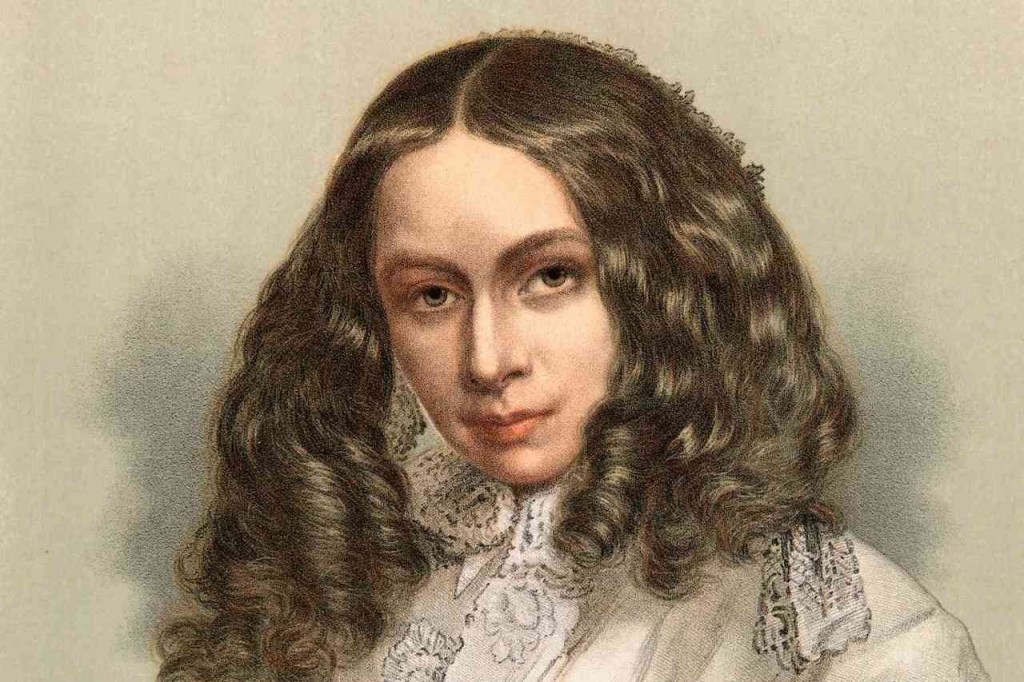

Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnet 4 “Thou hast thy calling to some palace-floor”

Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s sonnet 4 from Sonnets from the Portuguese continues with the speaker musing on her new relationship with her suitor, who seems too good to be true.

Introduction with Text of Sonnet 4 “Thou hast thy calling to some palace-floor”

The speaker in Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s sonnet 4 “Thou hast thy calling to some palace-floor” seems to be searching for a reason to believe that such a match with a suitor as distinguished as hers is even possible. She continues to brood in a melancholy line of thought, even as she seems to be becoming enthralled with the notion of having a true love in her life.

The speaker’s past continues to cause her to brood and remain skeptical, as she has difficulty accepting her own accomplishments and poetic talent. Likely, she is aware of her considerable ability, but when compared to her suitor, she feels that she cannot compete equally.

Sonnet 4 “Thou hast thy calling to some palace-floor”

Thou hast thy calling to some palace-floor,

Most gracious singer of high poems! where

The dancers will break footing, from the care

Of watching up thy pregnant lips for more.

And dost thou lift this house’s latch too poor

For hand of thine? and canst thou think and bear

To let thy music drop here unaware

In folds of golden fulness at my door?

Look up and see the casement broken in,

The bats and owlets builders in the roof!

My cricket chirps against thy mandolin.

Hush, call no echo up in further proof

Of desolation! there’s a voice within

That weeps … as thou must sing … alone, aloof.

Reading

Commentary on Sonnet 4 “Thou hast thy calling to some palace-floor”

Sonnet 4 marches on with the speaker’s musing on her new relationship with her suitor. She seems to remain skeptical that such a relationship can endure, even as she obviously hopes that it will.

She colorfully compares her lot with that of her suitor, by presenting an image of her dwelling juxtaposed with the image of the royal venue where her beloved is welcomed and where he performs.

First Quatrain: Mesmerizing Kings, Queens, and Royal Guests

Thou hast thy calling to some palace-floor,

Most gracious singer of high poems! where

The dancers will break footing, from the care

Of watching up thy pregnant lips for more.

In Sonnet 4 from Sonnets from the Portuguese, the speaker is addressing directly her suitor, as she continues her metaphorical comparison between the two lovers in a similar vain as she did with Sonnet 3. Once again, she takes note of her suitor’s invitations to perform for royalty, as she colorfully remarks, “Thou hast thy calling to some palace-floor.”

Her illustrious suitor has been a “[m]ost gracious singer of high poems,” and the royal guests curiously stop dancing to listen to him recite his poetry. The speaker visualizes her remarkable suitor at court, mesmerizing the king, queen, and royal guests with his poetic prowess.

Second Quatrain: Rhetorical Musings on Class Distinctions

And dost thou lift this house’s latch too poor

For hand of thine? and canst thou think and bear

To let thy music drop here unaware

In folds of golden fulness at my door?

In the second quatrain, the speaker puts forth a rhetorical question in two-parts:

1. Being one of such high breeding and accomplishment, are you sure that you want to visit one who is lower class than you?

2. Are you sure that you do not mind reciting your substantial and rich poetry in such a low class place with one who is not of your high station?

The questions remain rhetorical only in that the speaker entertains the deep hope that the answer to both parts of the question remains resoundingly in the affirmative. Because readers of this sequence already know how the drama turns out, they must wonder if as she was writing these melancholy thoughts, she secretly held the sentiment of relief, knowing that her skepticism and doubt had been laid to rest.

First Tercet: Contrasting Visual and Auditory Images

Look up and see the casement broken in,

The bats and owlets builders in the roof!

My cricket chirps against thy mandolin.

The speaker then insists that her royalty-worthy suitor take a good look at where she lives. The windows of her house are in disrepair, and she cannot afford to have “the bats and owlets” removed from the nests that they have built in the roof of her house. The final line of the first sestet offers a marvelous comparison that metaphorically states the difference between the suitor and speaker: “My cricket chirps against thy mandolin.”

On the literal level, she is only a plain woman living in a pastoral setting with simple possessions, while he is the opposite, cosmopolitan and richly endowed. And he is famous enough to be summoned by royalty, possessing the expensive musical instrument with which he can embellish his already distinguished art.

The lowly speaker’s “cricket” also metaphorically represent her own poems, which she likens to herself, poor creatures compared to the “high poems” and royal music of her illustrious suitor. The suitor’s “mandolin,” therefore, literally exemplifies wealth and leisure because it accompanies his poetry performance, and it figuratively serves as a counterpart to the lowly cricket of the speaker.

Second Tercet: A Natural Mode of Expression

Hush, call no echo up in further proof

Of desolation! there’s a voice within

That weeps … as thou must sing … alone, aloof.

The speaker again makes a gentle demand of her suitor, begging him, please do not be concerned or troubled for my rumblings about poverty and my lowly station. The speaker is asserting her belief that it is simply her natural mode of expression; her “voice within” is one that is given to melancholy, even as his voice is given to singing cheerfully.

The speaker implies that because she has lived “alone, aloof,” it is only natural that her voice would reveal her loneliness and thus contrast herself somewhat negatively with one as illustrious and accomplished as her suitor.

Good faith questions and comments welcome!